The advent of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has revolutionized cancer therapy, yet its efficacy remains limited to a subset of patients. While current immunothepies predominantly focus on harnessing neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells, the tumor microenvironment necessitates a coordinated immune response for effective tumor eradication. Natural Killer (NK) cells, cytotoxic innate lymphocytes renowned for their ability to spontaneously eliminate transformed cells, are emerging as pivotal players in antitumor immunity. Accumulating clinical evidence underscores the prognostic value of intratumoral NK cells and their contribution to immunotherapy response [1,2].

This review outlines the fundamental concepts, development, maturation, diverse functions, and underlying mechanisms of natural killer cells (NK cells). In addition, it expands the discussion to concisely address the roles, mechanisms, and relevant biomarkers of NK cells within the context of tumor immunity.

Table of Contents

1. What are natural killer cells?

2. Development and maturation of NK cells

3. Function of NK cells

4. How do natural killer cells work?

5. NK cells in cancer immunotherapy

6. Biomarkers related to natural killer cells

01 What are natural killer cells?

Natural killer cells (NK cells) represent a critical element of the innate immune system, serving as effector lymphocytes that constitute the first line of defense against pathogens and malignant cells [3,4]. These cells derive from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow and mature through a multi-step differentiation process involving common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) [6]. Since their discovery more than three decades ago, NK cells have been identified as large granular lymphocytes. In contrast to T and B lymphocytes, they do not undergo somatic recombination of T-cell receptor (TCR) or immunoglobulin genes, thereby classifying them as members of the innate immune system. Nevertheless, although primarily regarded as innate immune cells, NK cells display certain adaptive immunological traits, such as antigen-specific clonal expansion and the formation of long-lived memory cells, thereby blurring the traditional boundaries between innate and adaptive immunity [5].

02 Development and maturation of NK cells

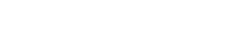

Natural killer cells (NK cells) exhibit cytotoxic functions comparable to those of CD8+ T cells in adaptive immunity, yet they lack CD3 and T-cell receptors (TCRs). Accounting for approximately 5%-10% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), NK cells circulate predominantly in the blood and are also present in the bone marrow and lymphoid tissues such as the spleen [7,8]. Like other innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), NK cells develop from common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) cells in the bone marrow (Fig. 1), with an average renewal cycle of about two weeks.

Fig. 1 Development and subgroups of NK cells. In bone marrow, NK cells develop from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) through common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) and NK cell precursors (NKPs), and then migrate to peripheral blood (cNK cells) or tissue (trNK cells) [3].

During their development, NK cells undergo an “education” process through interactions between inhibitory receptors bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules. This process licenses NK cells to distinguish and spare healthy self-cells [9,10]. Interestingly, tumor cells often downregulate or lose MHC-I expression to evade CD8+ T cell-mediated killing, a strategy that conversely enhances NK cell activation. Moreover, tumor cells express stress-induced ligands such as MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A/B (MICA/MICB), which further activate NK cells and support their potential as anticancer agents [11,12]. Unlicensed NK cells also contribute to immunity, for instance, by controlling murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection and targeting MHC-I+ cells [13].

NK cell survival and development is primarily regulated by cytokines (especially IL-2 and IL-15) and key transcription factors (Nfil3, Id2 and Tox for development, and EOMES and T-bet for maturation). The adaptor protein GAB3 is essential for IL-2 and IL-15 signaling, and its deficiency impairs NK cell expansion [14]. Targeting negative regulatory signaling represents a promising strategy to enhance NK cell antitumor function. For example, ablation of the cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS), which suppresses IL-15 signaling, has been shown to inhibit metastasis and synergize with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapy in vivo [15].

03 Function of NK cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are a vital component of the innate immune system, with diverse functions primarily exerted through cytotoxicity and cytokine production [16]. They play a critical role in the host’s defense against pathogens and tumors [1,2,3]. Specifically, NK cell function mainly includes the following:

Cytotoxic effect: One of the most prominent functions of NK cells is their potent cytotoxic capacity. They can recognize and lyse a variety of target cells, including virus-infected cells, tumor cells, and stressed cells, without prior sensitization or MHC restriction [17].

