Microglia, as the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), are crucial for brain development, homeostasis, and response to damage and infection[1,3].These cells play dynamic and multifaceted roles, interacting with neurons and other brain structures to maintain neural homeostasis[2]. Their functions extend beyond classical immune responses, encompassing essential physiological roles for proper brain development and the maintenance of adult brain homeostasis[3].

This review summarizes the primary roles of microglia, covering their essential functions in the healthy brain and their dichotomous roles in injury response and repair. It further examines their involvement in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis and discusses phagocytic activities across development and aging. The article also analyzes distinct microglial phenotypes and their influence on disease progression, concluding with current strategies for therapeutically targeting microglia in neurological disorders.

Table of Contents

1. What are the primary functions of microglia in the healthy brain?

2. The dual role of microglia in brain injury and repair

3. Microglia and their role in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis

4. Microglial phagocytosis in the developing and aging brain

5. Microglial phenotypes and their impact on disease progression

6. Therapeutic targeting of microglia in neurological diseases

01 What are the primary functions of microglia in the healthy brain?

In the healthy CNS, microglia maintain a “resting” or “surveillant” phenotype, characterized by a ramified morphology with fine, highly motile processes that continuously scan the brain parenchyma[4]. This constant surveillance enables microglial cells to perform multiple essential functions that underpin brain homeostasis.

Microglial cells perform multiple essential functions sustaining brain homeostasis. First, as a core function, microglia mediate synaptic pruning and refinement: during brain development, they recognize and phagocytose excess or immature synapses via the interaction between complement component C3 and its microglial receptor CR3 to shape specific and efficient neural circuits, while this process persists at a low level in adults to maintain synaptic plasticity critical for learning and memory, with microglial depletion leading to impaired pruning and cognitive deficits[5]. Second, microglia regulate neurogenesis in the adult subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) by secreting neurotrophic factors like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) to promote neural stem or progenitor cell (NSPC) proliferation, differentiation and survival, and by clearing apoptotic cells or debris in neurogenic niches to optimize the microenvironment[6]. Third, they maintain blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity through interactions with endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes in the neurovascular unit, and secret tight junction proteins and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) to prevent blood-borne substance leakage[7,8]. Fourth, Microglial cells are involved in the modulation of neural activity. Emerging evidence indicates that microglial processes make direct contact with synapses and regulate synaptic transmission by releasing cytokines and neurotransmitters. For example, microglia-derived tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) can enhance synaptic strength by increasing the expression of AMPA receptors on the postsynaptic membrane[7,8].

02 The dual role of microglia in brain injury and repair

Brain injury, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), ischemic stroke, and spinal cord injury (SCI), triggers a rapid activation of microglia. Activated microglia exhibit a dual role of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory or repair-promoting, which is closely related to the stage of injury and the microenvironmental cues[9].

In the early stage of injury (within hours to days), microglia are rapidly activated into a pro-inflammatory phenotype (often referred to as M1-like phenotype). They secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6)), chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CXCL10), and reactive oxygen species (ROS)[7,8,10]. This pro-inflammatory response plays a crucial role in clearing the invading pathogens, removing necrotic cells and cellular debris, and recruiting peripheral immune cells (such as monocytes or macrophages) to the injury site. However, excessive and prolonged pro-inflammatory activation of microglia can cause secondary brain damage by inducing neurotoxicity, disrupting the BBB, and exacerbating tissue edema and inflammation. For example, in ischemic stroke, pro-inflammatory microglia-derived ROS and nitric oxide (NO) can directly damage the cell membrane and DNA of neurons, leading to the expansion of the ischemic penumbra[11,12].

