T cell exhaustion refers to a state of T cell dysfunction that develops during chronic infections and cancer. It is characterized by a progressive loss of effector functions, reduced proliferative capacity, and sustained expression of multiple inhibitory receptors[1,2,3]. This dysfunctional state poses a major obstacle to mounting effective immune responses against persistent pathogens and tumors, thereby limiting the efficacy of immunotherapies[2]. Notably, exhausted T cells (TEX) are distinct from anergic or senescent T cells, as they typically retain a certain level of responsiveness, particularly to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)[6].

This paper centers on T cell exhaustion (T cell fatigue), focusing on its association with the immune system, underlying mechanisms, and biomarkers. It further explores the role and mechanism of T cell exhaustion in chronic inflammation, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. Finally, it provides a review and commentary on the current research status and development prospects of this field.

Table of Contents

1. What is T cell exhaustion in immunology?

2. Mechanisms of T cell exhaustion

3. Biomarkers for T cell exhaustion

4. Role of T cell exhaustion in chronic infections

5. T cell exhaustion in cancer research

6. T cell exhaustion in autoimmune diseases

7. Recent advances in T cell exhaustion research

01 What is T cell exhaustion in immunology?

T cell exhaustion (T cell fatigue) is a crucial concept in immunological research, referring to a state that T cells gradually lose their functions under persistent antigen stimulation, such as in chronic infections or tumors[1,4]. This functional impairment is characterized by a progressive decline in T cell effector functions (e.g., cytokine production and cytotoxic capacity), impaired proliferative ability, and sustained high expression of multiple inhibitory receptors[2,4].

T cell exhaustion primarily occurs in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells that are continuously stimulated by chronic antigens. This phenomenon represents a "compromised" state of the organism when it fails to eliminate pathogens or tumors; it prevents tissue damage caused by excessive immune responses, while also leading to the dysfunction of the immune system. Understanding the mechanisms underlying T cell exhaustion is meaningful for the development of novel therapeutic strategies (such as immune checkpoint inhibitors) for treatment of chronic infectious diseases and cancer[1,4].

02 Mechanisms of T cell exhaustion

The mechanism underlying T cell exhaustion is complex, involving profound changes in the phenotype, function, metabolism, and epigenetic landscape of T cells.

Expression of inhibitory receptors: A prominent feature of exhausted T cells is the upregulation of multiple co-inhibitory receptors (also referred to as immune checkpoint molecules)[8,9]. These receptors include programmed death-1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule 3 (TIM-3), lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3), and T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT)[8,9]. Upon binding to their ligands, these inhibitory receptors negatively regulate T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production, thereby suppressing immune responses. PD-1 is typically expressed in the early stages of exhaustion, whereas TIM-3 and LAG-3 are more prominently expressed in the terminal exhausted state[8].

Functional impairment: Exhausted T cells exhibit a progressive loss of effector functions, including reduced secretion of cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-2 (IL-2); impaired cytotoxic activity; and decreased proliferative capacity[4]. This functional decline leds to immune evasion of pathogens and tumors[10].

Transcriptional and epigenetic remodeling: Core transcription factors (e.g., TOX, NR4A) establish and maintain the exhausted state upon activation of the calcineurin-NFAT pathway[11,12]. Meanwhile, persistent epigenetic modifications (such as histone modifications and DNA methylation) stabilize exhaustion-related gene expression profiles, ensuring their long-term stability. Additionally, modifications like m6A methylation of RNA regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level through corresponding protein complexes, collectively forming a complex regulatory network in exhausted T cells[11].

Metabolic dysfunction: Exhausted T cells undergo metabolic reprogramming, characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced metabolic adaptability[12]. While effector T cells typically rely on glycolysis for rapid energy production, exhausted T cells exhibit impaired glucose metabolism and mitochondrial respiratory function, processes critical for their function and survival. This metabolic shift limits their capacity to mount sustained immune responses. Recent studies have also identified that proteotoxic stress responses can drive T cell exhaustion and immune evasion[13].

Heterogeneity of Exhausted T Cells: T cell exhaustion (T cell fatigue) is not a single state but a functional continuum ranging from progenitor-like exhausted T cells (TPEX) to terminally exhausted T cells (TTEX)[14,15]. Among these subsets, TPEX cells retain proliferative capacity and are sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), making them critical for anti-tumor immunity. In contrast, TTEX cells exhibit severe functional impairment, which is difficult to reverse with current therapeutic strategies.This heterogeneity is supported by a well-defined molecular basis. For instance, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), SPRY1+ CD8+ T cells with progenitor-like characteristics have been identified as biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors and the prognosis of patients[15,16,17].