Cytokine and chemokine production: Beyond direct cytotoxicity, NK cells also serve as important immunoregulatory cells [16]. They are capable of producing a variety of cytokines and chemokines, thereby modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses.

Immunoregulatory effect: NK cells act not only as effector cells but also play a critical role in immunoregulation through bidirectional interactions with other immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and T cells. They can either restrict or amplify immune responses, contributing to the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Specifically, NK cells can inhibit adaptive immune responses by killing immature DCs, or promote DC maturation and function through the secretion of cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ). Additionally, NK cells can regulate the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of T cells, thereby influencing the magnitude and type of adaptive immune responses. Several studies have demonstrated that under specific conditions, NK cells can also exert the function of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by expressing MHC class II molecules and co-stimulatory molecules to activate T cells [16,18].

Memory function: Although NK cells are traditionally classified as innate immune cells, recent studies have revealed that they possess features of adaptive immunity, including the ability to mount memory-like responses against specific antigens. Upon re-exposure to the same pathogen, these memory-like NK cells can respond more rapidly and efficiently, a property that blurs the traditional boundary between innate and adaptive immunity [19,20].

Tissue-specific functions: NK cells are widely distributed in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. NK cell subsets in different tissues may exhibit unique phenotypes and functions to adapt to the demands of the local microenvironment. For instance, NK cells in the liver play a role in immune surveillance against liver tumors and viral infections [21].

04 How do natural killer cells work?

Natural Killer (NK) cells are a vital component of the innate immune system. Their operational mechanisms involve complex processes of recognition, activation, effector functions, and interactions with other immune cells, all of which enable the effective elimination of pathogen-infected cells and tumor cells while maintaining immune homeostasis.

Activating and Inhibitory Recognition Mechanisms: NK cells distinguish between healthy and aberrant cells through a sophisticated balance of activating and inhibitory receptors expressed on their surface. Activating receptors, such as NKG2D, NKp30, NKp46, and NKp80, recognize stress-induced ligands on target cells, thereby triggering NK cell activation and cytotoxic responses. In contrast, inhibitory receptors, including killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and NKG2A, bind to MHC class I molecules constitutively expressed on healthy cells, thus preventing NK cell-mediated attack against self-tissues. The ultimate response of NK cells is determined by the integration of these opposing activating and inhibitory signals. This finely tuned regulatory mechanism ensures the efficient elimination of pathological cells while preserving the integrity of normal tissues [22].

Cytotoxic Mechanisms: Once activated, NK cells rapidly exert two primary effector functions: direct killing of target cells and secretion of various immunoregulatory molecules (e.g., cytokines, chemokines) [17].

The perforin-granzyme pathway represents one of the most dominant cytotoxic mechanisms employed by NK cells. When NK cells establish tight contact with target cells, an immunological synapse is formed, followed by the release of cytolytic granules. These granules contain perforin and granzymes (e.g., granzyme B), where perforin forms pores in the target cell membrane to facilitate the entry of granzymes into the target cell cytoplasm. Subsequently, granzymes activate the caspase cascade within the target cell, ultimately triggering target cell apoptosis [17].

In the death receptor pathway, NK cells express Fas ligand (FasL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) on their surface. These ligands can bind to corresponding death receptors (e.g., Fas receptor or TRAIL receptor) expressed on the target cell surface, thereby activating intracellular apoptotic signaling pathways and inducing programmed cell death of the target cell [23].

Immune regulatory mechanisms: Beyond direct cytotoxicity, NK cells modulate immune responses through cytokine and chemokine secretion. IFN-γ, a central effector cytokine, exerts broad antiviral and antitumor effects by activating macrophages and T cells, upregulating MHC class I expression, and skewing adaptive immunity toward a Th1 phenotype. NK cells also produce other immunomodulators, such as IL-10 and various chemokines, which help recruit additional immune cells to inflammatory sites and potentiate the overall immune response [20,21].