In the late stage of injury (days to weeks), microglia gradually switch to an anti-inflammatory and repair-promoting phenotype (M2-like phenotype). This phenotypic switch is regulated by a variety of factors, including anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)), growth factors, and the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells[13]. M2-like microglia secrete neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF), anti-inflammatory cytokines, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components (e.g., fibronectin, laminin), which promote the survival of residual neurons, the migration and differentiation of NSPCs (neural stem/progenitor cells), the repair of the BBB, and the formation of new blood vessels. Additionally, M2-like microglia enhance phagocytic activity to clear apoptotic cells and cellular debris, thereby reducing the inflammatory microenvironment and promoting tissue repair. For instance, in TBI models, adoptive transfer of M2-like microglia significantly improves neurological function recovery by reducing brain edema and promoting neurogenesis[9,14,15].

The balance between the M1 and M2 phenotypes of microglia is critical for the outcome of brain injury. Dysregulation of this balance, such as persistent M1 activation or insufficient M2 polarization, can lead to delayed tissue repair and long-term neurological deficits. Therefore, modulating the phenotypic switch of microglia has become a potential therapeutic strategy for brain injury.

03 Microglia and their role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and the formation of intracellular inclusions known as Lewy bodies, which are primarily composed of aggregated α-synuclein (α-syn)[16]. Accumulating evidence indicates that microglial activation and neuroinflammation play a central role in the initiation and progression of PD.

One of the key mechanisms by which microglia contribute to PD pathogenesis is the response to aggregated α-syn. α-syn is a soluble presynaptic protein that, when misfolded and aggregated, becomes neurotoxic and can activate microglia through multiple pathways[17]. For example, aggregated α-syn can bind to toll-like receptors (TLRs) (e.g., TLR2, TLR4) and scavenger receptors (e.g., CD36) on the microglial surface, triggering the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, thereby inducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic factors[17,18]. Additionally, aggregated α-syn can be phagocytosed by microglia, however, the inefficient degradation of α-syn aggregates leads to their accumulation in microglia, further enhancing microglial activation and neuroinflammation in a positive feedback loop[17].

Another important mechanism is the neurotoxicity mediated by activated microglia. Persistently activated microglia secrete a variety of neurotoxic substances, including TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS, and NO, which directly damage dopaminergic (DA) neurons[7,8,10]. For example, IL-1β can induce the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in microglia and astrocytes, leading to the production of large amounts of NO. NO reacts with superoxide anions to form peroxynitrite (ONOO-), a highly toxic free radical that causes oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, ultimately leading to DA neuron death[17,19]. Moreover, activated microglial cells can disrupt the autophagic flux of DA neurons, impairing the clearance of misfolded proteins and exacerbating neuronal damage[17].

Genetic studies have further confirmed the involvement of microglia in PD pathogenesis. Mutations in genes such as LRRK2 (leucine-rich repeat kinase 2), GBA1 (glucocerebrosidase 1), and TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2), which are highly expressed in microglia, are associated with an increased risk of PD. For example, TREM2 is a microglial surface receptor that regulates microglial phagocytosis and survival. Loss-of-function mutations in TREM2 impair the phagocytic ability of microglia to clear aggregated α-syn and apoptotic cells, leading to the accumulation of neurotoxic substances and enhanced neuroinflammation[16,20].

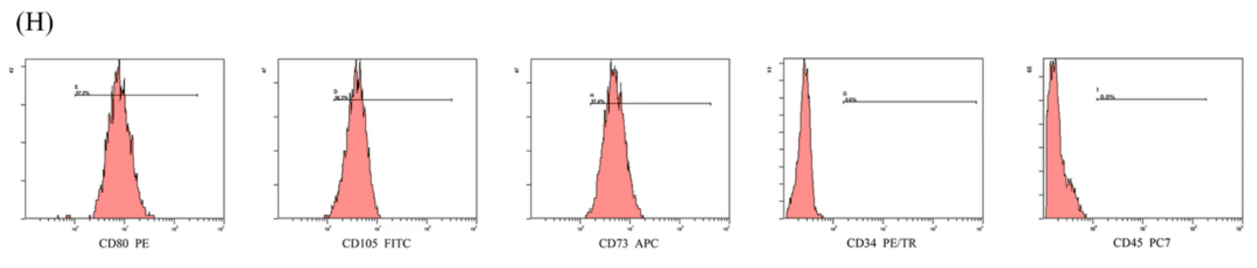

Fig. 1 Flow cytometric analysis of ADSCs (human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells) were co-cultured with SH-SY5Y cells,then were labeled with APC anti-CD73, PE anti-CD90, FITC anti-CD105 and PE anti-CD34, CD45[34].