03 Biomarkers for T cell exhaustion

The identification of reliable biomarkers for T cell exhaustion or immunity exhaustion is essential for predicting patient outcomes, stratifying patients for ICI therapy, and monitoring treatment efficacy[18].

Markers of T cell exhaustion can be categorized into core markers, auxiliary markers, and function-related markers, with the common markers of these three categories summarized in the table below:

Table.1 T Cell Exhaustion Markers Classification[3,4,6,18]

|

Classification |

Biomarkers |

Core Characteristics & Functional Descriptions |

Application |

|

core markers |

PD-1(CD279) |

The most classic and specific marker, its expression level is positively correlated with the degree of exhaustion, and serves as the primary target of PD-1 inhibitors. |

One of the "gold standards" for defining the exhausted T cell population. It is expressed in almost all Tex cells. |

|

Tim-3 |

Co-expressed with PD-1, marking the entry of T cells into a state of severe exhaustion, at which point the functions of cell killing and cytokine secretion are nearly completely lost. |

A key indicator for determining the degree of exhaustion and is used to identify "terminally exhausted" T cell subsets. |

|

|

LAG-3 |

Forms the "core three markers" together with PD-1 and Tim-3, and directly inhibits T cell proliferation and the secretion of effector molecules. |

Combined detection can significantly improve the accuracy of identifying exhausted T cells, and it is an important research target for combined targets in immunotherapy. |

|

|

auxiliary markers |

TIGIT |

Highly expressed in exhausted T cells within the tumor microenvironment and synergistically enhances the immunosuppressive effect with PD-1. |

Subdivides tumor-associated exhausted T cell subsets and provides a basis for research on dual-target inhibitors (e.g., PD-1+TIGIT). |

|

CD39/CD73 |

Involved in adenosine metabolism, converting extracellular ATP into immunosuppressive adenosine, and indirectly reflects the state of T cell functional suppression. |

Assists in determining the intensity of the immunosuppressive microenvironment where T cells reside and is commonly used in tumor microenvironment analysis. |

|

|

CTLA-4 |

Expressed in early-stage exhausted T cells or some of their subsets, inhibits T cell activation, and has lower specificity than PD-1. |

Suitable for studying the early differentiation process of exhausted T cells and also serves as the target of CTLA-4 inhibitors. |

|

|

function-related markers |

IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 |

Effector cytokines, its secretion by exhausted T cells. Its’,decrease directly reflecting the degree of impairment in cellular function. |

Validates T cell exhaustion at the functional level and compensates for the limitations of judgment based solely on surface molecules. |

|

T-bet, Eomes |

Transcription factors that regulate T cell differentiation. In the exhausted state, T-bet expression is decreased while Eomes expression is increased. |

It explains the differentiation direction of T cell exhaustion at the molecular mechanism level and is used in mechanistic research. |

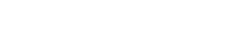

Fig. 1 Human peripheral blood lymphocytes were stained with 0.2 μg Purified Anti-Human CD279 Antibody[EH12.2H7] (Right) and 0.2 μg Mouse IgG1, κ Isotype Control (Left), followed by Elab Fluor® 647-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody, then anti-Human CD3 PE-conjugated Monoclonal Antibody.