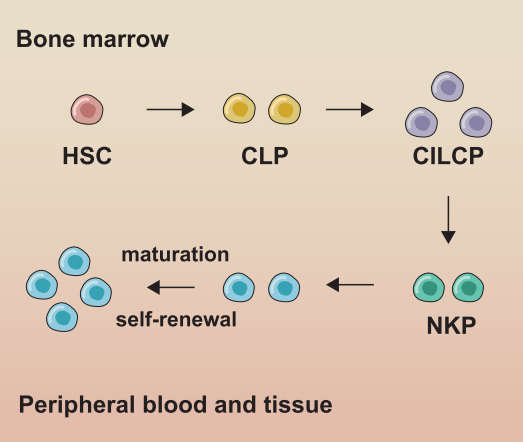

Fig. 2 NK cells were isolated from the spleen cells of C57BL/6 mice, Mouse spleen cells were co-stained before and after the sorting with APC Anti-Mouse CD3 Antibody[17A2] (E-AB-F1013E) and PE Anti-Mouse NK1.1 Antibody[PK136] (E-AB-F0987D), the result shows that the proportion of CD3-NK1.1+ cells before and after the sorting of mouse spleen cells were 4.2% and 95.1%, respectively.

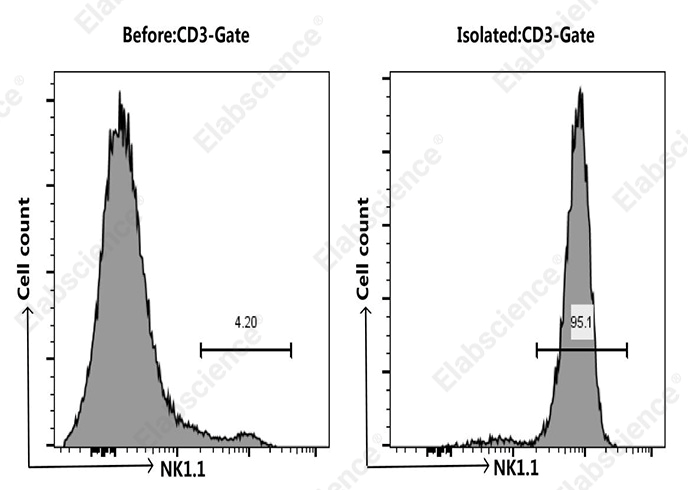

Fig. 3 NK cells were isolated from spleen cells of C57BL/6 mice and co-cultured with jurkat cells in a 1:1 ratio for 24 hours. After staining with CFSE (E-CK-A345) and DAPI (E-CK-A163), the killing effect of NK cells on Jurkat cells was verified. Compared with normal jurkat cells (left), after co-culture with NK cells for 24 hours (right), The mortality rate of jurkat cells increased from 3.93% to 24.41%.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table.1 Research Tools for NK cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Applications |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

APC |

E-AB-F1013E |

Detection of NK cells |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1136J |

|

|

NK1.1 |

PK136 |

PE |

E-AB-F0987D |

|

|

CD49b |

DX5 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1116C |

Table.2 Reagents for NK Cells Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

E-CK-A091 |

|

CFSE Cell Division Tracker Kit |

E-CK-A345 |

|

DAPI Reagent (25 μg/mL) |

E-CK-A163 |

|

Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit |

E-CK-A108 |

|

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

E-CK-A109 |

|

EasySort™-5 Magnet |

EC001 |

|

10×ACK Lysis Buffer |

E-CK-A105 |

|

Caspase 3/7 Activity Detection Substrate for Flow Cytometry |

E-CK-A483 |

|

Caspase 8 Activity Detection Substrate for Flow Cytometry |

E-CK-A488 |

|

Caspase 9 Activity Detection Substrate for Flow Cytometry |

E-CK-A489 |

05 NK cells in cancer immunotherapy

The therapeutic potential of natural killer (NK) cells in cancer immunotherapy represents a rapidly evolving field, driven by their intrinsic anti-tumor capabilities as well as advancements in genetic engineering and delivery strategies [24].

