The skin is the body’s primary interface with the external environment and sustains a complex immune landscape dominated by cutaneous T cells. This population comprises an estimated 20 billion cells, nearly double the count in systemic circulation, and is indispensable for mediating immune surveillance, preserving tissue homeostasis, and orchestrating adaptive responses to pathogenic insults and tissue injury. A critical subset, tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells, persists permanently in the skin to provide rapid and long-lasting immunity, interacting with commensal microbiota and contributing to both pathologic and protective responses, such as in tumor suppression[1]. The orchestration of T cell immunity relies on dynamic crosstalk with structural cells like keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which sense environmental insults and relay barrier status. When dysregulated, these intricate interactions underpin the development of inflammatory skin diseases and malignancies, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)[1,2].

This paper focuses on cutaneous T cells, covering their definition, differences from peripheral T cells, roles in skin immunity, and related immunological mechanisms. It also discusses cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) as well as the immunophenotypic and molecular characteristics of this malignancy.

Table of Contents

1. What are cutaneous T cells?

2. Cutaneous T cell vs peripheral T cell

3. Cutaneous T cell immunology

4. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

5. Immunophenotypes and Molecular Characteristics in CTCL

01 What are cutaneous T cells?

Cutaneous T cells consist of resident and migratory subsets, among which tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM cells) are pivotal for long-term immunity. By persisting permanently in the skin and excluding systemic circulation, TRM cells confer rapid protection against recurrent infections and environmental challenges. They underpin effective cutaneous immunity through collaboration with commensal bacteria to sustain immune surveillance and tissue homeostasis, while also participating in the pathogenesis of diverse skin disorders and exerting tumor-suppressive effects[1,2].

The crosstalk between cutaneous T cells and other skin-resident components (e.g., keratinocytes, fibroblasts) is equally critical. As the outermost barrier-forming cells, keratinocytes function as sentinels to sense perturbations in barrier integrity, microbial ligands, and stress signals. They perpetually relay tissue status to the cutaneous immune system, orchestrating T-cell-mediated immune responses to tissue damage. Cutaneous T cells in turn induce distinct cellular responses in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts, with these interactions linked to the development of inflammatory skin diseases[3,4].

Beyond their protective functionalities, dysregulation of cutaneous T cells contributes to a spectrum of dermatological conditions, encompassing inflammatory disorders and malignancies such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

02 Cutaneous T cell vs peripheral T cell

Cutaneous T cells and peripheral T cells exhibit fundamental differences in localization, phenotypic characteristics, functional specialization, and molecular regulatory networks, reflecting their distinct adaptive roles in tissue-specific immunity versus systemic immune responses.

Cutaneous T cells are predominantly tissue-resident (e.g., TRM cells) or tissue-associated, persisting in the cutaneous microenvironment without recirculating systemically. They express tissue-homing markers (e.g., CD69, CD103) and prioritize rapid local responses to pathogens, tissue damage, or commensal perturbations, while maintaining skin homeostasis[5,7]. In contrast, peripheral T cells primarily circulate through blood and lymphoid organs (e.g., lymph nodes, spleen), expressing systemic homing receptors (e.g., CXCR4, CCR7) and mediating broad systemic immune surveillance, pathogen clearance, and immune regulation across multiple tissues[6,7].

Functionally, cutaneous T cells are specialized in site-specific immune memory and barrier defense, with enhanced cytotoxicity and cytokine production tailored to skin microenvironmental cues. Peripheral T cells exhibit greater plasticity, participating in systemic immune responses, immune tolerance induction, and long-distance immune cell trafficking. Molecularly, the two populations differ in gene expression profiles (e.g., tissue residency-related genes in cutaneous T cells, circulation-associated genes in peripheral T cells), signaling pathway activation, and responses to inflammatory or regulatory cues, underpinning their tissue-adapted functional divergence[5,6,7].

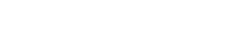

Fig. 1 Structure and cellular components of the skin and control of immunity by skin-resident microorganisms[16].

