Mitochondria serve as central hubs for bioenergetics, metabolite biosynthesis, and cellular signaling. Their dysfunction is intimately linked to the pathogenesis of breast cancer, driving tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to therapies. Consequently, precisely assessing and therapeutically targeting mitochondrial function have become significant frontiers in oncology research and treatment development.

In this context, we outline the rewired metabolic pathways and bioenergetic adaptations in breast cancer cells, discuss the pivotal role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in disease progression, and highlight emerging strategies for mitochondria-targeted drug delivery and treatment.

Table of Contents

1. How do mitochondria affect breast cancer?

2. Mitochondrial dysfunction in breast cancer

3. Comparison between normal and cancerous breast cell mitochondria

4. Significance of oxidative stress caused by mitochondria in breast cancer

5. The effect of mitochondrial-targeted drugs on breast cancer treatment

01 How do mitochondria affect breast cancer?

Mitochondria are central orchestrators of cellular fate in breast cancer (BC), extending far beyond their role as cellular powerhouses. Their influence manifests through metabolic reprogramming, dynamic adaptation, and intercellular communication, all of which fuel tumor progression and therapy resistance[1].

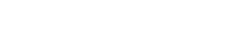

1.1 Metabolic Reprogramming and Bioenergetic Adaptations

Breast cancer cells exhibit significant metabolic plasticity[2]. While the Warburg effect highlights a glycolytic phenotype, these cells frequently co-opt mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to meet the substantial bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands of proliferation and survival[3]. This reprogramming of mitochondrial bioenergetics is a hallmark of cancer. Mitochondrial ATP production efficiency, mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS levels are critical for maintaining this adaptive balance. For instance. oncogenic signaling directly targets mitochondrial enzymes; the HER2 pathway can phosphorylate mitochondrial creatine kinase 1, enhancing energy shuttling and promoting proliferation in HER2+ BC[4]. Beyond this direct regulation of energy metabolism, mitochondrial anabolic functions are also co-opted. Notably, glycine dependency emerges as a critical metabolic hallmark in aggressive breast cancer. Increased expression of genes involved in mitochondrial glycine biosynthesis is linked to higher proliferation rates and mortality, with HER2-positive and luminal B subtypes often showing elevated reliance on this pathway[5]. This reprogramming positions mitochondrial glycine synthesis as a potential therapeutic target alongside energy metabolism, highlighting the dual role of mitochondria in supporting rapid cancer cell proliferation through both bioenergetic and biosynthetic adaptations.

Fig. 1 Mitochondrial alterations in cancer cell[2].

1.2 Mitochondrial Dynamics and Intercellular Transfer

In breast cancer, dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics, often characterized by reduced fusion, is associated with elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, resistance to apoptosis, and enhanced metastatic potential[6]. Intracellular trafficking directs mitochondria to subcellular regions with high energy demands, including the leading edge of migrating cells, thereby supporting invasion and metastasis[7]. A particularly aggressive mechanism involves the intercellular transfer of functional mitochondria from stromal cells to cancer cells via tunneling nanotubes, enhancing the recipient cell's mitochondrial ATP generation capacity and conferring resistance to chemotherapy. This transfer supplies functional mitochondria to compromised recipient cells, promoting tumor survival, proliferation, and drug resistance, ultimately contributing to tumor adaptation and heterogeneity.

02 Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Breast Cancer

Breast carcinogenesis and progression are closely linked to the state of mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by failures in quality control, genomic instability, and epigenetic dysregulation.

