The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their groundbreaking discoveries on regulatory T cells (Tregs) and the FOXP3 gene, which have revolutionized our understanding of immune regulation and opened new frontiers in treating autoimmune diseases, cancer, and transplant rejection.

This article offers a comprehensive overview of regulatory T cells (Tregs), and the mechanistic role of FOXP3 in regulating the development and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs). Furthermore, introduces detection tools for FOXP3 and Tregs, explores the applications and future directions of Treg cells in health and disease , and sheds light on emerging clinical applications stemming from these discoveries.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: The 2025 Nobel Prize and the Discovery of Treg Cells

2. The Central Role of FOXP3 in Regulatory T Cell Function

3. Advancing Immunology Research: Detection Tools for FOXP3 and Treg

4. Treg Cells in Health and Disease

5. Applications and Future Directions

6. Conclusion: From Nobel Discovery to Research Innovation

01 Introduction: The 2025 Nobel Prize and the Discovery of Treg Cells

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists for their groundbreaking revelations concerning how regulatory T cells (Treg cells) prevent autoimmune diseases[1]. This recognition highlights the critical role of Treg cells in maintaining immune homeostasis and modulating immune responses to prevent pathologies[2].

Treg cells, a suppressive subset of CD4+ T cells, are integral to preventing multi-system autoimmunity by regulating excessive immune responses[3,4]. The discovery of Treg cells can be divided into three key stages:

1995: Identification of Regulatory T Cells by Shimon Sakaguchi

In a pivotal study, Japanese scientist Shimon Sakaguchi demonstrated that surgical removal of a specific T cell subset, characterized by the surface markers CD4⁺CD25⁺, from mice resulted in the development of severe autoimmune pathologies, including colitis and lupus erythematosus. Conversely, adoptive transfer of these cells back into the animals reversed the autoimmune manifestations. This work provided the first functional evidence that a dedicated lymphocyte population exists to actively suppress excessive immune responses, which Sakaguchi termed regulatory T cells (Tregs). His findings contested the then-dominant paradigm that immune tolerance was achieved solely through central thymic selection, thereby establishing a foundational concept for subsequent immunological research[5].

2001: Discovery of FOXP3 as a Master Regulator by Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell

American researchers Mary E. Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell investigated the molecular basis of IPEX syndrome (Immune Dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked), a severe human autoimmune disorder. They identified mutations in the FOXP3 gene as the causative defect in IPEX patients and showed that these mutations led to a profound loss or functional impairment of Tregs. Subsequent analysis confirmed FOXP3 as a specific molecular marker of Treg identity, indicating that its expression is necessary for the immunosuppressive function of these cells. This discovery linked Treg biology to a definitive genetic locus, clarifying their molecular identity[6,7,8].

2003: Functional Validation of FOXP3 in Treg Lineage Specification

In follow-up genetic engineering experiments, Brunkow and Ramsdell ectopically expressed the FOXP3 gene in conventional T cells and observed that these cells acquired a suppressive phenotype and functional characteristics of Tregs. This gain-of-function experiment conclusively established FOXP3 as the master regulatory transcription factor controlling Treg differentiation and function. Its normal expression proved critical for the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Collectively, these studies elucidated the identity, function, and mechanistic basis of Tregs, elevating their understanding from a phenomenological observation to a tractable mechanistic paradigm[9].

Discovered three decades ago, the therapeutic promise of harnessing Treg cells has strengthened considerably, with multiple clinical trials exploring strategies to enhance endogenous Treg cells or deliver them as cell-based therapies[3]. The Nobel Prize announcement underscores the scientific community's recognition of the profound impact of understanding Treg cell biology for treating various diseases, including autoimmune conditions, transplant rejection, and certain cancers[1,3].

02 The Central Role of FOXP3 in Regulatory T Cell Function

The Forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) transcription factor is central and indispensable for the development, maintenance, and suppressive function of regulatory T cells (Tregs), a specialized T lymphocyte subset critical for immune homeostasis, autoimmunity prevention, and the regulation of immune responses to infections, allergies, and cancer. Mutations in the FOXP3 gene cause the severe autoimmune disorder,for example Immune Dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, underscoring its key role in immune tolerance[9,10,11].

As a master regulator, FOXP3 orchestrates the transcriptional program governing Treg lineage specification and function. It directly or indirectly regulates genes involved in Treg development, stability, and suppressive activity (e.g., CTLA-4, IL-2 receptor alpha)[9,10]. While FOXP3 expression is largely restricted to αβ T cells and correlates with suppressor activity, it alone does not always confer a Treg phenotype, reflecting the complexity of Treg identity[11].