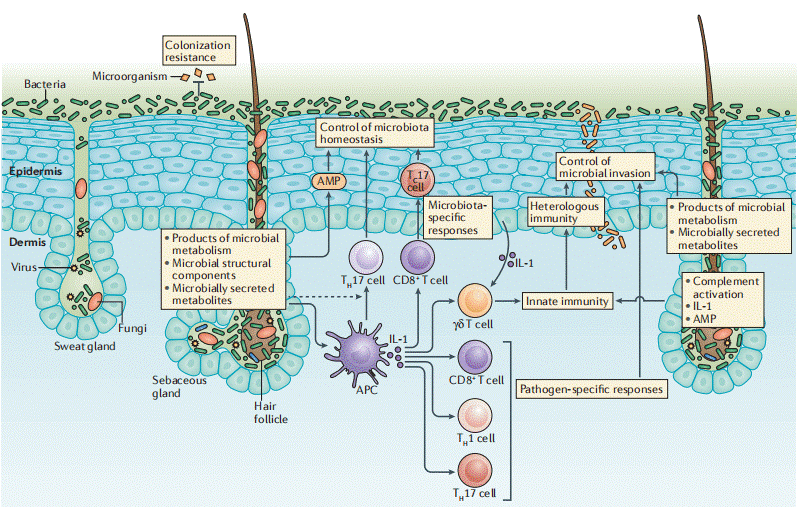

Fig. 2 Naive T/TCM/TEM cell detection of C57BL/6 mice in different tissues: Naive T cells exhibited the phenotype CD45+CD3+CD62L+CD44-, TCM cells exhibited the phenotype CD45+CD3+CD62L+CD44+, TEM cells exhibited the phenotype CD45+CD3+CD62L+CD44+/low.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table 1. Research Tools for Cutaneous Cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Applications |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1136J |

Detection of Mouse T cells |

|

CD3 |

17A2 |

APC |

E-AB-F1013E |

|

|

CD4 |

GK1.5 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 610 |

E-AB-F1097T |

|

|

CD8 |

53-6.7 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1104Q |

|

|

CD62L |

MEL-14 |

PE |

E-AB-F1011D |

|

|

CD44 |

IM7 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1100C |

Table 2. Reagents for Cutaneous Cells Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

CFSE Cell Division Tracker Kit |

E-CK-A345 |

|

DAPI Reagent (25 μg/mL) |

E-CK-A163 |

|

Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit |

E-CK-A108 |

|

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

E-CK-A109 |

|

EasySort™-5 Magnet |

EC001 |

|

Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIH001A |

|

Mouse CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIM001A |

|

APC Anti-Human CD69 Antibody[FN50] |

E-AB-F1138E |

|

PE Anti-Mouse CD25 Antibody[PC-61.5.3] |

E-AB-F1102D |

|

PE Anti-Human CD25 Antibody[BC96] |

E-AB-F1194D |

|

APC Anti-Mouse CD69 Antibody[H1.2F3] |

E-AB-F1187E |

03 Cutaneous T cell immunology

The skin plays a pivotal role in cutaneous immunity as an integral component of the skin immune system, mediating host defense and maintaining tissue homeostasis. Cutaneous T cell populations are highly specialized and heterogeneous, with functions spanning pathogen elimination, immune regulation, and repair of damaged tissues.