2.1 Impairment of Mitochondrial Quality Control and Homeostasis

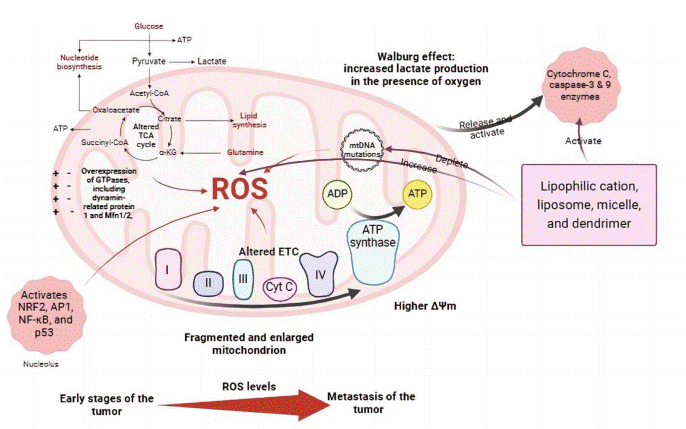

Mitochondrial dysfunction in BC encompasses a breakdown in the core systems maintaining organelle integrity. This includes imbalances in mitochondrial quality control (MQC) mechanisms (biogenesis, fusion/fission dynamics, and mitophagy) leading to the accumulation of damaged organelles[8]. Concurrently, disturbances in OXPHOS, ATP synthesis, calcium buffering, and metabolic signaling create a cellular environment conducive to malignancy. This dysfunctional state often manifests as metabolic dysregulation, excessive ROS production, and disrupted ion homeostasis, which collectively drive disease progression.

2.2 mtDNA Mutations and Mitoepigenetic Alterations

Somatic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are highly prevalent in breast tumors[9]. These mutations, particularly in genes encoding electron transport chain components like Complex I, can disrupt OXPHOS, reduce mitochondrial ATP synthesis, and lead to excessive mitochondrial ROS production[10]. The ensuing oxidative stress damages both mtDNA and nuclear DNA, fostering a vicious cycle of genomic instability and activating pro-survival pathways. Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction is not merely a passenger but can be a causal factor in cancer development. For instance, intra-mitochondrial Src kinase (mtSrc) activity is elevated in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where it phosphorylates mitochondrial proteins, impairing mtDNA replication and further exacerbating mitochondrial defects, thereby increasing cellular aggressiveness[11]. This underscores the critical interplay between mitochondria and cancer cells.

Fig. 2 Dysfunction of mitochondria in tumors[8].

03 Comparison Between Normal and Cancerous Breast Cell Mitochondria

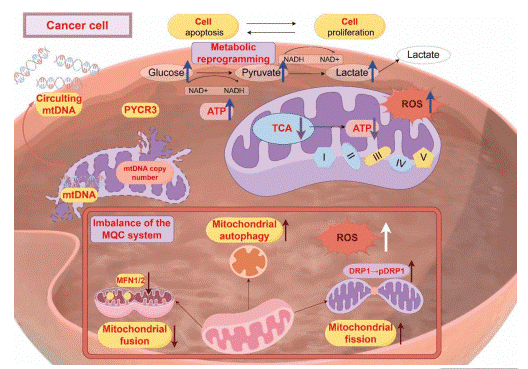

Significant morphological and functional distinctions exist between the mitochondria of normal breast epithelial cells and their cancerous counterparts. Normal cells rely on efficient OXPHOS for energy production, maintaining a well-coupled system for mitochondria ATP generation[7, 12].

In contrast, breast cancer cells adapt their mitochondrial physiology to support rapid proliferation and survival under stress[1]. This often involves a rewiring of mitochondrial bioenergetics, with a shift toward aerobic glycolysis and altered use of mitochondrial substrates. Structurally, cancer mitochondria frequently display a fragmented morphology due to imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics. A key difference lies in the regulation of the mitochondrial membrane potential. While crucial for ATP synthesis, its dysregulation in cancer cells can suppress apoptosis[13]. Functionally, studies using transmitochondrial cybrids have demonstrated that breast cancer cells and their mitochondria exhibit reduced oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and lower ATP synthesis capacity compared to normal cells, confirming inherent defects in OXPHOS[14]. This dysfunctional state contributes to higher baseline oxidative stress in cancer compared to normal tissue.

Fig. 3 Mitochondrial dynamics in normal and cancer cells[15].