One primary strategy involves the adoptive transfer of activated NK cells [24]. These cells can be derived from multiple sources, including autologous (patient’s own) NK cells (Cancer Natural Killer Cells), peripheral blood-derived NK cells from healthy donors, umbilical cord blood (UCB) or placenta-derived NK cells, and clonal NK cell lines (e.g., NK-92) [25, 26, 27]. Ex vivo expansion and activation of these NK cells can significantly enhance their anti-tumor activity [25]. Notably, memory-like NK cells, generated via exposure to cytokines such as IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18, exhibit enhanced anti-tumor activity and persistence [27].

Genetic modification of NK cells constitutes a significant advancement in this field. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-NK cells are engineered to express a CAR that specifically recognizes tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), thereby improving their specificity and efficacy against cancer cells [1,24,25]. Compared to CAR T-cells, CAR-NK cells offer potential advantages, including a reduced risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), as well as “off-the-shelf” applicability, particularly when derived from allogeneic sources. Additionally, non-viral technologies are being explored for CAR-NK cell therapy to enhance safety and manufacturing scalability [28].

Another therapeutic avenue focuses on enhancing NK cell activity through cytokine stimulation and immune checkpoint blockade [24]. Specifically, cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-15 can promote NK cell proliferation and functional activation [24]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, traditionally used to enhance T cell responses, are also being investigated to overcome NK cell suppression in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Blocking inhibitory receptors on NK cells can unleash their cytotoxic potential against tumor cells [25]. Moreover, strategies involving bispecific or trispecific killer engagers (BiKEs/TriKEs) can bridge NK cells to tumor cells, facilitating targeted killing [27]. Additionally, Tanshinone IIA, a natural product, has been shown to enhance NK cell-mediated lysis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells by up-regulating UL16-binding protein 1 (ULBP1) and death receptor 5 (DR5).

Furthermore, novel delivery strategies are being developed to improve the therapeutic potency of adoptively transferred NK cells, especially for solid tumors. This includes the use of biomaterials and nanoparticles to overcome the suppressive TME and enhance NK cell infiltration and persistence. Exosomes derived from immune cells, including NK cells (Cancer Natural Killer Cells), are also emerging as promising tools for cancer therapy, capable of inducing tumor cell apoptosis and modulating immune responses [29].

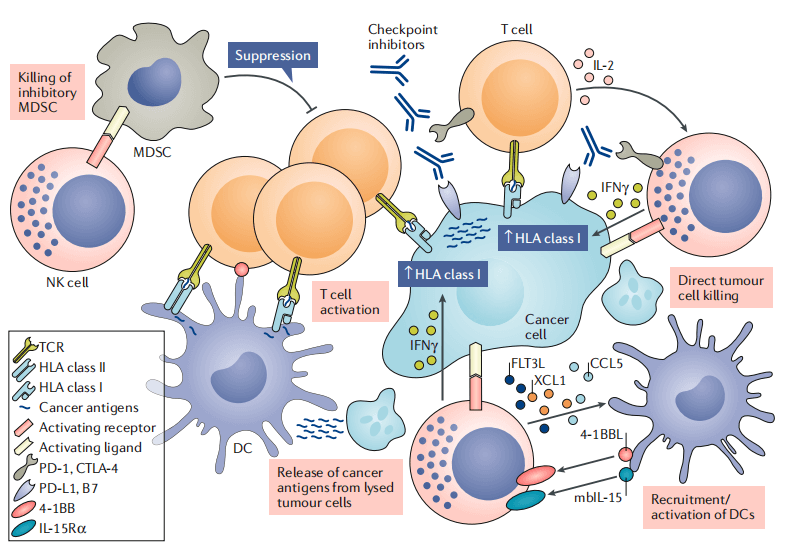

Fig. 4 Scenarios for interaction between NK cells and other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment [2].