FOXP3’s function in Tregs relies on cooperation with other transcription factors, most notably Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells (NFAT). Upon antigen stimulation, NFAT (activated by calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation) forms complexes with FOXP3 (instead of AP-1 in conventional T cells) to drive Treg-specific gene expression[12]. Calcineurin also enables NFAT to interact with Smad3, binding the FOXP3 conserved non-coding sequence 1 (CNS1) to initiate FOXP3 transcription[12].

FOXP3 stability and activity are tightly regulated via post-translational modifications (e.g., O-GlcNAcylation, phosphorylation by NLK/TAK1) and interactions with cellular machinery[13]. Physiological stimuli (TCR signaling, IL-2, pro-inflammatory cytokines) dynamically adjust its transcriptional output, while FOXP3 gene enhancers and Forkhead-domain proteins (FOXP1/FOXP4) support Treg suppressive capacity[14].

FOXP3+Tregs exhibit heterogeneity across human pathologies (autoimmunity, cancer), inflammatory conditions can reduce their stability or convert them to pathogenic effector cells, complicating therapeutic use. However, supraphysiological FOXP3 expression improves CAR-Treg efficacy and safety, and immune checkpoint molecules (LAG-3, TIM-3, PD-1) on FOXP3-CAR-nTregs show promise for engineered T-cell therapies[10,15].

Mechanisms controlling FOXP3 expression are multifaceted: the Treg-specific demethylated site (TSDR) contains a CREB binding site (CREB modulates FOXP3 function and IL-10 production); metabolic programs and nutrient signaling tune FOXP3+ Treg function; epigenetic regulation (H3K27me3,p53, DNMT1-mediated methylation) maintains Treg identity and balances Treg/Th17 lineages; and lncRNAs (SNHG1, CRNDE) regulate Th17/Treg imbalance in diseases like diabetic kidney disease[16,17,18,19].

Beyond Tregs, FOXP3 influences other immune cells: it enhances MHC Class I transcription in T cells (elevating levels in CD4+CD25+ Tregs vs. conventional CD4+CD25- T cells) and regulates humoral immunity by suppressing B cell activation, proliferation, and class-switch recombination (directly or via T-helper cells). It is also expressed in myeloid cell subsets, indicating a broader immune role[19,20].

In disease contexts, FOXP3/Treg regulation is critical: vitamin D analogues (e.g., calcipotriol) control psoriasis-like dermatitis via T cells; VEGF-A from CD4+ T and myeloid cells disrupts corneal nerves in herpes stromal keratitis; and Treg imbalance (potentially linked to FOXP3 mutations) may contribute to migraine. Compounds like rubiginosin B (targeting calcineurin-NFAT signaling) inhibit Treg differentiation to enhance anti-tumor immunity, while Huangqi-Guizhi-Wuwu Decoction (HGWD) modulates CD4+ T cell differentiation (via JAK-STAT signaling) to prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Additionally, hydrophobic secondary bile acids influence Treg differentiation via FOXP3 and NR4A1[21,22].

Emerging research identifies new regulators of FOXP3/Treg function: ATM (a DNA damage response protein) may impact Treg development; cGAS-CTCF maintains Treg development; and the actin remodeling protein Flightless-1 is essential for Treg function. These findings highlight the intricate molecular network governing FOXP3-mediated immune regulation and its profound implications for health and disease[23,24].

In summary, FOXP3 sits at the center of a complex regulatory network that directs Tcell lineage commitment, functional specialization, and systemic immune balance. Its critical role continues to inspire therapeutic innovations aimed at modulating immune tolerance in autoimmunity, cancer, and inflammatory diseases.

03 Advancing Immunology Research: Detection Tools for FOXP3 and Tregs

In immunological research, detection tools for Forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) and Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a crucial role in gaining in-depth insights into immune homeostasis, autoimmune diseases, and tumor immunity. FOXP3 is the core transcription factor of Tregs, and its expression is essential for the suppressive function and lineage maintenance of Tregs. Therefore, effective detection methods can not only help researchers identify and quantify Tregs but also evaluate their functional status.

FOXP3 Detection Methods

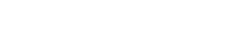

The identification and analysis of FOXP3, a key intracellular transcription factor defining regulatory T cells (Tregs), rely on several well-established techniques. Flow cytometry remains the most widely used approach, enabling simultaneous detection of surface markers (CD4, CD25) and intracellular FOXP3 at single-cell resolution, thereby allowing precise quantification of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+Tregs and their subsets, although the requirement for cell fixation and permeabilization complicates the procedure[8,26,27]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) provides spatial context by visualizing FOXP3+ Tregs within tissue sections, making it invaluable for assessing Treg infiltration in tumor or autoimmune microenvironments[10,25,26,27]. RT-qPCR measures FOXP3 mRNA expression, offering insights into transcriptional regulation under various conditions, albeit without protein-level or single-cell resolution. In contrast, Western Blot detects total FOXP3 protein in bulk lysates but lacks cellular specificity. Together, these methods form a complementary toolkit for Treg research, each contributing distinct insights into FOXP3 expression and Treg biology[10,25,26,27].

