Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by the accumulation of phospholipid hydroperoxides. Its core mechanisms involve dysregulation of iron metabolism and failure of the glutathione-GPX4 antioxidant axis. This process exhibits dual roles in human diseases, demonstrating therapeutic potential by eliminating malignant cells in cancer, while contributing to pathological damage in neurodegenerative disorders. This overview summarizes the core mechanisms, dual disease relevance, and the expanding landscape of therapeutic targets for modulating ferroptosis.

Table of Contents

1. What is Ferroptosis?

2. Mechanisms and Pathways of Ferroptosis

3. Why is ferroptosis different from apoptosis?

4. Ferroptosis in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases

5. Biomarkers of Ferroptosis

6. Target Ferroptosis for therapy

01 What is Ferroptosis?

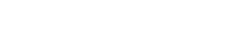

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent, regulated form of cell death characterized by phospholipid peroxidation, distinct from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy in both biochemical mechanisms and morphological features[1]. The process is initiated when intracellular iron accumulates to a level that catalyzes the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within membrane phospholipids, ultimately compromising membrane integrity. First identified in 2003 and formally named in 2012, ferroptosis was recognized by the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death as a distinct form of regulated cell death in 2018[2]. Physiologically, ferroptosis is implicated in the regulation of tissue homeostasis and a spectrum of biological processes, including development, aging, and immunity. Its dysregulation is increasingly linked to pathological conditions such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, highlighting its broad biomedical significance[3].

Fig. 1 General Timeline for Ferroptosis[4].