06 Biomarkers related to natural killer cells

Natural Killer (NK) cells are identified and studied through a combination of surface receptors, intracellular proteins, and transcription factors. The table below summarizes the core biomarkers used to define human and mouse NK cells and their major functional subsets [3,5]:

Table.3 Biomarkers for Human NK Cells Research [3,5]

|

Category |

Biomarker |

Description and Function |

|

Defining Markers |

CD3- |

Negative for the T cell receptor complex. |

|

CD56+ |

Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM), primary marker for identifying human NK cells (CD56 Natural Killer Cells). |

|

|

CD16+ (FcγRIII) |

Mediates Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC), predominantly on CD56dim subset (CD16 NK Cells). |

|

|

Key Functional Receptors |

NKG2D (CD314) |

Activating receptor that recognizes stress-induced ligands on target cells. |

|

NCRs (NKp46, NKp30, NKp44) |

Natural Cytotoxicity Receptors, key activating receptors (NKp44 is induced upon activation). |

|

|

KIRs (e.g., CD158a/b) |

Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptors, mostly inhibitory, recognize MHC-I molecules. |

|

|

NKG2A/CD94 |

Inhibitory heterodimer that recognizes non-classical MHC-I molecules. |

|

|

Intracellular & Secreted |

Perforin |

Cytolytic protein that pores the target cell membrane. |

|

Granzymes (A, B, K, M) |

Serine proteases that induce apoptosis upon entering the target cell. |

|

|

IFN-γ |

Key immunomodulatory cytokine secreted upon activation. |

|

|

Transcription Factors |

T-bet (TBX21) |

Master regulator of NK cell development and function. |

|

Eomesodermin (Eomes) |

Critical for NK cell maturation and cytotoxicity, distinguishes NK from ILC1s. |

Table.4 Biomarkers for Mouse NK Cells Research [5,13]

|

Category |

Biomarker |

Function |

|

Defining Surface Markers |

CD49b (DX5), NKp46 (CD335), NK1.1 (CD161c) |

Used to define the NK cell population. |

|

Other Surface Receptors |

CD11b, CD16, CD94, CD122 (IL-2Rβ), NKG2D (CD314) |

Involved in activation, inhibition and adhesion. |

|

Intracellular Effector Molecules |

Perforin, Granzyme A, Granzyme B, Granzyme K |

Cytotoxic molecules stored in granules. |

|

Secreted Cytokines |

IFN-γ, TNF-α, CCL3 (MIP-1α) |

Key for NK cell effector functions. |

|

Transcription Factors |

T-bet, Eomes, Id2 |

Master regulators of NK cell development and function. |

Biomarkers of natural killer (NK) cells are essential for understanding their complex biological functions and their role in immune surveillance. From classical surface markers such as CD56 and CD16, to activating and inhibitory receptors like NKG2D and KIRs, as well as effector molecules including perforin, granzymes, and the cytokine IFN-γ, along with specific transcription factors and memory-like NK cell markers, these molecules collectively define the diversity and plasticity of NK cells. In the field of cancer immunotherapy, advancing research on these biomarkers will facilitate the development of more precise and effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies.