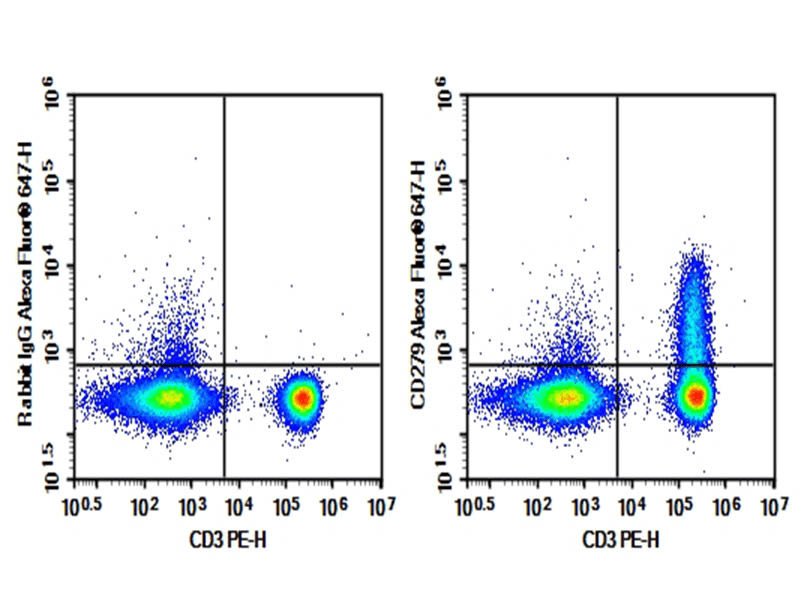

Fig. 2 Human peripheral blood lymphocytes were activated for 3 days with PHA, then stained with 0.2 μg AF/LE Purified Anti-Human CD274/PD-L1 Antibody[29E.2A3] (Right) and 0.2 μg Mouse IgG2b, κ Isotype Control (Left), followed by Elab Fluor® 647-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody, then anti-Human CD3 PE-conjugated Monoclonal Antibody.

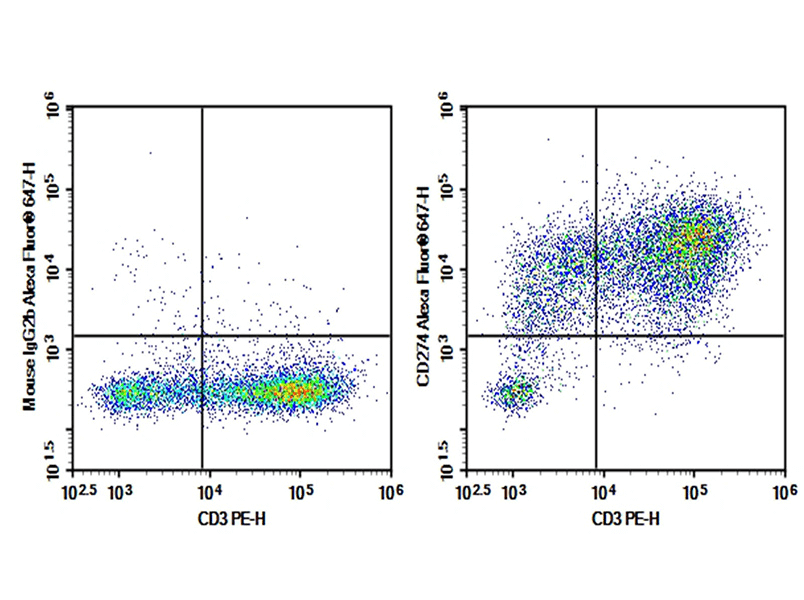

Fig. 3 C57BL/6 mouse splenocytes were stained with APC Anti-Mouse CD4, FITC Anti-Mouse CD366, FITC Anti-Mouse CD279/PD-1, followed by analysise via flow cytometry.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table.2 Multicolor Panel for Flow Cytometric Analysis of T Exhaustion

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Species Reactivity |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Human |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1230S |

Human |

|

CD4 |

SK3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1352C |

Human |

|

CD8 |

OKT-8 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1110J |

Human |

|

CD25 |

BC96 |

PE |

E-AB-F1194D |

Human |

|

CD279/PD-1 |

EH12.2H7 |

/ |

E-AB-F12290 |

Human |

|

CD274/PD-L1 |

29E.2A3 |

/ |

E-AB-F11330 |

Human |

|

CD4 |

GK1.5 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1097S |

Mouse |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1136Q |

Mouse |

|

CD3 |

17A2 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1013C |

Mouse |

|

CD8a |

53-6.7 |

PerCP |

E-AB-F1104F |

Mouse |

|

CD336/Tim-3 |

RMT3-23 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1192C |

Mouse |

|

CD279/PD-1 |

29F.1A12 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1131C |

Mouse |

04 Role of T cell exhaustion in chronic infections

T cell exhaustion represents a critical immunopathological process in chronic infections. In chronic infections (e.g., HIV, HBV, HCV, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections), the persistent presence of pathogens leads to prolonged antigenic stimulation of antigen-specific T cells (predominantly CD8+T cells, with involvement of CD4+T cells), which gradually enter a state of exhaustion[1,4,6,8].