Fig. 1 C57BL/6 mouse splenocytes were surface stained with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Mouse CD45, PE/Cyanine7 Anti-Mouse CD45R/B220, FITC Anti-Mouse CD3, Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Mouse CD4, PerCP Anti-Mouse CD8a and APC Anti-Mouse CD25 and then treated with Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit.Cells were then stained with PE Anti-Mouse Foxp3, followed by analysise via flow cytometry. Regulatory T cells(Treg cells) exhibit the phenotype of CD45+CD45R/B220-CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+.

Treg Cell Detection Tools and Strategies

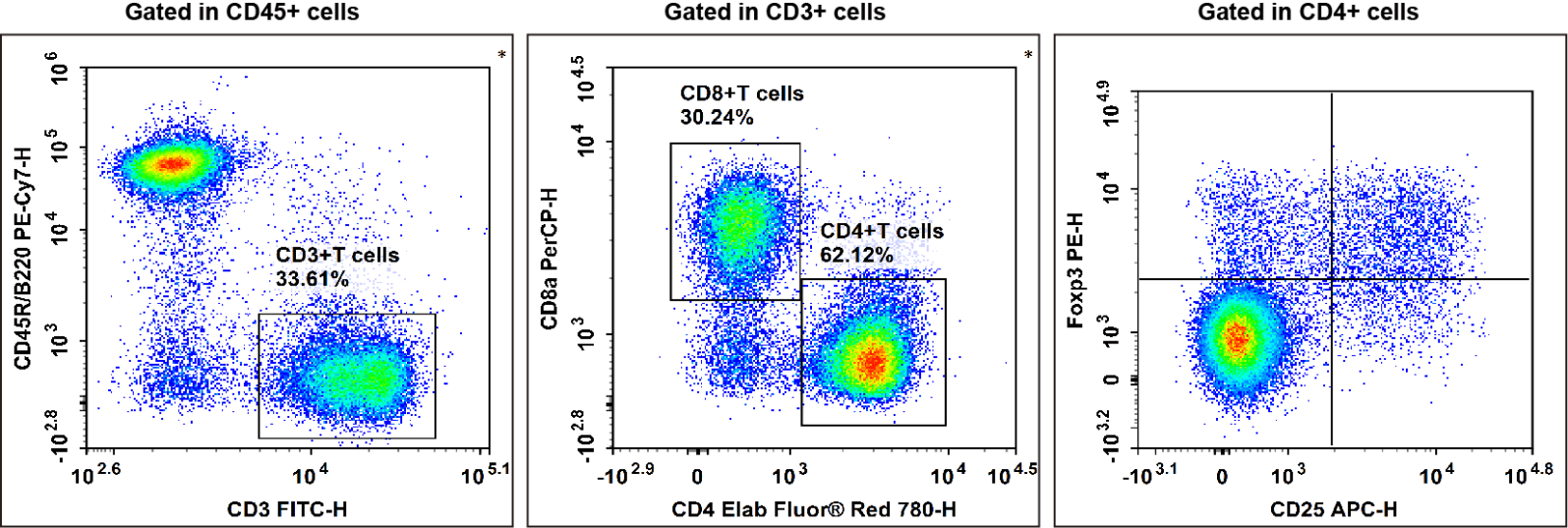

Comprehensive evaluation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) extends beyond FOXP3 detection to include surface marker profiling, functional assays, and epigenetic analysis. Surface markers such as CD4, CD25, and low CD127 help identify enriched Treg populations (e.g.,CD4+CD25hiCD127loFOXP3+), while additional markers like CTLA-4, GITR, and ICOS allow further subtyping[27,30]. Functionally, co-culture suppression assays serve as the gold standard for assessing Treg immunosuppressive capacity, and cytokine secretion profiling (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β, IL-35) via ELISA ,ELISPOT, or flow cytometry provides insight into their mechanistic activity. Epigenetically, TSDR demethylation analysis of the FOXP3 locus offers a stable marker of Treg lineage commitment. Together, these approaches enable a multi-dimensional assessment of Treg identity, frequency, and function in both research and clinical contexts[26,27,30].

Fig.2 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD45, Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Human CD3, FITC Anti-Human CD4, PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD8, PE Anti-Human CD25 and APC Anti-Human CD127, followed by analysise via flow cytometry. Regulatory T cells(Treg cells) exhibit the phenotype of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD127LOW/-CD25+.