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table 1. Reagents for ADSCs Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

APC Anti-Human CD73 Antibody[AD2] |

E-AB-F1242E |

|

PE Anti-Human CD90 Antibody[5E10] |

E-AB-F1167D |

|

Elab Fluor® 488 Anti-Human CD105 Antibody[SN6] |

E-AB-F1310L |

|

PE Anti-Human CD34 Antibody[581] |

E-AB-F1143D |

|

PE Anti-Human CD45 Antibody[HI30] |

E-AB-F1137D |

04 Microglial phagocytosis in the developing and aging brain

Phagocytosis, the process by which cells engulf and degrade foreign particles, apoptotic cells, and cellular debris, is a fundamental function of microglia. The phagocytic activity of microglia undergoes significant changes during brain development and aging, and this dynamic regulation is crucial for brain homeostasis and function[17,21].

In the developing brain, microglial phagocytosis is highly active and participates in multiple key developmental processes. As mentioned earlier, microglia phagocytose excess synapses to refine neural circuits. In addition, microglial cells clear apoptotic neurons and NSPCs (neural stem/progenitor cells) generated during neurogenesis, which is essential for maintaining the balance of cell numbers in the developing brain. For example, during the development of the cerebral cortex, a large number of neurons undergo programmed cell death (PCD), microglia recognize these apoptotic neurons through the “eat-me” signals (e.g., phosphatidylserine (PS)) exposed on their surface and phagocytose them, thereby preventing the release of intracellular toxic substances and avoiding inflammatory responses[21]. Furthermore, microglia phagocytose cellular debris and extracellular matrix components to remodel the brain tissue structure, creating favorable conditions for neural migration and axon guidance[5,21].

In the aging brain, the phagocytic function of microglia is significantly impaired, which contributes to the accumulation of cellular debris, misfolded proteins, and apoptotic cells, thereby increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases[22]. Multiple factors are involved in the decline of microglial phagocytic activity with age. First, the expression of phagocytic receptors (e.g., TREM2, CD36, MerTK) on the microglial surface decreases with age, reducing the ability of microglia to recognize and bind to phagocytic targets. Second, the intracellular signaling pathways regulating phagocytosis (e.g., PI3K/Akt, MAPK) are dysregulated in aged microglia, impairing the cytoskeletal rearrangement and vesicle trafficking required for phagocytosis. Third, the aged brain microenvironment is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation, which can further suppress the phagocytic function of microglia. For example, chronic exposure to low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines can downregulate the expression of TREM2 in microglia, leading to impaired phagocytosis of amyloid-β (Aβ) and α-syn aggregates[23,24].

Notably, the impairment of microglial phagocytosis in the aging brain forms a vicious cycle with neuroinflammation and protein aggregation. The accumulation of misfolded proteins and cellular debris activates microglia, leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, these cytokines further impair microglial phagocytosis, resulting in more severe accumulation of toxic substances and exacerbation of neuroinflammation. Therefore, restoring the phagocytic function of aged microglia may be a promising strategy to delay brain aging and prevent neurodegenerative diseases[24,25].

05 Microglial phenotypes and their impact on disease progression

Traditionally, microglial activation has been classified into two opposing phenotypes: the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the anti-inflammatory and repair-promoting M2 phenotype. However, this binary classification system is oversimplified, as recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies have revealed that microglia exhibit a high degree of phenotypic and functional heterogeneity in different diseases and disease stages, forming a continuous spectrum of phenotypes[26].