Characteristics of this state include: sustained high expression of immune checkpoint molecules (such as PD-1, Tim-3, and LAG-3); a significant reduction in the capacity to secrete cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α); impaired proliferative capacity and cytotoxic function; and remodeling of transcriptional regulatory networks (e.g., decreased T-bet expression and increased Eomes expression)[6,8].

T cell exhaustion in chronic infections markedly impairs the body's ability to clear pathogens, resulting in persistent or progressive infection, while also increasing the risk of secondary infections or immune-related complications. Therefore, in-depth elucidation of the regulatory mechanisms underlying T cell exhaustion in chronic infections and exploration of strategies to reverse exhaustion (such as the application of immune checkpoint inhibitors) are of great significance for improving clinical outcomes in chronic infections.

05 T cell exhaustion in cancer research

T cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment: T cell exhaustion (T cell fatigue) is a core concept in the field of tumor immunology. It refers to a state of T cell functional inactivation in the tumor microenvironment (TME), where T cells gradually lose effector functions and proliferative capacity due to long-term exposure to persistent antigens and immunosuppressive signals, accompanied by stably high expression of multiple inhibitory receptors (e.g., PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3)[19,20]. In addition to the intrinsic mechanisms mentioned above, the tumor microenvironment also plays a critical role in driving T cell exhaustion. The TME is a highly immunosuppressive and complex ecosystem, consisting of immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), as well as various immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10) and metabolites. These components act synergistically to inhibit T cell activation and function, ultimately promoting the establishment and maintenance of their exhausted state[6,19,20].

T cell exhaustion represents one of the key mechanisms by which tumors achieve immune evasion, exerting a significant impact on cancer therapy. Exhausted T cells exhibit impaired functionality and fail to effectively recognize and eliminate tumor cells, thereby promoting tumor growth, progression, and metastasis[19,20]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that T cell exhaustion is closely associated with poor patient prognosis in various malignant tumors[19,20].

At the therapeutic level, T cell exhaustion also constitutes a core factor limiting the efficacy of immunotherapy. Although immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapies (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies) can reverse T cell exhaustion and achieve remarkable therapeutic effects in some patients, their overall clinical application still faces multiple challenges, such as limited response rates, primary or secondary resistance, and immune-related adverse events. Furthermore, there is substantial heterogeneity within the exhausted T cell population: progenitor-like exhausted T cells are relatively sensitive to ICB therapy, whereas terminally exhausted T cells show almost no response. This discrepancy further impacts the overall therapeutic outcome[19,20].

06 T cell exhaustion in autoimmune diseases

The emerging research indicates a complex and nuanced role for T cell exhaustion in autoimmune diseases, presenting both potential therapeutic opportunities and challenges.

The mechanisms driving T cell exhaustion are multifaceted and closely linked to their role in autoimmune disorders. First, persistent antigen stimulation, where self-antigens in autoimmune diseases act as chronic triggers, analogous to viral antigens in chronic infections or tumor antigens in cancer, drives autoreactive T cells into a dysfunctional state, though some cases (e.g., chronic HBV infection) involve T cell dysfunction deviating from classic exhaustion models (PD1 T cell exhaustion or CD8 T cell exhaustion ). Second, sustained upregulation of co-inhibitory receptors is a hallmark: PD-1 and CTLA-4 prevent T cell overactivation to regulate autoimmunity (while their blockade exacerbates autoimmunity), and TIM-3/LAG-3 often co-express with PD-1 to indicate more severe exhaustion, collectively impairing T cell function[1,4,6,12]. Third, metabolic dysfunction, characterized by mitochondrial impairment, altered glucose metabolism and respiration, and (in aging) reduced autophagy (critical for cellular quality control), limits T cell metabolic fitness and effector function maintenance. Fourth, profound epigenetic remodeling, including histone modifications, chromatin accessibility changes, DNA methylation, and dysregulation of transcription factors (e.g., TOX as a master regulator, plus NFAT, NR4A, Eomes), stably establishes and maintains the exhausted phenotype while preventing T cell reinvigoration. Finally, the inflammatory microenvironment plays a key role: immunosuppressive cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10) sustain exhaustion by inhibiting T cell activation, whereas IL-2 promotes T cell proliferation and survival.