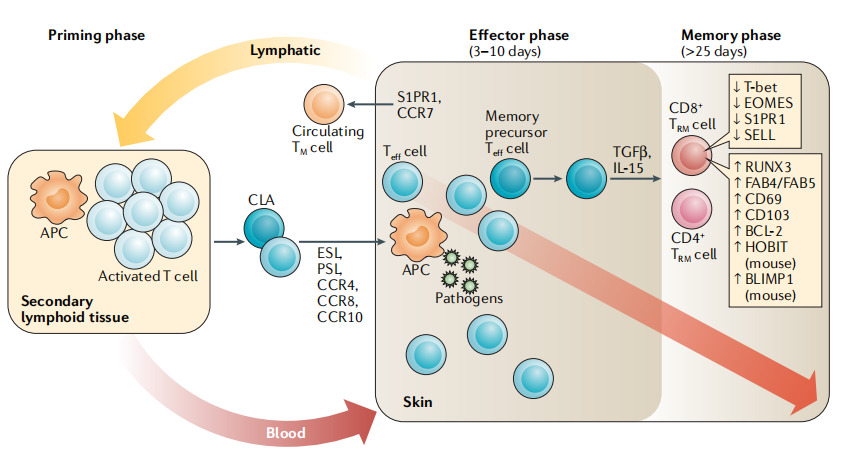

Rapid immune responses at the cutaneous barrier: Cutaneous T cells primarily comprise αβ T cells (the predominant subset) and γδ T cells. αβ T cells can be further subdivided into short-lived effector T cells (SLECs), central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), and tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM). Notably, TRM cells are critical for cutaneous immunity, they persist long-term in peripheral tissues and provide a rapid, local first line of defense against reencountered pathogens. TRM cells express lineage-defining markers such as CD69 and CD103, which are essential for their tissue retention, and their survival is regulated by cytokines including IL-7 and IL-15 secreted within the cutaneous microenvironment[6,7,8].

Immune surveillance and defense: Cutaneous T cells are key effectors of host resistance to pathogenic microbial invasion. They migrate to injured or infected skin sites, where they differentiate into antigen-specific effector T cells to orchestrate robust host immune responses. Memory T cells confer long-lasting immunity against subsequent immune challenges. While some T cells circulate continuously between the skin and bloodstream, others establish permanent residency in the skin and no longer reenter the systemic circulation. This tissue-resident memory T cell population rapidly responds to tissue stress signals via the lymphoid stress surveillance response (LSSR), thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of skin allergic disorders. T cell migration to the skin is dependent on the expression of specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors. Cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) is a critical skin-homing molecule that interacts with E-selectin on endothelial cells. Approximately 15% of circulating T cells express CLA; these CLA+ memory T cells are pivotal for local cutaneous immunity and are linked to inflammatory responses and tumor progression[2,5,9].

Regulation of inflammation and tissue repair: Cutaneous T cells cooperate with local epithelial and stromal cells to promote appropriate inflammatory responses and facilitate tissue repair post-injury. They modulate tissue remodeling by regulating cytokine and chemokine secretion from keratinocytes and fibroblasts. For example, cutaneous T cells enhance keratinocyte proliferation, migration, and differentiation, processes essential for wound healing and epidermal barrier restoration[3,4,6].

Suppressive functions of regulatory T cells (Tregs): The skin is enriched with CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), which play a central role in dampening inflammation and promoting tissue repair. By inhibiting effector T cell activity, Tregs prevent excessive immune responses from damaging host tissues, thereby sustaining cutaneous immune homeostasis[10].

Association with skin disease pathogenesis: Dysregulation of cutaneous T cell function is central to the pathogenesis of a broad spectrum of dermatological conditions. This encompasses inflammatory disorders such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, where dysregulated T cell activity underpins chronic inflammation; malignancies including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), whose major subtypes (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome) arise from skin-homing memory T cells; and HIV-associated immune dysregulation, which renders patients susceptible to severe non-infectious inflammatory skin reactions[9,11].

Cutaneous T cells are indispensable components of the skin immune system, exerting diverse and critical functions in immune surveillance, pathogen clearance, inflammatory regulation, and tissue repair. Their dysregulation contributes to a broad spectrum of skin disorders, ranging from inflammatory conditions to malignancies such as CTCL, underscoring their central importance in skin health and disease.