The M1-like phenotype is typically induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ). M1-like microglia express specific markers, such as iNOS, CD86, and MHC class II molecules, and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines, and neurotoxic factors (ROS, NO). In neurological diseases, excessive M1-like microglial activation promotes disease progression by inducing neurotoxicity, exacerbating inflammation, and disrupting tissue homeostasis. For example, in Alzheimer's disease (AD), M1-like microglia surrounding Aβ plaques secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which accelerate the deposition of Aβ and the hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, leading to the loss of neurons and cognitive decline[27].

The M2-like phenotype is induced by anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) and growth factors (e.g., CSF-1). M2-like microglia can be further subdivided into M2a, M2b, and M2c subtypes based on their functional characteristics and marker expression. M2a microglia, induced by IL-4/IL-13, express CD206, Arg1, and Ym1, and are involved in tissue repair and anti-inflammation. M2b microglia, induced by immune complexes and TLR ligands, secrete both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, regulating the inflammatory response. M2c microglia, induced by IL-10 and TGF-β, express CD163 and MerTK, and are specialized in phagocytosis and tissue remodeling[16,28]. In neurological diseases, M2-like microglia exert neuroprotective effects by clearing toxic aggregates, promoting neurogenesis, and suppressing inflammation. For example, in multiple sclerosis (MS), M2-like microglia phagocytose myelin debris and secrete neurotrophic factors, promoting the remyelination of axons[15].

Beyond the classical M1/M2 classification paradigm, a spectrum of pivotal markers and emerging phenotypes enables a more comprehensive characterization of the complex activation states and functional profiles of microglia. Fundamental identity markers, such as ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) and transmembrane protein 119 (TMEM119), serve to delineate cellular morphology and density, and to specifically discriminate microglia from other central nervous system (CNS) macrophages[34,35,38], respectively. Markers denoting functional states encompass: purinergic receptor P2Y12 (a signature of the quiescent state, which is downregulated upon activation), cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68, closely associated with phagocytic activation), and Ki-67 (a well-recognized proliferation marker)[37,38]. Furthermore, key regulatory molecules including triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) and CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) exert a profound impact on the functional phenotypes of microglia, for instance, TREM2 orchestrates the formation and phagocytic clearance capacity of disease-associated microglia (DAM) in neurodegenerative disorders, whereas CX3CR1 is implicated in modulating their neurotoxic potential and transition toward a reparative phenotype[37,38,39]. Collectively, these markers establish a multidimensional assessment framework that transcends the oversimplified binary classification, thereby enabling a more precise delineation of the dynamic alterations of microglia during physiological and pathological processes.

Table 2. Overview of Microglial Phenotypes and Functions[16,17,20,23,24,27,28,34,35,37,38]

|

Phenotype Category |

Key Activating Signals |

Primary Markers / Secreted Factors |

Core Functions |

|

Pro-inflammatory / Neurotoxic Phenotype (M1-like) |

IFN-γ, LPS, TNF-α, Aβ |

Markers: iNOS, CD86, MHC II; Secreted Factors: IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, ROS/RNS. |

Initiates acute immune defense and pathogen clearance, sustained activation exerts neurotoxic effects. |

|

Anti-inflammatory / Neuroprotective Phenotype (M2-like) |

IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, TGF-β |

Markers: Arg-1, CD206, YM1/2; Secreted Factors: IL-10, GDNF, IGF-1, TGF-β. |

Suppresses inflammation, clears debris, promotes tissue repair, and supports neuronal survival and synaptic remodeling. |

|

Disease-Associated Microglia (DAM) |

Aβ, Tau proteins, Lipoproteins (e.g., ApoE) |

Markers: TREM2, ApoE, LPL (Unique gene-expression module) |

Dual Functionality: Can engage in phagocytic clearance of pathological proteins (e.g., Aβ) but may also exist in a dysfunctional, chronically inflamed state. |

|

Identification Phenotype of Microglia |

/ |

Markers: TMEM119, Iba1, P2RY12 |

Specifically discriminate microglia from other central nervous system (CNS) macrophages. |

|

Activation Phenotype of Microglia |

/ |

Markers: CD68, CX3CR1, Ki-67, TREM2 |

Reflecting the activation status and function of microglia. |

The phenotypic transition of microglia is regulated by a complex network of factors, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and environmental cues. The balance between different microglial phenotypes directly affects the outcome of neurological diseases. Targeting the phenotypic regulation of microglia to promote the transition from M1-like to M2-like phenotype has become a key direction in the development of therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases.