02 Mechanisms and Pathways of Ferroptosis

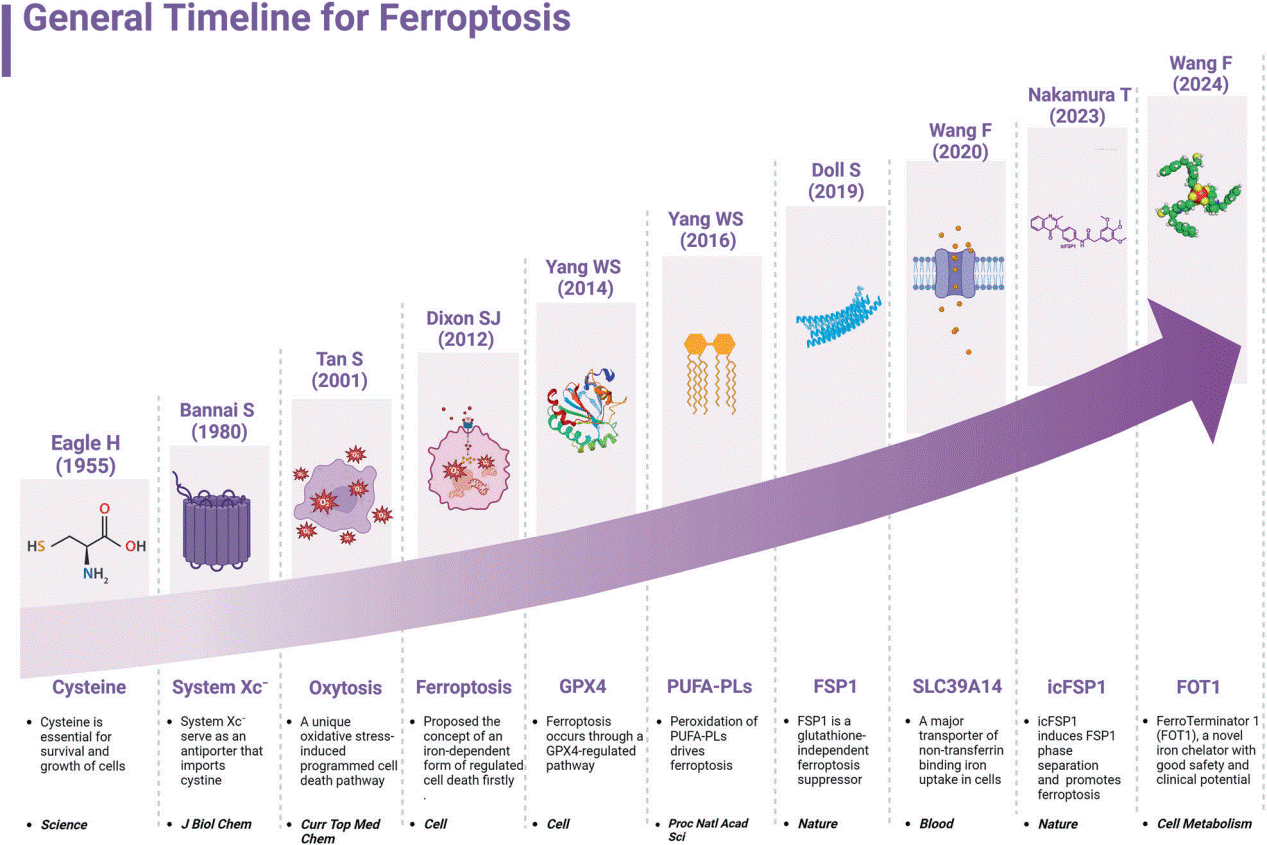

The initiation and execution of ferroptosis are governed by interconnected metabolic pathways involving iron homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and cellular antioxidant machinery[5].

2.1 Iron Homeostasis Regulation

The susceptibility to ferroptosis is critically governed by the precise regulation of intracellular iron homeostasis, particularly the labile iron pool (LIP). Cellular iron uptake, primarily via transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) mediated endocytosis and subsequent reduction to Fe²⁺ by STEAP3, increases the LIP and promotes ferroptosis by fueling the iron-dependent Fenton reaction, which generates lipid peroxidation-driving hydroxyl radicals. Conversely, iron sequestration within ferritin or export via ferroportin (FPN) diminishes the LIP and confers protection[4]. Furthermore, processes like NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy liberate stored iron, thereby amplifying ferroptotic sensitivity[6]. Thus, the net cellular iron balance, orchestrated by uptake, storage, export, and recycling pathways, directly determines ferroptotic vulnerability.

2.2 Lipid Metabolism and Peroxidation

The execution of ferroptosis is fundamentally driven by the process of ferroptosis lipid peroxidation, an iron-dependent peroxidation of membrane phospholipids. This pathway is critically regulated by the enzymatic axis comprising ACSL4 ferroptosis and LPCAT3 ferroptosis promotion. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) activates PUFAs, while lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) incorporates them into phospholipids, thereby creating peroxidation-susceptible membrane substrates[7]. The lethal accumulation of these lipid peroxides represents the core biochemical event in ferroptosis[8]. Therefore, the causal relationship between lipid peroxidation and ferroptosisis unequivocal, where peroxidation directly mediates the loss of membrane integrity and cell death.

2.3 Antioxidant Defense Pathways

System Xc⁻: The system Xc⁻ is a heterodimeric amino acid transporter complex central to cellular redox homeostasis.The primary physiological role of system Xc⁻ is to supply cells with cystine, which is rapidly reduced to cysteine inside the cell. Cysteine serves as the rate-limiting precursor for the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), a major intracellular antioxidant. By sustaining intracellular GSH pools, system Xc⁻ activity is crucial for counteracting oxidative stress and for preventing iron-dependent, lipid peroxidation-driven cell death, with the SLC7A11 ferroptosis link being well-established.

Glutathione Peroxidase 4(GPX4): GPX4 is a selenoprotein that catalyzes the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) to non-toxic lipid alcohols (LOH), thereby preventing the accumulation of lethal lipid peroxides[9]. Utilizing GSH as an essential cofactor, GPX4 neutralizes peroxidized phospholipids integrated into cellular membranes and lipoproteins. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of GPX4 or GSH depletion triggers ferroptosis, underscoring its non-redundant role in cellular survival. Consequently, GPX4 expression and activity are tightly linked to ferroptosis sensitivity in diverse physiological and pathological contexts[10].

FSP1-CoQ10 Pathway: Studies have identified FSP1 (ferroptosis suppressor protein 1) as a key independent suppressor of ferroptosis. FSP1, formerly known as AIFM2, functions as an NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase that catalyzes the regeneration of reduced coenzyme Q10 (CoQH₂) from its oxidized form. Located at the plasma membrane via N-terminal myristoylation, FSP1-generated CoQH₂ acts as a lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidant, effectively scavenging lipid peroxyl radicals without relying on GSH[11]. This GPX4-independent mechanism highlights FSP1 as a critical therapeutic target, especially in cancers resistant to GPX4 inhibition.