Research Advances and Challenges

The functional complexity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in health and disease has driven the development of increasingly refined research tools. Tregs display considerable heterogeneity, particularly tissue‐resident subsets in locations such as the gut and tumor microenvironment, which exhibit distinct phenotypic and functional profiles shaped by local cellular and microbial interactions. This heterogeneity necessitates advanced tools capable of discriminating functionally diverse Treg subpopulations. Furthermore, post‐translational modifications of FOXP3, including acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, significantly influence Treg differentiation, function, and survival, highlighting the need for assays that detect specific FOXP3 modification states. Additionally, Treg proliferation and suppressive activity are regulated by specialized metabolic pathways such as oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation. Tools for analyzing mitochondrial function and metabolic flux are thus essential for uncovering functional deficits and mechanistic insights into Treg biology[31].

In summary, detection tools for Forkhead boxP3 (FOXP3) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) have evolved from the initial identification based on surface markers to a comprehensive evaluation integrating intracellular factors, functional activity, metabolism, and epigenetic features. With the continuous deepening of understanding of Treg biology, more advanced and sophisticated tools will be required in the future to capture the complexity and dynamic changes of Tregs under healthy and disease states, thereby providing new targets and strategies for the treatment of diseases such as autoimmune diseases and cancer.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table 1. Multicolor Panel for Flow Cytometric Analysis of Human and Mouse Regulatory T cells (Tregs)

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Species Reactivity |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Human |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1230S |

Human |

|

CD4 |

SK3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1352C |

Human |

|

CD8 |

OKT-8 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1110J |

Human |

|

CD25 |

BC96 |

PE |

E-AB-F1194D |

Human |

|

CD127 |

A019D5 |

APC |

E-AB-F1152E |

Human |

|

Foxp3 |

FJK-16s |

PE |

E-AB-F1351D |

Mouse |

|

CD45R/B220 |

RA3.3A 1/6.1 |

PE/Cyanine7 |

E-AB-F1112H |

Mouse |

|

CD25 |

PC-61.5.3 |

APC |

E-AB-F1102E |

Mouse |

|

CD4 |

GK1.5 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1097S |

Mouse |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1136Q |

Mouse |

|

CD3 |

17A2 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1013C |

Mouse |

|

CD8a |

53-6.7 |

PerCP |

E-AB-F1104F |

Mouse |

Table 2. Reagents for Human and Mouse Regulatory T cells (Tregs) Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

Human PBMC Separation Solution (P 1.077) |

E-CK-A103 |

|

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

E-CK-A091 |

|

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

E-CK-A109 |

|

10×ACK Lysis Buffer |

E-CK-A105 |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM002N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM003N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM001N |

|

EasySort™ Human CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH001N |

|

EasySortTM Mouse Pan-Naïve T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM006N |

|

EasySortTM Mouse naïve CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM007N |

|

EasySortTM Mouse naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM008N |

|

Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIH001A |

|

Mouse CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIM001A |

|

Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit |

E-CK-A108 |

04 Treg Cells in Health and Disease

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a central role in maintaining the body's immune balance. Through mechanisms such as the secretion of suppressive cytokines, Tregs precisely regulate the intensity of immune responses: they not only prevent excessive activation of the immune system from attacking self-tissues but also avoid insufficient immune responses that impair anti-infective capacity. However, abnormal Treg function triggers distinctly different diseases. If the number of Tregs is insufficient or their function is impaired, the immune system fails to effectively tolerate self-tissues, thereby inducing various autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis; approximately one-tenth of the global population is affected by such diseases. On the contrary, in the tumor microenvironment, Tregs accumulate excessively and potently suppress the cytotoxic function of anti-tumor T cells, acting like an "exploited" immune brake by tumors to help cancer cells evade immune system attack. This finding also provides a key insight for the development of novel cancer immunotherapies by targeting Tregs.

Treg Cells in Autoimmune Diseases

Dysfunction or deficiency in Tregs is a hallmark of various autoimmune conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) . In RA, for example, impaired Treg immunosuppression contributes to chronic inflammation, often accompanied by their reduced frequency and functional capacity. Similarly, Treg dysfunction can exacerbate allergic responses by disrupting their normal inhibition of multiple immune cells. Moreover, reduced Treg number and function are also linked to cardiovascular pathologies such as atherosclerosis[7,18,25].

The central role of Tregs is underscored by the fact that mutations in the FOXP3 gene, a master regulator of Treg development and function, can lead to severe autoimmune disorders. Consequently, therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating Tregs represent a promising frontier. Approaches include the adoptive transfer of exogenous Tregs or the expansion of endogenous Tregs to restore immune balance, with early-phase clinical trials already showing encouraging outcomes[25,26].