06 Therapeutic targeting of microglia in neurological diseases

Given the critical role of microglia in the pathogenesis of various neurological diseases, targeting microglia to modulate their activation state, phenotypic transition, and functional activity has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach, with current strategies mainly including four categories:

First, modulating microglial activation and phenotypic transition, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen inhibit microglial activation via NF-κB signaling[29], natural compounds such as curcumin promote M2-like polarization through Nrf2/ARE pathway[19,31], and TLR4 inhibitors block aggregated α-syn/Aβ-induced microglial activation[17,18].

Second, enhancing phagocytic function, TREM2 agonists strengthen microglial clearance of Aβ/α-syn aggregates, while MerTK activators promote myelin debris phagocytosis to accelerate remyelination in multiple sclerosis (MS)[15,23].

Third, targeting key signaling pathways, NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7082 alleviates neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke, and CSF-1R inhibitors induce transient microglial depletion, with repopulated cells showing anti-inflammatory properties in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)[32,33].

Fourth, cell-based therapies, adoptive transfer of ex vivo polarized M2-like microglia or mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived microglia-like cells exerts neuroprotective effects, as seen in Parkinson’s disease (PD) models where M2-like microglia transplantation reduces dopaminergic (DA) neuron loss and improves motor function[16,31].

Microglia are multifunctional cells that play a crucial role in maintaining brain homeostasis, participating in brain development, and regulating the pathogenesis of neurological diseases. From the surveillance and synaptic pruning in the healthy brain to the dual role in brain injury and repair, from the involvement in PD pathogenesis to the changes in phagocytic function during brain development and aging, microglia exhibit remarkable phenotypic and functional plasticity. Targeting microglia to modulate their activation state and functional activity has become a promising therapeutic approach for neurological diseases. However, the complexity of microglial biology, such as the phenotypic heterogeneity and the dynamic regulation of functions, requires further in-depth studies. With the continuous development of new technologies, such as scRNA-seq, live imaging, and gene editing, we are expected to gain a more comprehensive understanding of microglial biology, which will lay a solid foundation for the development of novel and effective therapeutic interventions for CNS disorders[30].

References:

[1] Kent, S. A., & Miron, V. E. (2023). Microglia regulation of central nervous system myelin health and regeneration. Nature Reviews Immunology, 24(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-023-00907-4.

[2] Bilimoria, P. M., & Stevens, B. (2015). Microglia function during brain development: New insights from animal models. Brain Research, 1617, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.032.

[3] Sierra, A., Miron, V. E., Paolicelli, R. C., & Ransohoff, R. M. (2024). Microglia in Health and Diseases: Integrative Hubs of the Central Nervous System (CNS). Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 16(8), a041366. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041366.

[4] Davalos D , Grutzendler J , Yang G ,et al.ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo.[J].Nature Neuroscience, 2005, 8(6):752-758.DOI:10.1038/nn1472.

[5] Schafer D , Lehrman E , Kautzman A ,et al.Microglia Sculpt Postnatal Neural Circuits in an Activity and Complement-Dependent Manner[J].Neuron, 2012.DOI:10.1016/S0920-9964(12)70039-7.

[6] Ziv Y , Ron N , Butovsky O ,et al.Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood.[J].Nature Neuroscience, 2006, 9(2):268-275.DOI:10.1038/nn1629.

[7] Thurgur, H., & Pinteaux, E. (2019). Microglia in the Neurovascular Unit: Blood–Brain Barrier–microglia Interactions After Central Nervous System Disorders. Neuroscience, 405, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.06.046.