Fig. 2 Mechanisms of ferroptosis[5].

03 Why is ferroptosis different from apoptosis?

Ferroptosis and apoptosis are two distinct forms of regulated cell death with fundamentally different mechanisms, morphological features, and immunological consequences. The table below summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1. Ferroptosis vs Apoptosis: A Comparative Summary

|

Feature |

Apoptosis |

Ferroptosis |

|

Primary Triggers |

Death receptor activation, DNA damage, developmental cues |

GPX4 inhibition, glutathione depletion, iron overload, lipid peroxidation inducer |

|

Core Biochemical Events |

Caspase activation, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), cytochrome c release |

Iron-dependent phospholipid peroxidation via Fenton reaction, inactivation of GPX4 antioxidant defense |

|

Key Regulators |

Caspases, Bcl-2 protein family |

GPX4, system Xc-, ACSL4, iron |

|

Morphological Hallmarks |

Cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, nuclear fragmentation, apoptotic bodies |

Mitochondrial shrinkage with reduced, intact nucleus, plasma membrane rupture |

|

Immunological Outcome |

Immunologically silent due to rapid phagocytosis |

Pro-inflammatory due to release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) |

Apoptosis is characterized by caspase activation leading to organized cellular dismantling, including chromatin condensation and formation of apoptotic bodies that are efficiently cleared by phagocytes, preventing inflammation[12]. In contrast, ferroptosis is driven by iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides, resulting from GPX4 inactivation or glutathione depletion. This process causes mitochondrial shrinkage and rupture of the plasma membrane, leading to the passive release of intracellular contents that trigger an inflammatory response[13].

Despite their distinct pathways, crosstalk exists between apoptosis and ferroptosis. Shared regulators like p53 can modulate both processes, and under certain conditions, cells may exhibit characteristics of both death modalities[14].

04 Ferroptosis in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Ferroptosis plays a context-dependent role in human diseases, acting as a double-edged sword in cancer and contributing to the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative conditions.

4.1 The Dual Role of Ferroptosis in Cancer

The relationship between ferroptosis and cancer is complex and paradoxical. On one hand, ferroptosis can function as a potent tumor suppressor mechanism. Many cancer cells demonstrate heightened sensitivity to ferroptosis due to their elevated iron demand, active lipid metabolism, and altered redox balance. This metabolic profile makes them vulnerable to ferroptosis induction, providing a promising therapeutic avenue for eliminating aggressive cancer cell populations that are refractory to conventional apoptosis-inducing therapies. Furthermore, ferroptosis inducers can synergize with immunotherapies by enhancing antigen presentation and activating anti-tumor immunity. This synergy is partly mediated by the release of DAMPs from ferroptotic cells, which can stimulate immune responses within the tumor microenvironment[3].

Conversely, certain cancer cells can upregulate defense pathways to survive in the face of ferroptotic stress, highlighting the adaptive nature of cancer progression. Key adaptive mechanisms include the upregulation of GPX4, the FSP1, and the system Xc⁻. This adaptive response underscores ferroptosis as a double-edged sword, where its induction can be therapeutically beneficial, but its inadvertent inhibition in the tumor microenvironment might potentially support cancer cell survival under certain conditions .

4.2 Ferroptosis in Neurodegenerative Diseases

In contrast to its therapeutic potential in oncology, ferroptosis is increasingly implicated as a pathogenic mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases[15]. The brain's high metabolic demand, abundance of PUFAs in neuronal membranes, and relatively weak antioxidant defenses collectively heighten its susceptibility to ferroptotic damage. Substantial evidence links this process to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), with iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation consistently observed in affected brain regions. The pathological hallmarks of these diseases, including protein aggregates, often co-localize with markers of ferroptosis. A detrimental cycle involving iron dysregulation, glutathione depletion, and uncontrolled lipid peroxidation contributes to neuronal loss. Notably, ferroptosis inhibitors such as ferrostatin-1(fer-1) and liproxstatin-1 demonstrate neuroprotective effects in experimental models, preserving cognitive and motor functions and highlighting the therapeutic potential of this pathway[16].

05 Biomarkers of Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by lipid peroxidation. Its identification relies on a panel of biomarkers spanning morphological, biochemical, genetic, and protein-level changes[5, 17]. These markers are crucial for experimental verification and potential clinical translation.