Treg Cells in Cancer

In contrast to their protective role in autoimmunity, regulatory T cells (Tregs) predominantly facilitate tumor progression by suppressing antitumor immunity. They accumulate in the tumor microenvironment and peripheral blood of cancer patients, where they inhibit effector T cells and NK cells, thereby dampening antitumor responses and promoting tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Although some contexts, such as colorectal cancer, suggest a potential beneficial role through suppression of inflammation-driven carcinogenesis, the prevailing view supports Treg targeting as a promising immunotherapeutic strategy. For instance, Glycoprotein A repetitions predominant (GARP), specifically expressed on activated Tregs and involved in TGF-β activation, represents a potential therapeutic target to alleviate immunosuppression and enhance antitumor immunity[10,25,26,27].

Treg Cells in Other Conditions

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play multifaceted roles beyond autoimmunity and cancer, contributing to infection responses, tissue repair, angiogenesis, and immunosenescence. Their function is influenced by neural signals and microenvironmental factors, though in certain contexts, Tregs may become "fragile"; they retain Foxp3 expression while losing suppressive capacity, thereby exacerbating inflammation. This functional plasticity underscores the complexity of Treg regulation, which is further modulated by microRNAs and other molecular mechanisms, highlighting their broad therapeutic potential across diverse disease settings[28,29,30].

05 Applications and Future Directions

Regulatory T cells (Tregs), due to their critical role in maintaining immune homeostasis and suppressing aberrant immune responses, have emerged as highly promising therapeutic targets in the fields of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases, and organ transplantation. The future development directions of Treg cell therapy mainly focus on enhancing their specificity, stability, and in vivo efficacy, as well as expanding their application to the treatment of a broader range of diseases[32].

Applications and Future Directions of Treg Regulatory Therapy

Enhancing Specificity and Targeting in Treg Cell Therapy. Advancing the specificity of regulatory T cell (Treg) therapies is essential to improve efficacy and reduce off-target immunosuppression. A key direction involves developing antigen-specific Tregs, engineered with T cell receptors (TCRs) or chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) to recognize disease-relevant autoantigens or alloantigens in transplantation. These cells enable localized immune modulation, thereby minimizing systemic effects. CAR-Tregs represent a major engineering advance, with studies showing that supraphysiological FOXP3 expression enhances their stability and suppressive function even under inflammatory conditions[35]. Furthermore, the integration of biomaterials, such as engineered nanoparticles, facilitates targeted Treg delivery to lymph nodes or inflamed tissues, improving retention and functional persistence[32,33,34]. Collectively, these approaches, ranging from genetic reprogramming to material-assisted delivery, promise to usher in a new era of precision Treg-based immunotherapy for autoimmune disorders and transplant medicine.

Enhancing the Stability and Functional Persistence of Treg Cells. Maintaining the stability and long-term function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) is crucial for effective cell-based immunotherapy. A central challenge is the instability of FOXP3 expression under inflammatory conditions, which can lead to loss of suppressive function and conversion to pathogenic effector phenotypes. Strategies to reinforce Treg identity include gene editing approaches such as CRISPR/Cas to stabilize FOXP3 expression and its associated epigenetic landscape. Furthermore, metabolic reprogramming represents a promising complementary approach[35,36]. Given that Treg survival and function rely on specific metabolic pathways, particularly oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation, modulating these pathways may enhance Treg fitness and activity in hostile inflammatory environments. Together, these interventions aim to generate durable and stable Treg populations capable of sustained immunoregulation in vivo.

Developing Novel Treg Cell Sources. Future advances in Treg-based therapies will focus on creating more clinically suitable and functionally sophisticated cell products. One key direction involves optimizing the induction and expansion of induced Tregs (iTregs) from naïve CD4+T cells, which serve as a critical extrathymic source for establishing immune tolerance and represent a promising alternative to thymus-derived Tregs for clinical application[37]. Another innovative approach centers on engineering "smart" Tregs equipped with biosensing capabilities, enabling them to detect disease-specific signals and deliver spatially and temporally controlled immunosuppression[38]. Together, these strategies aim to provide scalable, specific, and dynamically regulated Treg populations for precision immunotherapy.