04 Significance of Oxidative Stress Caused by Mitochondria in Breast Cancer

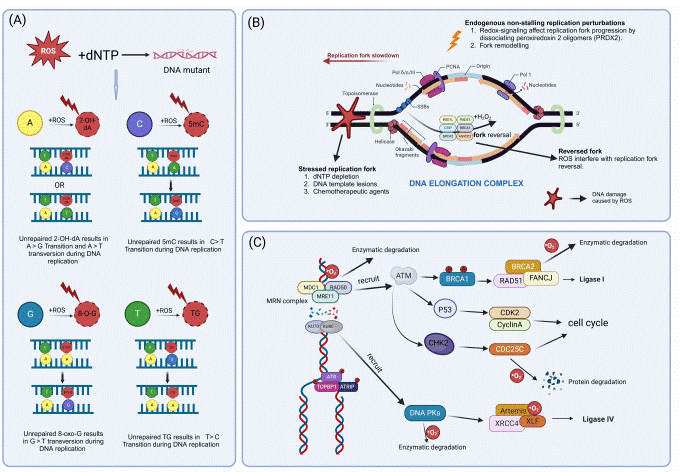

As the primary endogenous source of ROS, mitochondria-generated oxidative stress is a potent driver of breast cancer progression. ROS are mainly generated at Complexes I and III of the electron transport chain, and an imbalance between their production and antioxidant defenses creates a state of chronic oxidative stress. The relationship between mitochondria and oxidative stress is synergistic. Mitochondrial dysfunction, through mtDNA mutations or impaired ETC function, exacerbates mitochondrial ROS production. Oxidative stress, in turn, induces pro-tumorigenic effects such as oxidative DNA damage (e.g., 8-OHdG formation), which fosters genomic instability, activation of pro-survival pathways, and promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to facilitate invasion and metastasis. Furthermore, mitochondrial ROS can directly inhibit DNA repair machinery, creating a vicious cycle of mutation accumulation[16]. Interestingly, the cellular NAD+/NADH redox balance, which is regulated by mitochondrial function, plays a critical role in controlling signaling pathways like mTOR, influencing tumor growth and metastatic potential[17]. Therapeutic normalization of this balance has been shown to inhibit metastasis in preclinical models.

Fig. 4 Excessive ROS lead to DNA damage[16].

05 The effect of mitochondrial-targeted drugs on breast cancer treatment

Given the critical role of mitochondrial dysfunction in BC, targeting mitochondrial pathways has emerged as a viable therapeutic strategy. Current strategies focus on exploiting mitochondrial vulnerabilities through direct inhibitors and advanced drug delivery systems.

5.1. Mitochondrial Inhibitors

Pharmacological agents designed to disrupt specific mitochondrial functions are under active investigation. These include direct inhibitors of OXPHOS complexes and indirect strategies targeting key regulatory factors. For instance,the transcription factor BACH1, frequently overexpressed in TNBC, represses electron transport chain (ETC) genes. Its depletion sensitizes tumors to ETC inhibitors like metformin, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting such regulators[18]. Separately, activation of mitochondrial caseinolytic protease P (ClpP) induced the uncontrolled degradation of respiratory chain proteins, causing irreversible mitochondrial dysfunction and demonstrating efficacy in preclinical BC models[19]. Beyond direct mitochondrial targeting, research on vitamin D and breast cancer has revealed the potential of vitamin D as a preventive and adjuvant therapeutic agent. While the precise mechanisms are under investigation, it is hypothesized that vitamin D may help modulate mitochondrial redox homeostasis, potentially interrupting the vicious cycle of mitochondria and oxidative stress by enhancing antioxidant defenses or stabilizing mitochondrial function[20]. Clinically, higher serum vitamin D levels have been correlated with improved survival outcomes and reduced risk of metastasis in breast cancer patients[21].

5.2 Mitochondria-Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

To improve specificity, significant efforts are directed toward mitochondria-targeted drug delivery systems. These systems conjugate therapeutic agents to mitochondria-homing moieties, such as triphenylphosphonium (TPP+) cations or mitochondria-penetrating peptides[22]. This approach ensures high intramitochondrial accumulation of the drug, directly targeting the core of mitochondrial bioenergetics and apoptotic signaling in mitochondria and cancer cells. For instance, mitochondria-targeted liposomes delivering copper complexes can disrupt the mitochondrial unfolded protein response, effectively inducing apoptosis even in drug-resistant subtypes. These strategies aim to maximize efficacy while minimizing off-target effects.

Recommended Elabscience® Mitochondrial Function Assay Kits

Table 1. Assay Kits for Mitochondrial Functional Research

|

Cat. No. |

Product Name |

|

E-BC-F064 |

Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP) Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-F070 |

Enhanced Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-F300 |

ATP Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K774-M |

ATP Colorimetric Assay Kit (Enzyme Method) |

|

E-BC-F201 |

Enhanced ATP Chemiluminescence Assay Kit |

|

E-CK-A301 |

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (with JC-1) |

|

E-BC-F078 |

Mitochondrial Stress Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K784-M |

Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K138-F |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Green) |

|

E-BC-F008 |

Mitochondrial Superoxide Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-F005 |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Red) |

|

E-BC-K804-M |

NAD+/NADH Colorimetric Assay Kit (WST-8) |

References:

[1] Avagliano, A., et al., Mitochondrial Flexibility of Breast Cancers: A Growth Advantage and a Therapeutic Opportunity. Cells, 2019. 8(5).