5.1 Morphological Biomarkers

Ferroptotic cells exhibit distinct necrotic-like morphology under microscopy. Key features include:

Cellular Morphology: Cell swelling and plasma membrane rupture, absent in apoptosis.

Mitochondrial Alterations: The most characteristic feature is mitochondrial shrinkage, increased membrane density, and reduction or disappearance of cristae, observable via transmission electron microscopy.

Nucleus: The nucleus remains intact without chromatin condensation, distinguishing it from apoptosis.

Immune Infiltration: Tissue sections may show immune cell infiltration, indicating associated inflammation.

5.2 Biochemical Biomarkers

Core biochemical, genetic/transcriptional, and protein-related events are definitive biomarkers for ferroptosis, as summarized below:

Table 2. Summarizes the Primary Biomarkers Used to Confirm Ferroptosis[18]

|

Category |

Key Biomarker |

Change |

Detection Method |

|

Biochemical |

Lipid Peroxidation |

Increase |

C11-BODIPY , Assay Kits |

|

Intracellular Fe²⁺ |

Increase |

FerroOrange, Iron Assay Kit |

|

|

GSH Level |

Decrease |

GSH/GSSG Assay |

|

|

GPX4 Protein/Activity |

Decrease |

Western Blot , Activity Assay |

|

|

Protein |

ACSL4 Protein |

Increase |

Western Blot, IHC |

|

TFRC Protein |

Increase |

Western Blot, Flow Cytometry |

|

|

Genetic |

PTGS2 mRNA |

Increase |

qPCR, RNA-seq |

|

CHAC1 mRNA |

Increase |

qPCR |

06 Target Ferroptosis for therapy

Modulating ferroptosis presents a promising therapeutic strategy for a range of diseases, primarily through two approaches: inducing ferroptosis to kill cancer cells or inhibiting it to protect against degenerative diseases.

Inducing Ferroptosis for Cancer Therapy

Therapeutic strategies focus on key nodes in the ferroptosis pathway. Inhibiting system Xc⁻ depletes glutathione, while directly targeting GPX4 disables the primary phospholipid peroxidase defense[19]. Other strategies include increasing iron availability or targeting parallel defense systems like FSP1[20]. The integration of ferroptosis inducers with conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy is an area of active investigation, showing potential to overcome treatment resistance[21].

Table 3. Key Therapeutic Targets for Inducing Ferroptosis in Cancer

|

Pathway |

Representative Agents |

Mechanism of Action |

|

System Xc⁻ |

Erastin, Sulfasalazine |

Inhibits cystine uptake, depleting GSH |

|

GPX4 |

RSL3, ML162 |

inhibits GPX4 activity, leading to LPO accumulation |

|

FSP1 |

iFSP1 |

Inhibits FSP1, blocking CoQH2-mediated antioxidant defense |

|

Iron Metabolism |

Ironomycin, Lapatinib |

Increases intracellular labile iron pool, amplifying lipid peroxidation |

Inhibiting Ferroptosis for Organ Protection

In diseases driven by excessive ferroptosis, inhibitors are being developed. Iron chelators reduce the catalytic iron source[22]. Lipophilic antioxidants, such as the fer-1 ferroptosis inhibitor , scavenge lipid radicals to halt the peroxidation chain reaction. Additionally, activating endogenous defense pathways represents another protective strategy[23].

Table 4. Key Therapeutic Targets and Agents for Inhibiting Ferroptosis

|

Mechanism |

Representative Agents |

Protective Action |

|

Iron Chelation |

Deferoxamine, Deferiprone |

Reduces catalytic iron, suppressing ROS generation via Fenton reaction |

|

Lipid Antioxidant |

fer-1, Liproxstatin-1, Vitamin E |

Neutralizes lipid radicals, blocking membrane damage |

|

GPX4 Enhancement |

Selenium, Selenocysteine |

Boosts synthesis or activity of GPX4 to reduce lipid hydroperoxides |

|

FSP1Pathway |

FSP1 inducers |

Regenerates ubiquinol as a radical-trapping antioxidant |

Recommended Elabscience® Ferroptosis Assay Kits

Table 5. Ferroptosis Assay Kits

|

Cat. No. |

Product Name |

|

E-BC-F003 |

Lipid Peroxide (LPO) Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K814-M |