The role of T cell exhaustion in autoimmune diseases is paradoxical, with both beneficial and detrimental implications. On one hand, it may exert a protective effect via "therapeutic exhaustion": in certain autoimmune settings (e.g., type 1 diabetes, where CD8+ T cell exhaustion degree is under investigation), suppressing overactive autoreactive T cells to mitigate tissue damage, which serves as a natural mechanism against uncontrolled self-reactive immune responses[4,6,12]. On the other hand, dysregulated development or maintenance of T cell exhaustion can impair immune tolerance. For instance, IgG immune complexes breaking human microglia tolerance (contributing to neuroinflammatory autoimmune diseases) or unregulated innate and adaptive immunity in systemic autoimmune diseases can enable pathogenic autoreactive T cells to escape control and drive disease progression. Additionally, T cell expression of inhibitory receptors (e.g., PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, LAG-3), together with transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic profiles, holds potential as biomarkers for disease activity, prognosis, or therapeutic response in autoimmune conditions[3,4,6,21].

07 Recent advances in T cell exhaustion research

Recent advances in T cell exhaustion research have illuminated the intricate mechanisms driving this dysfunctional state and revealed promising therapeutic strategies to restore T cell function and enhance anti-tumor immunity[22].

Given T cell exhaustion’s central role in immunotherapy resistance, extensive research focuses on reversing this state via multiple strategies. First, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) advances beyond PD-1/CTLA-4, with novel targets (e.g., PSGL-1 in melanoma and B-cell lymphoma, STS2/UBASH3A, PTGIR, ADRB1, BATF2-RGS2 axis, MIF) and mathematical models exploring ICI efficacy across exhaustion states[4,6,24]. Second, metabolic reprogramming targets mitochondria (enhancing oxidative phosphorylation, improving adaptation, reversing depolarization) to restore T cell function, as mitochondrial metabolism governs T cell fate. Third, epigenetic modulation addresses barriers to terminally exhausted T cell rejuvenation, with chromatin profiling and machine learning identifying synthetic promoters for therapeutic intervention. Fourth, gene engineering and cell therapies include gene-edited exosomes, CRISPR-optimized CAR-T cells (e.g., PD-1 disruption), and overcoming CAR-T exhaustion[24,26]. Fifth, tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation targets immunosuppressive components (MDSCs, TAMs, CAFs) or pathways (cGAS-STING) to reduce exhaustion, alongside lncRNA targets (e.g., AL031775.1 in osteosarcoma). Sixth, strategies address intertwined T cell senescence and aging, leveraging epigenetic regulation to improve immunotherapy outcomes[23]. Finally, emerging approaches involve nanowires for miRNA-driven exhaustion control and small molecules (e.g., Tanshinone I) for T cell immunomodulation[24,25,26].

The field of T cell exhaustion research (T cell fatigue) is rapidly evolving, with significant advances in understanding its molecular underpinnings and developing innovative strategies to restore T cell function[25,26]. These approaches range from novel immune checkpoint targets and epigenetic modulators to metabolic reprogramming and advanced gene-editing techniques, all aimed at enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies against cancer and chronic infections.

References:

[1] Saeidi, A., Zandi, K., Cheok, Y. Y., Saeidi, H., Wong, W. F., Lee, C. Y. Q., Cheong, H. C., Yong, Y. K., Larsson, M., & Shankar, E. M. (2018). T-Cell Exhaustion in Chronic Infections: Reversing the State of Exhaustion and Reinvigorating Optimal Protective Immune Responses. Frontiers in Immunology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02569.

[2] Wherry, E. J., & Kurachi, M. (2015). Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nature Reviews Immunology, 15(8), 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3862.

[3] Wherry, E. J. (2013). Molecular Basis of T-Cell Exhaustion. Blood, 122(21), SCI-38-SCI-38. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v122.21.sci-38.sci-38.

[4] Kurachi, M. (2019). CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Seminars in Immunopathology, 41(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-019-00744-5.

[5] Jin, H.-T., Jeong, Y.-H., Park, H.-J., & Ha, S.-J. (2011). Mechanism of T cell exhaustion in a chronic environment. BMB Reports, 44(4), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2011.44.4.217.

[6] Baessler, A., & Vignali, D. A. A. (2024). T Cell Exhaustion. Annual Review of Immunology, 42(1), 179–206. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-090222-110914.

[7] Wang, J., Xu, Y., Huang, Z., & Lu, X. (2018). T cell exhaustion in cancer: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 119(6), 4279–4286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26645.