[8] Zhang, S., Meng, R., Jiang, M., Qing, H., & Ni, J. (2024). Emerging Roles of Microglia in Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Aging and Neurodegeneration. Current Neuropharmacology, 22(7), 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159x21666230203103910.

[9] Ajoolabady, A., Kim, B., Abdulkhaliq, A. A., Ren, J., Bahijri, S., Tuomilehto, J., Borai, A., Khan, J., & Pratico, D. (2025). Dual role of microglia in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of Disease, 216, 107133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2025.107133.

[10] Yang, G., Xu, X., Gao, W., Wang, X., Zhao, Y., & Xu, Y. (2025). Microglia-orchestrated neuroinflammation and synaptic remodeling: roles of pro-inflammatory cytokines and receptors in neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2025.1700692.

[11] Wang, Z., & Chen, G. (2023). Immune regulation in neurovascular units after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiology of Disease, 179, 106060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2023.106060.

[12] Dirnagl U , Iadecola C , Moskowitz M A .Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view.[J].Trends in Neurosciences, 1999, 22(9):391-397.DOI:10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01401-0.

[13] Fernando,O,Martinez,et al.The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. [J]. F1000prime Reports, 2014.DOI:10.12703/P6-13.

[14] Wendimu, M. Y., & Hooks, S. B. (2022). Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells, 11(13), 2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132091.

[15] Pak, M. E., Kim, Y.-J., Kim, H., Shin, C. S., Yoon, J.-W., Jeon, S., Song, Y.-H., & Kim, K. (2023). Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of the Human Milk Oligosaccharide, 2′-Fucosyllactose, Exerted via Modulation of M2 Microglial Activation in a Mouse Model of Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. Antioxidants, 12(6), 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12061281.

[16] Gao, C., Jiang, J., Tan, Y., & Chen, S. (2023). Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01588-0.

[17] Yu, H., Chang, Q., Sun, T., He, X., Wen, L., An, J., Feng, J., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Metabolic reprogramming and polarization of microglia in Parkinson’s disease: Role of inflammasome and iron. Ageing Research Reviews, 90, 102032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102032.

[18] Ravenhill, S. M., Evans, A. H., & Crewther, S. G. (2023). Escalating Bi-Directional Feedback Loops between Proinflammatory Microglia and Mitochondria in Ageing and Post-Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants, 12(5), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12051117.

[19] Dauer W , Przedborski S .Parkinson's Disease: Mechanisms and Models - ScienceDirect[J].Neuron, 2003.DOI:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00568-3.

[20] Quick, J. D., Silva, C., Wong, J. H., Lim, K. L., Reynolds, R., Barron, A. M., Zeng, J., & Lo, C. H. (2023). Lysosomal acidification dysfunction in microglia: an emerging pathogenic mechanism of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02866-y.

[21] Tremblay, Marie-ève, Lowery R L , Majewska A K ,et al.Microglial Interactions with Synapses Are Modulated by Visual Experience[J].PLoS Biology, 2010, 8(11):e1000527-.DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000527.

[22] Graeber M B , Li W , Rodriguez M L .Role of microglia in CNS inflammation[J].Febs Letters, 2011, 585(23):3798-3805.DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.033.

[23] Rommy V B ,Eugenín-von Bernhardi Laura,Eugenín Jaime.Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration[J].Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2015, 7(124):124.DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2015.00124.

[24] Selkoe, D. J. (2024). The advent of Alzheimer treatments will change the trajectory of human aging. Nature Aging, 4(4), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00611-5.

[25] Liu, N., Liang, X., Chen, Y., & Xie, L. (2024). Recent trends in treatment strategies for Alzheimer’s disease and the challenges: A topical advancement. Ageing Research Reviews, 94, 102199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102199.

[26] Tao Yin,Metin Yesiltepe,Luciano D'Adamio.Functional BRI2-TREM2 interactions in microglia: implications for Alzheimer's and related dementias[J].EMBO reports, 2024, 25(3):35.DOI:10.1038/s44319-024-00077-x.