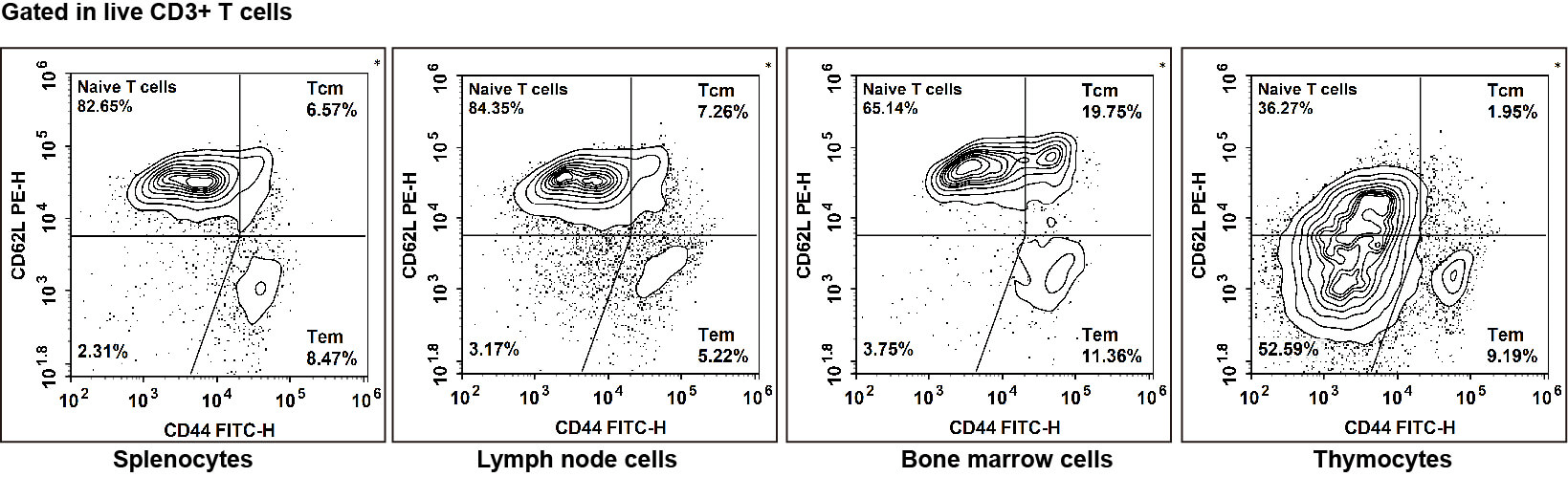

Fig. 3 The structure of the skin contributes to its immune functions[9].

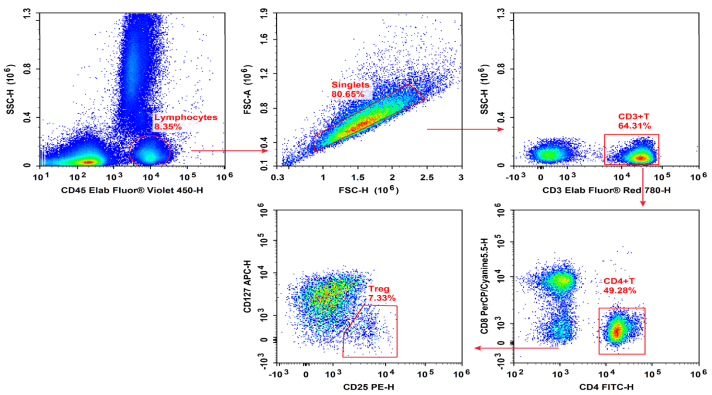

Fig. 4 Normal human peripheral blood cells are stained with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD45, Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Human CD3, FITC Anti-Human CD4, PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD8, PE Anti-Human CD25 and APC Anti-Human CD127, followed by analysis via flow cytometry. Treg cells exhibited the phenotype CD45+CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127low/-.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table 3. Research Tools for Treg Cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Applications |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Detection of Human Treg cells |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1230S |

|

|

CD4 |

SK3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1352C |

|

|

CD8 |

OKT-8 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1110J |

|

|

CD25 |

BC96 |

PE |

E-AB-F1194D |

|

|

CD127 |

A019D5 |

APC |

E-AB-F1152E |

04 Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) comprises a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas defined by the clonal expansion of malignant T cells with primary tropism for the skin. CTCL pathogenesis is multifactorial, typically originating from clonally expanded CD4+ T cells amid a milieu of chronic inflammation. These malignant T cells display pronounced skin tropism, infiltrating the cutaneous compartment and migrating into the epidermis. Although early-stage CTCL typically manifests as indolent cutaneous patches or plaques, approximately one-third of patients develop progressive disease, characterized by expanding skin lesions, overt tumors, and potential systemic dissemination of malignant T cells[12,13].

CTCL encompasses multiple subtypes, with mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sezary syndrome as the most prevalent, collectively accounting for the majority of cases[15]. MF is classically an indolent subtype presenting with patches, plaques, and tumors, whereas Sezary syndrome represents a more aggressive, leukemic variant. Additional subtypes include primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma[14,15].