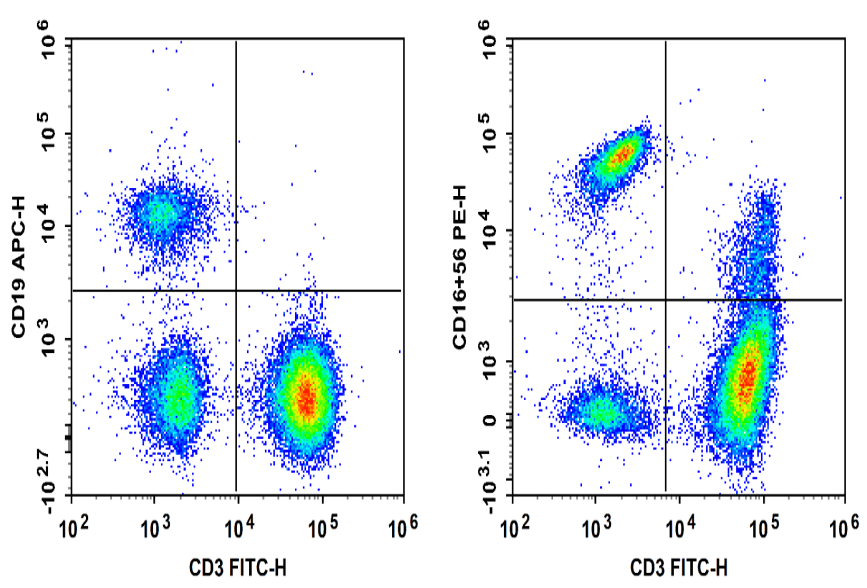

Fig. 5 Normal human peripheral blood cells are stained with FITC Anti-Human CD3, APC Anti-Human CD19, PE Anti-Human CD16 and PE Anti-Human CD56, followed by analysis via flow cytometry. NK cells exhibited the phenotype CD19- CD3- NK1.1+ and NKT cells exhibited the phenotype CD19- CD3+ NK1.1+.

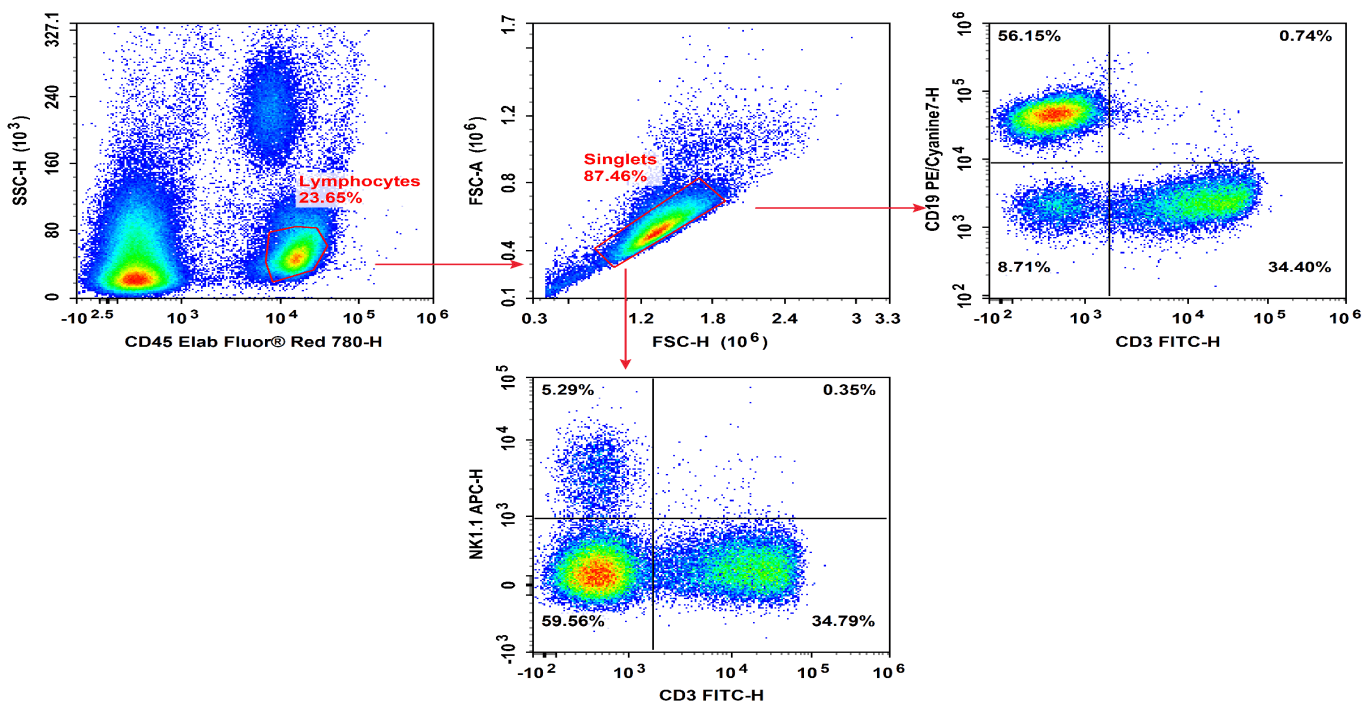

Fig. 6 Peripheral blood cells from C57BL/6 mice were treated with ACK Lysis Buffer to remove erythrocytes, then stained with Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Mouse CD45, FITC Anti-Mouse CD3, PE/Cyanine7 Anti-Mouse CD19, and APC Anti-Mouse NK1.1, followed by flow cytometric analysis. NK cells exhibited the phenotype CD45+ CD19- CD3- NK1.1+.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table. 5 Multicolor Panel for Flow Cytometric Analysis of NK cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Applications |