[2] Ghazizadeh, Y., et al., Exploring the Potential of Mitochondria-Targeted Drug Delivery for Enhanced Breast Cancer Therapy. Int J Breast Cancer, 2025. 2025: p. 3013009.

[3] Yan, Y., et al., Mitochondrial inhibitors: a New Horizon in Breast Cancer Therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2024. Volume 15 - 2024.

[4] Czegle, I., et al., The Role of Genetic Mutations in Mitochondrial-Driven Cancer Growth in Selected Tumors: Breast and Gynecological Malignancies. Life, 2023. 13(4): p. 996.

[5] Jain, M., et al., Metabolite Profiling Identifies a Key Role for Glycine in Rapid Cancer Cell Proliferation. Science, 2012. 336(6084): p. 1040-4.

[6] Sehrawat, A., et al., Inhibition of Mitochondrial Fusion is an Early and Critical Event in Breast Cancer Cell Apoptosis by Dietary Chemopreventative Benzyl isothiocyanate. Mitochondrion, 2016. 30: p. 67-77.

[7] Libring, S., E.D. Berestesky, and C.A. Reinhart-King, The Movement of Mitochondria in Breast Cancer: Internal Motility and Intercellular Transfer of Mitochondria. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis, 2024. 41(5): p. 567-587.

[8] Huang, A., et al.,A Review of the Pathogenesis of Mitochondria in Breast Cancer and Progress of Targeting Mitochondria for Breast Cancer Treatment. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2025. 23(1): p. 70.

[9] Pérez-Amado, C.J., et al., Mitochondrial DNA Mutation Analysis in Breast Cancer: Shifting From Germline Heteroplasmy Toward Homoplasmy in Tumors. Frontiers in Oncology, 2020. 10.

[10] McMahon, S. and T. LaFramboise, Mutational patterns in the breast cancer mitochondrial genome, with clinical correlates. Carcinogenesis, 2014. 35(5): p. 1046-54.

[11] Yadav, N. and D. Chandra, Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and Breast Tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013. 1836(2): p. 336-44.

[12] Zakic, T., et al., Breast Cancer: Mitochondria-Centered Metabolic Alterations in Tumor and Associated Adipose Tissue. Cells, 2024. 13(2).

[13] Mukherjee, S., et al., Targeting Mitochondria as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy Against Chemoresistance in Cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2023. 160: p. 114398.

[14] Chen, K., et al., Mitochondrial Mutations and Mitoepigenetics: Focus on Regulation of Oxidative Stress-Induced Responses in Breast Cancers. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2022. 83: p. 556-569.

[15] Ruidas, B., Mitochondrial Dynamics in Breast Cancer Metastasis: From Metabolic Drivers to Therapeutic Targets. Oncology Advances, 2025. 3(1): p. 39-49.

[16] Dong, R., et al., Role of Oxidative Stress in the Occurrence, Development, and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Antioxidants (Basel), 2025. 14(1).

[17] Mencalha, A., et al., Mapping Oxidative Changes in Breast Cancer: Understanding the Basic to Reach the Clinics. Anticancer Res, 2014. 34(3): p. 1127-40.

[18] Lee, J., et al., Effective Breast Cancer Combination Therapy Targeting BACH1 and Mitochondrial Metabolism. Nature, 2019. 568(7751): p. 254-258.

[19] Wedam, R., et al., Targeting Mitochondria with ClpP Agonists as a Novel Therapeutic Opportunity in Breast Cancer. Cancers, 2023. 15(7): p. 1936.

[20] Thabet, R.H., et al.,Vitamin D: an Essential Adjuvant Therapeutic Agent in Breast Cancer. J Int Med Res, 2022. 50(7): p. 3000605221113800.

[21] Karkeni, E., et al., Vitamin D Controls Tumor Growth and CD8+ T Cell Infiltration in Breast Cancer. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 1307.

[22] Tabish, T.A., et al., Mitochondria-Targeted Metal–Organic Frameworks for Cancer Treatment. Materials Today, 2023. 66: p. 302-320.