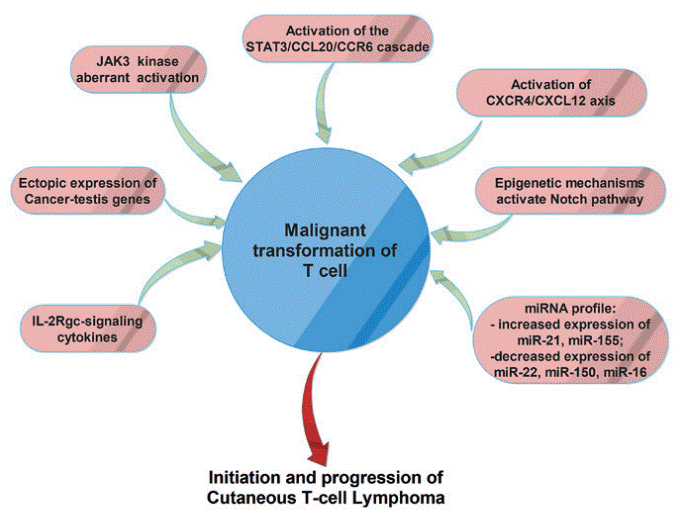

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often arises amid immunosuppression and immune evasion, with malignant T cells exhibiting an exhausted immune checkpoint profile that impairs antitumor immune responses[17]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) further contributes to CTCL progression through complex crosstalk between malignant T cells, inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, and the vascular network, while tumor cell- and stroma-derived factors accelerate angiogenesis in lesions to support tumor growth. Skin microbiota can modulate innate and adaptive immunity, and specific commensals may trigger or promote CTCL in individuals with genetic predispositions or altered immune states, as suggested by studies linking adaptive responses to skin commensals with clonal T-cell proliferation and transformation under appropriate genetic backgrounds[18]. Non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), have emerged as key regulators in CTCL pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy, as they orchestrate cellular processes including proliferation (e.g., MALAT1, miR-155), growth inhibition (e.g., miR-135a, miR-223), metastasis (e.g., miR-155, miR-1246), and programmed cell death (e.g., miR-155, miR-21), and interact with therapeutic agents such as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs), extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), and chemotherapy[18,19].

Diagnosing cutaneous lymphoma, particularly in early stages, poses a significant diagnostic challenge due to its clinical, histological, and immunophenotypic resemblance to benign inflammatory skin diseases[20]. Immunohistochemistry plays a crucial role in distinguishing malignant from benign T-cell infiltrates and in subtyping CTCL; for instance, loss of pan–T-cell markers such as CD7 is frequently observed in mycosis fungoides (MF), whereas CD30 expression characterizes certain lymphoproliferative disorders[21]. Treatment strategies are stage-dependent: early-stage indolent disease focuses on symptom control and quality of life, while advanced disease carries a poorer prognosis and requires targeted approaches. Monoclonal antibodies form a cornerstone of therapy for specific CTCL subtypes, including mogamulizumab (anti-CCR4) for certain T-cell malignancies and brentuximab vedotin (anti-CD30) for CD30-positive diseases. In contrast, rituximab (anti-CD20) is reserved for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas and is not used in CTCL[21]. A deeper understanding of cutaneous T-cell immunobiology is essential for deciphering disease mechanisms and developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for CTCL.

Fig. 5 The main molecular mechanisms involved in malignant transformation of T-cells in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas[18].

05 Immunophenotypes and Molecular Characteristics in CTCL

The immunophenotypic and molecular characteristics of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) subtypes are pivotal for diagnosis and elucidating disease progression, with distinct immunophenotypic profiles reflecting underlying genetic and signaling dysregulations. For Mycosis Fungoides (MF), the majority (69%) are CD4+ T cells, with smaller proportions being CD8+ (23%) or double-negative (CD4-/CD8-, 8%) [14,21]. MF cells typically express CD3, CD4, CD103, CCR4, IL-15R, IL-7R, and cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA), a molecule critical for skin homing[21]. Sezary syndrome cells also express CD3 and CD4, and additionally feature CD25, CCR7, IL-15R, and IL-7R expression, while CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders are defined by the expression of CD30, CD4, and CD56[19,21].