|

Human CD3 |

OKT-3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1001C |

Detection of Human NK Cells |

|

Human CD19 |

CB19 |

APC |

E-AB-F1004E |

|

|

Human CD16 |

3G8 |

PE |

E-AB-F1236D |

|

|

Human CD56 |

5.1H11 |

PE |

E-AB-F1239D |

|

|

Mouse CD45 |

30-F11 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1136S |

|

|

Mouse CD3 |

17A2 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1013C |

Detection of Mouse NK Cells |

|

Mouse CD19 |

1D3 |

PE/Cyanine7 |

E-AB-F0986H |

|

|

Mouse NK1.1 |

PK136 |

APC |

E-AB-F0987E |

|

|

Anti-Human CD3-FITC/CD19-APC/CD16+CD56-PE Cocktail |

E-AB-FC0009 |

|||

|

Anti-Human CD19-FITC/CD56-PE/CD3-PE/Cyanine7/CD45-PerCP Cocktail |

E-AB-FC0011 |

FCM antibody cocktail |

||

|

Anti-Human CD3-FITC/CD19-APC/CD16+CD56-PE Cocktail |

E-AB-FC0007 |

|||

Table. 6 Reagents for NK Cells Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

Human PBMC Separation Solution(P 1.077) |

E-CK-A103 |

|

EasySortTM Human Naïve Pan T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH006N |

|

EasySort™ Human Naïve CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH007N |

|

EasySort™ Human Naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH008N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Pan-Naïve T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM006N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Naïve CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM007N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM008N |

|

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

E-CK-A091 |

|

Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIH001A |

|

CFSE Cell Division Tracker Kit |

E-CK-A345 |

|

EasySort™ Human CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH001N |

|

Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit |

E-CK-A108 |

|

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

E-CK-A109 |

|

EasySort™-5 Magnet |

EC001 |

|

10×ACK Lysis Buffer |

E-CK-A105 |

References:

[1] Huntington N D , Cursons J , Rautela J .The cancer–natural killer cell immunity cycle[J].Nature Reviews Cancer[2025-11-04].DOI:10.1038/s41568-020-0272-z.

[2] Shimasaki, N., Jain, A., & Campana, D. (2020). NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 19(3), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1.

[3] Wu S Y , Fu T , Jiang Y Z ,et al.Natural killer cells in cancer biology and therapy[J].Molecular Cancer, 2020, 19(1).DOI:10.1186/s12943-020-01238-x.

[4] Vivier, E., Tomasello, E., Baratin, M., Walzer, T., & Ugolini, S. (2008). Functions of natural killer cells. Nature Immunology, 9(5), 503–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1582.

[5] Caligiuri, M. A. (2008). Human natural killer cells. Blood, 112(3), 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438.

[6] Geiger, T. L., & Sun, J. C. (2016). Development and maturation of natural killer cells. Current Opinion in Immunology, 39, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2016.01.007.

[7] Cherrier DE, Serafini N, Di Santo JP. Innate Lymphoid Cell Development: A T Cell Perspective. Immunity. 2018;48:1091–103.

[8] Zhang Y, Wallace DL, de Lara CM, Ghattas H, Asquith B, Worth A, Griffin GE, Taylor GP, Tough DF, Beverley PC, Macallan DC. In vivo kinetics of human natural killer cells: the effects of ageing and acute and chronic viral infection. Immunology. 2007;121:258–65.

[9] Chiossone L, Dumas PY, Vienne M, Vivier E. Natural killer cells and other innate lymphoid cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:671–88.

[10] Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1025–36.

[11] Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Spies T. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–9.