[27] Heneka M T , Kummer M P , Latz E .Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease[J].Nature Reviews Immunology, 2014, 14(7):463-477.DOI:10.1038/nri3705.

[28] Var, S. R., Strell, P., Johnson, S. T., Roman, A., Vasilakos, Z., & Low, W. C. (2023). Transplanting Microglia for Treating CNS Injuries and Neurological Diseases and Disorders, and Prospects for Generating Exogenic Microglia. Cell Transplantation, 32. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636897231171001.

[29] Moore A H , Bigbee M J , Boynton G E ,et al.Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease: Reconsidering the Role of Neuroinflammation[J].Pharmaceuticals, 2010, 3(6).DOI:10.3390/ph3061812.

[30] You, Y., Chen, Z., & Hu, W.-W. (2024). The role of microglia heterogeneity in synaptic plasticity and brain disorders: Will sequencing shed light on the discovery of new therapeutic targets? Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 255, 108606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2024.108606.

[31] Long, Y., Li, X., Deng, J., Ye, Q., Li, D., Ma, Y., Wu, Y., Hu, Y., He, X., Wen, J., Shi, A., Yu, S., Shen, L., Ye, Z., Zheng, C., & Li, N. (2024). Modulating the polarization phenotype of microglia – A valuable strategy for central nervous system diseases. Ageing Research Reviews, 93, 102160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102160.

[32] Yousefizadeh, A., Piccioni, G., Saidi, A., Triaca, V., Mango, D., & Nisticò, R. (2022). Pharmacological targeting of microglia dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease: Preclinical and clinical evidence. Pharmacological Research, 184, 106404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106404.

[33] Krukowski, K., Nolan, A., Becker, M., Picard, K., Vernoux, N., Frias, E. S., Feng, X., Tremblay, M.-E., & Rosi, S. (2021). Novel microglia-mediated mechanisms underlying synaptic loss and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 98, 122–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.08.210.

[34] Yu X , Fang Y , Zhang J ,et al.Glycyrrhizic acid combined with human adipose-derived MSCs synergistically alleviates the MPP+/MPTP-induced parkinson's disease by inducing autophagy through PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α pathway[J].STEM CELL RESEARCH & THERAPY, 2025, 2025(000).DOI:10.1186/s13287-025-04626-6.

[35] Razenkova, V. A., Kirik, O. V., & Korzhevskii, D. E. (2025). Microglia Immunophenotyping in Paraffin Sections of the Brain. Cell and Tissue Biology, 19(6), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1990519x25600541.

[36] He, H., He, H., Mo, L., You, Z., & Zhang, J. (2024). Priming of microglia with dysfunctional gut microbiota impairs hippocampal neurogenesis and fosters stress vulnerability of mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 115, 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.10.031.

[37] Wang, J., Chen, H.-S., Li, H.-H., Wang, H.-J., Zou, R.-S., Lu, X.-J., Wang, J., Nie, B.-B., Wu, J.-F., Li, S., Shan, B.-C., Wu, P.-F., Long, L.-H., Hu, Z.-L., Chen, J.-G., & Wang, F. (2023). Microglia-dependent excessive synaptic pruning leads to cortical underconnectivity and behavioral abnormality following chronic social defeat stress in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 109, 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2022.12.019.

[38] Dheer, A., Bosco, D. B., Zheng, J., Wang, L., Zhao, S., Haruwaka, K., Yi, M.-H., Barath, A., Tian, D.-S., & Wu, L.-J. (2024). Chemogenetic approaches reveal dual functions of microglia in seizures. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 115, 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.11.002.

[39] Taylor, R. A., Hammond, M. D., Ai, Y., & Sansing, L. H. (2015). Abstract 114: CX3CR1-null Microglia Fail to Transition to an M2 Phenotype after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke, 46(suppl_1). https://doi.org/10.1161/str.46.suppl_1.114.