Combination Strategies and Delivery Systems for Treg-Based Therapy. To enhance the efficacy and precision of regulatory T cell (Treg) therapies, combination approaches and advanced delivery systems are being actively explored. Combining Treg cells with other immunomodulatory agents, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, antigen-specific treatments, or immune checkpoint inhibitors, may produce synergistic effects. For instance, in cancer immunotherapy, co-targeting Tregs and immune checkpoints can counteract Treg-mediated immunosuppression and potentiate antitumor responses[39]. Furthermore, the use of biomaterials and nanotechnology enables localized delivery of Tregs or immunomodulatory factors to diseased tissues, improving site-specific efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects. Together, these integrated strategies aim to achieve more controlled and potent restoration of immune tolerance.

Therapeutic Potential of Treg Cells in Human Diseases. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) demonstrate considerable promise as a cellular therapy across multiple disease areas. In autoimmune disorders, such as type 1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosi, Treg-based approaches have shown safety and efficacy in preclinical and early clinical studies by restoring immune tolerance and ameliorating tissue injury. In transplantation, Treg administration promotes graft acceptance and may reduce reliance on long-term immunosuppression. Additionally, Treg infusion has proven effective in preventing and treating graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. These cells also play a regulatory role in chronic inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, by suppressing excessive immune activation and supporting tissue repair. Ongoing efforts aim to optimize Treg manufacturing, delivery, and persistence to achieve durable therapeutic outcomes[32,33,34].

Challenges and Opportunities in Treg Cell Therapy

Despite considerable therapeutic promise, the clinical translation of regulatory T cell (Treg)-based therapies faces several key challenges. Treg heterogeneity and functional plasticity, particularly the emergence of "fragile" Tregs that retain FOXP3 but lose suppressive capacity in inflammatory settings, complicate the design of stable and targeted cell products. Scaling up the manufacturing of clinical-grade Tregs under GMP-compliant conditions remains a major bottleneck, requiring optimized protocols for expansion, purification, and cryopreservation. Post-infusion, inadequate persistence, instability, and impaired homing to target tissues further limit therapeutic efficacy. Safety concerns also persist, as excessive Treg activity may potentially increase tumor risk, underscoring the need for balanced and context-aware application. Addressing these challenges through improved cell engineering, production workflows, and mechanistic studies will be crucial to fully realize the potential of Treg therapies[32,33,34,35,36].

In summary, regulatory T cell (Treg) therapy is in a phase of rapid development. With the continuous advancement of genetic engineering, biomaterials science, and basic immunological research, future Treg therapy will move toward a more precise, stable, and effective direction, and is expected to provide breakthrough therapeutic regimens for a variety of immune-mediated diseases.

06 Conclusion: From Nobel Discovery to Research Innovation

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine not only recognizes three scientists for their groundbreaking contributions to the discovery of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and the FOXP3 gene but has also ignited a new wave of advancement in the field of immunotherapy. This breakthrough in basic science has progressed from a conceptual advance to a diverse range of practical applications, truly embodying the scientific value of "investigating things to exhaust principles" and ultimately leading to "applying knowledge to serve public welfare."

The discovery of Tregs has filled a critical gap in the understanding of immune homeostasis, revealing the "regulatory brakes" that restrain the immune system from attacking the body’s self-tissues. The FOXP3 gene, functioning as the "master regulator" of Tregs, has emerged as the cornerstone for elucidating this regulatory mechanism. These foundational breakthroughs are now exerting a profound impact on human health:

In the treatment of autoimmune diseases, novel strategies to modulate Treg function offer new hope for patients. For instance, low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) therapy, capable of selectively promoting Treg proliferation, has demonstrated efficacy in clinical studies for conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

In cancer therapy, targeting Tregs within the tumor microenvironment (TME) is improving the efficacy of immunotherapies. Next-generation CTLA-4 antibodies, e.g., HBM4003 developed by Harbour BioMed, are engineered to specifically deplete intratumoral Tregs, exhibiting promising efficacy signals in malignancies including colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.

In infectious disease research, elucidating how pathogens hijack Tregs to evade immune surveillance is identifying new therapeutic targets.

As Shimon Sakaguchi noted at a Tokyo press conference, "Humanity is expected to achieve a cure for cancer within two decades." This confidence is rooted in a profound understanding of the immune system’s regulatory mechanisms and full acknowledgment of Tregs’ therapeutic potential.

From Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs to ongoing scientific innovations, research on Tregs continues to advance. With the increasing understanding of FOXP3-mediated regulation and the development of more precise Treg detection and modulation technologies, there is reason to anticipate that Treg-based therapies will play an increasingly pivotal role in the future of medicine, offering health hope to more patients.

References:

[1] Offord, C. (2025). Research on immune system’s ‘police’ garners Nobel. Science, 390(6769), 112–113. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aec9015.

[2] Shi, P., Yu, Y., Xie, H., Yin, X., Chen, X., Zhao, Y., & Zhao, H. (2025). Recent advances in regulatory immune cells: exploring the world beyond Tregs. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1530301.