Enhanced Cell Malondialdehyde (MDA) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-F077 |

Lipoxygenase (LOX) Activity Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K138-F |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Green) |

|

E-BC-F005 |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Red) |

|

E-BC-F022 |

Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein-1 (FSP-1) Activity Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-D008 |

Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein-1 (FSP-1) Inhibitor Screening Kit |

|

E-BC-F066 |

Cystine Uptake Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K097-M |

Total Glutathione (T-GSH)/Oxidized Glutathione (GSSG) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K809-M |

Cell Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX) Activity Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K883-M |

Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4) Activity Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K903-M |

Glutamic Acid (Glu) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K030-M |

Reduced Glutathione (GSH) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K096-M |

Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) Activity Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-F101 |

Cell Ferrous Iron (Fe2+ ) Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K880-M |

Cell Total Iron Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K881-M |

Cell Ferrous Iron Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K773-M |

Ferrous Iron Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K794-M |

Squalene Synthase (SQS) Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K771-M |

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Cytotoxicity Colorimetric Assay Kit |

References:

[1] Dixon, S.J., et al., Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell, 2012. 149(5): p. 1060-72.

[2] Galluzzi, L., et al., Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ, 2018. 25(3): p. 486-541.

[3] Stockwell, B.R., et al., Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell, 2017. 171(2): p. 273-285.

[4] Ru, Q., et al., Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2024. 9(1): p. 271.

[5] Stockwell, B.R., Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell, 2022. 185(14): p. 2401-2421.

[6] Gao, M., et al., Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res, 2016. 26(9): p. 1021-32.

[7] Yang, W.S., et al., Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(34): p. E4966-75.

[8] Imai, H., et al., Lipid Peroxidation-Dependent Cell Death Regulated by GPx4 and Ferroptosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2017. 403: p. 143-170.

[9] Maiorino, M., M. Conrad, and F. Ursini, GPx4, Lipid Peroxidation, and Cell Death: Discoveries, Rediscoveries, and Open Issues. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018. 29(1): p. 61-74.

[10] Ursini, F., GPx4 is the controller of a specific form of programmed cell death executed by lipid peroxidation products. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2018. 124: p. 559-560.

[11] Wenzel, S.E., et al., PEBP1 Wardens Ferroptosis by Enabling Lipoxygenase Generation of Lipid Death Signals. Cell, 2017. 171(3): p. 628-641.e26.

[12] Ashkenazi, A. and G. Salvesen, Regulated cell death: signaling and mechanisms. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2014. 30: p. 337-56.

[13] Sarhan, M., et al., Origin and Consequences of Necroinflammation. Physiol Rev, 2018. 98(2): p. 727-780.

[14] Ranjan, A. and T. Iwakuma, Non-Canonical Cell Death Induced by p53. Int J Mol Sci, 2016. 17(12).

[15] Wu, J.R., Q.Z. Tuo, and P. Lei, Ferroptosis, a Recent Defined Form of Critical Cell Death in Neurological Disorders. J Mol Neurosci, 2018. 66(2): p. 197-206.

[16] Mahoney-Sánchez, L., et al., Ferroptosis and its potential role in the physiopathology of Parkinson's Disease. Prog Neurobiol, 2021. 196: p. 101890.

[17] Chen, X., et al., Characteristics and Biomarkers of Ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 9: p. 637162.

[18] Chen, Z., et al., The application of approaches in detecting ferroptosis. Heliyon, 2024. 10(1): p. e23507.

[19] Jin, X., et al., Ferroptosis: Emerging mechanisms, biological function, and therapeutic potential in cancer and inflammation. Cell Death Discov, 2024. 10(1): p. 45.

[20] Gong, J., et al., TRIM21-Promoted FSP1 Plasma Membrane Translocation Confers Ferroptosis Resistance in Human Cancers. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2023. 10(29): p. e2302318.

[21] Ma, W., et al., Mechanisms of ferroptosis and targeted therapeutic approaches in urological malignancies. Cell Death Discov, 2024. 10(1): p. 432.

[22] Deng, L., W. Tian, and L. Luo, Application of natural products in regulating ferroptosis in human diseases. Phytomedicine, 2024. 128: p. 155384.

[23] Bell, H.N., B.R. Stockwell, and W. Zou, Ironing out the role of ferroptosis in immunity. Immunity, 2024. 57(5): p. 941-956.