[12] Amin PJ, Shankar BS. Sulforaphane induces ROS mediated induction of NKG2D ligands in human cancer cell lines and enhances susceptibility to NK cell mediated lysis. Life Sci. 2015;126:19–27.

[13] Sungur CM, Tang-Feldman YJ, Ames E, Alvarez M, Chen M, Longo DL, Pomeroy C, Murphy WJ. Murine natural killer cell licensing and regulation by T regulatory cells in viral responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110: 7401–6.

[14] Sliz A, Locker KCS, Lampe K, Godarova A, Plas DR, Janssen EM, Jones H, Herr AB, Hoebe K. Gab3 is required for IL-2- and IL-15-induced NK cell expansion and limits trophoblast invasion during pregnancy. Sci Immunol. 2019;4(38): eaav3866. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aav3866.

[15] Delconte RB, Kolesnik TB, Dagley LF, Rautela J, Shi W, Putz EM, Stannard K, Zhang JG, Teh C, Firth M, et al. CIS is a potent checkpoint in NK cells mediated tumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:816–24.

[16] Vivier, E., Tomasello, E., Baratin, M., Walzer, T., & Ugolini, S. (2008). Functions of natural killer cells. Nature Immunology, 9(5), 503–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1582.

[17] Sharrock, J. (2019). Natural Killer Cells and Their Role in Immunity. EMJ Allergy & Immunology, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.33590/emjallergyimmunol/10311326.

[18] Bitsue, Dr. Z. K. (2021). The role of Natural killer (NK) cells as APCs, Cytotoxicity, Immuno-regulatory in Innate and Adaptive immune as Potential Therapeutic and Preventive Target in Infectious Diseases. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 12(04), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.14299/ijser.2021.04.09.

[19] Sun, J. C., Beilke, J. N., & Lanier, L. L. (2009). Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature, 457(7229), 557–561. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07665.

[20] Mujal, A. M., Delconte, R. B., & Sun, J. C. (2021). Natural Killer Cells: From Innate to Adaptive Features. Annual Review of Immunology, 39(1), 417–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-074948.

[21] Grégoire, C., Chasson, L., Luci, C., Tomasello, E., Geissmann, F., Vivier, E., & Walzer, T. (2007). The trafficking of natural killer cells. Immunological Reviews, 220(1), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065x.2007.00563.x.

[22] Collins, P. L., Cella, M., Porter, S. I., Li, S., Gurewitz, G. L., Hong, H. S., Johnson, R. P., Oltz, E. M., & Colonna, M. (2019). Gene Regulatory Programs Conferring Phenotypic Identities to Human NK Cells. Cell, 176(1–2), 348-360.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.045.

[23] Pierce, S., Geanes, E. S., & Bradley, T. (2020). Targeting Natural Killer Cells for Improved Immunity and Control of the Adaptive Immune Response. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00231.

[24] Murphy, J. (2022). Natural Killer Cells: Future Role for Cancer Immunotherapy. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Bio-Medical Science, 02(06). https://doi.org/10.47191/ijpbms/v2-i6-01.

[25] Hu, W., Wang, G., Huang, D., Sui, M., & Xu, Y. (2019). Cancer Immunotherapy Based on Natural Killer Cells: Current Progress and New Opportunities. Frontiers in Immunology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01205.

[26] Tang, J., Zhu, Q., Li, Z., Yang, J., & Lai, Y. (2022). Natural Killer Cell-targeted Immunotherapy for Cancer. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 17(6), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574888x17666220107101722.

[27] Shang, J., Hu, S., & Wang, X. (2024). Targeting natural killer cells: from basic biology to clinical application in hematologic malignancies. Experimental Hematology & Oncology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-024-00481-y.

[28] Bexte, T., Reindl, L. M., & Ullrich, E. (2023). Nonviral technologies can pave the way for CAR-NK cell therapy. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 114(5), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleuko/qiad074.

[29] Pan, W., Tao, T., Qiu, Y., Zhu, X., & Zhou, X. (2024). Natural killer cells at the forefront of cancer immunotherapy with immune potency, genetic engineering, and nanotechnology. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 193, 104231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104231.