[3] Wardell, C. M., Boardman, D. A., & Levings, M. K. (2024). Harnessing the biology of regulatory T cells to treat disease. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 24(2), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-024-01089-x.

[4] Hu, Y., Cruz, H., Santosh Nirmala, S., & Fuchs, A. (2025). Unlocking the therapeutic potential of thymus-isolated regulatory T cells. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1612360.

[5] Sakaguchi S , Sakaguchi N , Asano M ,et al.Pillars article: immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor α-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1995.[J].Journal of Immunology, 2011, 186(7):3808-3821.

[6] Brunkow M E , Jeffery E W , Hjerrild K A ,et al.Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse.[J].Nature Genetics, 2001, 27(1):68.DOI:10.1038/83784.

[7] Wildin R S , Ramsdell F , Peake J ,et al.X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy.[J].Nature Genetics, 2001, 27(1):18-20.DOI:10.1038/83707.

[8] Bennett C L , Christie J , Ramsdell F ,et al.The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3.[J].Nature Genetics, 2001, 27(1):20-21.DOI:10.1038/83713.

[9] Hori S , Nomura T , Sakaguchi S .Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3[J].Science, 2003, 299(5609):1057-1061.DOI:10.1126/science.1079490.

[10] Wing, J. B., Tanaka, A., & Sakaguchi, S. (2019). Human FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cell Heterogeneity and Function in Autoimmunity and Cancer. Immunity, 50(2), 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.020.

[11] Wu, Y., Borde, M., Heissmeyer, V., Feuerer, M., Lapan, A. D., Stroud, J. C., Bates, D. L., Guo, L., Han, A., Ziegler, S. F., Mathis, D., Benoist, C., Chen, L., & Rao, A. (2006). FOXP3 Controls Regulatory T Cell Function through Cooperation with NFAT. Cell, 126(2), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042.

[12] Zheng, Y., & Rudensky, A. Y. (2007). Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nature Immunology, 8(5), 457–462. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1455.

[13] Fleskens, V., Minutti, C. M., Wu, X., Wei, P., Pals, C. E. G. M., McCrae, J., Hemmers, S., Groenewold, V., Vos, H.-J., Rudensky, A., Pan, F., Li, H., Zaiss, D. M., & Coffer, P. J. (2019). Nemo-like Kinase Drives Foxp3 Stability and Is Critical for Maintenance of Immune Tolerance by Regulatory T Cells. Cell Reports, 26(13), 3600-3612.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.087.

[14] Shanru,Li,Michael,et al.Transcriptional and DNA Binding Activity of the Foxp1/2/4 Family Is Modulated by Heterotypic and Homotypic Protein Interactions.[J].Molecular & Cellular Biology, 2004.DOI:10.1128/MCB.24.2.809-822.2004.

[15] Henschel, P., Landwehr-Kenzel, S., Engels, N., Schienke, A., Kremer, J., Riet, T., Redel, N., Iordanidis, K., Saetzler, V., John, K., Heider, M., Hardtke-Wolenski, M., Wedemeyer, H., Jaeckel, E., & Noyan, F. (2023). Supraphysiological FOXP3 expression in human CAR-Tregs results in improved stability, efficacy, and safety of CAR-Treg products for clinical application. Journal of Autoimmunity, 138, 103057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2023.103057.

[16] Hebbar Subramanyam, S., Turyne Hriczko, J., Schulz, S., Look, T., Goodarzi, T., Clarner, T., Scheld, M., Kipp, M., Verjans, E., Böll, S., Neullens, C., Costa, I., Li, Z., Gan, L., Denecke, B., Schippers, A., Floess, S., Huehn, J., Schmitt, E., … Tenbrock, K. (2025). CREB regulates Foxp3+ST-2+ TREGS with enhanced IL-10 production. Frontiers in Immunology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1601008.

[17] Wang, X., Cheng, H., Shen, Y., & Li, B. (2021). Metabolic Choice Tunes Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cell Function. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (pp. 81–94). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6407-9_5.

[18] Hosseini, S. A., Ajorlou, P., Mousavi, P., & Shekari, M. (2025). Revealing the regulatory role of lncRNAs SNHG1 and CRNDE on Th17/Treg imbalance in diabetic kidney disease. Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-025-01802-z

[19] Niedbala,Wanda,Beilei Cai. Nitric oxide induces CD4+CD25+ Foxp3- regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25- T cells via p53, IL-2, and OX40.[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007.DOI:10.1073/pnas.0703725104.

[20] Mu, J., Tai, X., Iyer, S. S., Weissman, J. D., Singer, A., & Singer, D. S. (2014). Regulation of MHC Class I Expression by Foxp3 and Its Effect on Regulatory T Cell Function. The Journal of Immunology, 192(6), 2892–2903. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1302847.