[8] Wherry, E. J., & Kurachi, M. (2015). Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nature Reviews Immunology, 15(8), 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3862.

[9] Okoye, I. S., Houghton, M., Tyrrell, L., Barakat, K., & Elahi, S. (2017). Coinhibitory Receptor Expression and Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Maintaining a Balance in CD8+ T Cell Responses to Chronic Viral Infections and Cancer. Frontiers in Immunology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01215.

[10] Wang, J., Xu, Y., Huang, Z., & Lu, X. (2018). T cell exhaustion in cancer: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 119(6), 4279–4286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26645.

[11] Zhu, Y., Tan, H., Wang, J., Zhuang, H., Zhao, H., & Lu, X. (2024). Molecular insight into T cell exhaustion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmacological Research, 203, 107161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107161.

[12] Zu, H., & Chen, X. (2024). Epigenetics behind CD8+ T cell activation and exhaustion. Genes & Immunity, 25(6), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-024-00307-1.

[13] Wang, Y., Ma, A., Song, N.-J., Shannon, A. E., Amankwah, Y. S., Chen, X., Wu, W., Wang, Z., Saadey, A. A., Yousif, A., Ghosh, G., Mandula, J. K., Velegraki, M., Xiao, T., Wen, H., Huang, S. C.-C., Wang, R., Beusch, C. M., Dawood, A. S., … Li, Z. (2025). Proteotoxic stress response drives T cell exhaustion and immune evasion. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09539-1.

[14] Liu, X., & Peng, G. (2021). Mitochondria orchestrate T cell fate and function. Nature Immunology, 22(3), 276–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-020-00861-6.

[15] Blank, C. U., Haining, W. N., Held, W., Hogan, P. G., Kallies, A., Lugli, E., Lynn, R. C., Philip, M., Rao, A., Restifo, N. P., Schietinger, A., Schumacher, T. N., Schwartzberg, P. L., Sharpe, A. H., Speiser, D. E., Wherry, E. J., Youngblood, B. A., & Zehn, D. (2019). Defining ‘T cell exhaustion.’ Nature Reviews Immunology, 19(11), 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0221-9.

[16] Gonzalez, N. M., Zou, D., Gu, A., & Chen, W. (2021). Schrödinger’s T Cells: Molecular Insights Into Stemness and Exhaustion. Frontiers in Immunology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.725618.

[17] Admasu, T. D., & Yu, J. S. (2025). Harnessing Immune Rejuvenation: Advances in Overcoming T Cell Senescence and Exhaustion in Cancer Immunotherapy. Aging Cell, 24(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.70055.

[18] Coschi, C. H., & Juergens, R. A. (2023). Overcoming Resistance Mechanisms to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Leveraging the Anti-Tumor Immune Response. Current Oncology, 31(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31010001.

[19] Kang, K., Lin, X., Chen, P., Liu, H., Liu, F., Xiong, W., Li, G., Yi, M., Li, X., Wang, H., & Xiang, B. (2024). T cell exhaustion in human cancers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, 1879(5), 189162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2024.189162.

[20] Wang, J., Xu, Y., Huang, Z., & Lu, X. (2018). T cell exhaustion in cancer: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 119(6), 4279–4286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26645.

[21] He, X.-S., Gershwin, M. E., & Ansari, A. A. (2017). Checkpoint-based immunotherapy for autoimmune diseases – Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Autoimmunity, 79, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2017.02.004.

[22] Li, C., Yuan, Y., Jiang, X., & Wang, Q. (2025). Epigenetic regulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion: recent advances and update. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1700039.

[23] Li, G., Li, D., & Zhu, X. (2025). Next-generation T cell immunotherapy: overcoming exhaustion, senescence, and suppression. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1662145.

[24] Zu, H., & Chen, X. (2024). Epigenetics behind CD8+ T cell activation and exhaustion. Genes & Immunity, 25(6), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-024-00307-1.

[25] Lei, T., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Cao, J., Huang, J., Chen, J., Chen, H., Zhang, J., Wang, L., Xu, X., Gale, R. P., & Wang, L. (2024). Leveraging CRISPR gene editing technology to optimize the efficacy, safety and accessibility of CAR T-cell therapy. Leukemia, 38(12), 2517–2543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02444-y.

[26] Zhang, H., Gao, J., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, B. (2025). Current status of chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy and its exhaustion mechanism. Immunotherapy, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750743x.2025.2560798.