[21] Kusuba, N., Kitoh, A., Dainichi, T., Honda, T., Otsuka, A., Egawa, G., Nakajima, S., Miyachi, Y., & Kabashima, K. (2018). Inhibition of IL-17–committed T cells in a murine psoriasis model by a vitamin D analogue. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(3), 972-981.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.033.

[22] Yun, H., Yee, M. B., Lathrop, K. L., Kinchington, P. R., Hendricks, R. L., & St. Leger, A. J. (2020). Production of the Cytokine VEGF-A by CD4+ T and Myeloid Cells Disrupts the Corneal Nerve Landscape and Promotes Herpes Stromal Keratitis. Immunity, 53(5), 1050-1062.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.013.

[23] Weitering, T. J., Takada, S., Weemaes, C. M. R., van Schouwenburg, P. A., & van der Burg, M. (2021). ATM: Translating the DNA Damage Response to Adaptive Immunity. Trends in Immunology, 42(4), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2021.02.001.

[24] Li, H., Zhang, Y., Gao, S., & Yin, H. (2025). T cell-intrinsic cGAS-CTCF regulation maintains regulatory T cell development and function. Cell Reports, 44(10), 116302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116302.

[25] Eyad E , Varun S N .T-Regulatory Cells in Health and Disease[J].Journal of Immunology Research, 2018, 2018:1-2.DOI:10.1155/2018/5025238.

[26] Scheinecker C , Gschl L , Bonelli M .Treg cells in health and autoimmune diseases: New insights from single cell analysis.[J].J Autoimmun, 2020.DOI:10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102376.

[27] A R S , B E E A .FoxP3+ T regulatory cells in cancer: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets - ScienceDirect[J].Cancer Letters, 2020.

[28] Ueno, M. (2021). Restoring neuro-immune circuitry after brain and spinal cord injuries. International Immunology, 33(6), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxab017.

[29] Miao, W., Zhao, Y., Huang, Y., Chen, D., Luo, C., Su, W., & Gao, Y. (2020). IL-13 Ameliorates Neuroinflammation and Promotes Functional Recovery after Traumatic Brain Injury. The Journal of Immunology, 204(6), 1486–1498. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1900909.

[30] Lužnik, Z., Anchouche, S., Dana, R., & Yin, J. (2020). Regulatory T Cells in Angiogenesis. The Journal of Immunology, 205(10), 2557–2565. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2000574.

[31] Goswami, T. K., Singh, M., Dhawan, M., Mitra, S., Emran, T. B., Rabaan, A. A., Mutair, A. A., Alawi, Z. A., Alhumaid, S., & Dhama, K. (2022). Regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their therapeutic potential against autoimmune disorders – Advances and challenges. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2035117.

[32] Boardman, D. A., & Levings, M. K. (2022). Emerging strategies for treating autoimmune disorders with genetically modified Treg cells. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 149(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.11.007.

[33] Qu, G., Chen, J., Li, Y., Yuan, Y., Liang, R., & Li, B. (2022). Current status and perspectives of regulatory T cell-based therapy. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 49(7), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2022.05.005.

[34] Selck, C., & Dominguez-Villar, M. (2021). Antigen-Specific Regulatory T Cell Therapy in Autoimmune Diseases and Transplantation. Frontiers in Immunology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.661875.

[35] Riet, T., & Chmielewski, M. (2022). Regulatory CAR-T cells in autoimmune diseases: Progress and current challenges. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.934343.

[36] Yu, L., Fu, Y., Miao, R., Cao, J., Zhang, F., Liu, L., Mei, L., & Ou, M. (2024). Regulatory T Cells and Their Derived Cell Pharmaceuticals as Emerging Therapeutics Against Autoimmune Diseases. In Advanced Functional Materials.

[37] Alvarez-Salazar, E. K., Cortés-Hernández, A., Arteaga-Cruz, S., & Soldevila, G. (2024). Induced regulatory T cells as immunotherapy in allotransplantation and autoimmunity: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 116(5), 947–965. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleuko/qiae062.

[38] Bittner, S., Hehlgans, T., & Feuerer, M. (2023). Engineered Treg cells as putative therapeutics against inflammatory diseases and beyond. Trends in Immunology, 44(6), 468–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2023.04.005.

[39] Hosseinalizadeh, H., Rabiee, F., Eghbalifard, N., Rajabi, H., Klionsky, D. J., & Rezaee, A. (2023). Regulating the regulatory T cells as cell therapies in autoimmunity and cancer. Frontiers in Medicine, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1244298