These subtype-specific immunophenotypes are closely linked to genetic aberrations, which play a crucial role in the pathogenesis and progression of CTCL and other T-cell lymphomas[22]. A spectrum of mutational signatures has been identified, with UV radiation recognized as a key driver of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma development. For example, genes such as TP53, CDKN2A/B, c-MYC, TET2, and DNMT3A are associated with MF, whereas TRAF2, BUB3, STAT3, and CARD11 are linked to Sezary syndrome[22], and these genetic mutations often perturb key signaling cascades. Specifically, signaling pathways including NF-κB, JAK-STAT, TCR signaling, and mTOR/PI3K/Akt are frequently dysregulated across different CTCL subtypes, thereby modulating the expression of signature surface antigens and regulating cell growth, survival, and proliferation[22,23].

Fig. 6 The generation and maintenance of cutaneous tissue-resident memory T cells[9].

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table 4. Research Tools for Cutaneous T Cells

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

Human CD30(Cluster of Differentiation 30) ELISA Kit |

E-EL-H6215 |

|

PE Anti-Human CD56/NCAM Antibody[5.1H11] |

E-AB-F1239D |

|

APC Anti-Human CD25 Antibody[BC96] |

E-AB-F1194E |

|

FITC Anti-Human CD197/CCR7 Antibody[G043H7] |

E-AB-F1159C |

|

FITC Anti-Mouse CD103 Antibody[M290] |

E-AB-F1090C |

|

Elab Fluor® 700 Anti-Human CD194/CCR4 Antibody[L291H4] |

E-AB-F1366M1 |

|

Uncoated Mouse IL-17RA ( Interleukin-17 receptor A ) ELISA Kit |

E-UNEL-M0179 |

|

Human PBMC Separation Solution(P 1.077) |

E-CK-A103 |

|

EasySort™ Human Naïve Pan T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH006N |

|

EasySort™ Human Naïve CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH007N |

|

EasySort™ Human Naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH008N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Pan-Naïve T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM006N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Naïve CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM007N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse Naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM008N |

|

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

E-CK-A091 |

|

Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIH001A |

|

CFSE Cell Division Tracker Kit |

E-CK-A345 |

|

EasySort™ Human CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH001N |

References:

[1] Zareie, P., Weiss, E. S., Kaplan, D. H., & Mackay, L. K. (2025). Cutaneous T cell immunity. Nature Immunology, 26(7), 1014–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02145-3.

[2] Ho, A. W., & Kupper, T. S. (2019). T cells and the skin: from protective immunity to inflammatory skin disorders. Nature Reviews Immunology, 19(8), 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0162-3.

[3] Morawski, P. A., DeBerg, H., Fahning, M. L., Gratz, I., & Campbell, D. J. (2021). Cutaneous T cells promote distinct cellular outcomes in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. The Journal of Immunology, 206(1_Supplement), 96.18-96.18. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.206.supp.96.18.

[4] Morawski, P. A., DeBerg, H., Pribitzer, S., Fahning, M., Stefani, C., Lacy-Hulbert, A., Gratz, I., & Campbell, D. J. (2023). Cutaneous T cells promote distinct outcomes in human skin structural cells associated with inflammatory disease. The Journal of Immunology, 210(Supplement_1), 170.16-170.16. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.210.supp.170.16.

[5] Seidel, J. A., Vukmanovic-Stejic, M., Muller-Durovic, B., Patel, N., Fuentes-Duculan, J., Henson, S. M., Krueger, J. G., Rustin, M. H. A., Nestle, F. O., Lacy, K. E., & Akbar, A. N. (2018). Skin resident memory CD8+ T cells are phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating populations and lack immediate cytotoxic function. Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 194(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.13189.

[6] Nanda, N. K. (2020). Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells: Sheltering-in-Place for Host Defense. Critical Reviews in Immunology, 40(5), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1615/critrevimmunol.2020035522.

[7] Khalil, S., Bardawil, T., Kurban, M., & Abbas, O. (2020). Tissue-resident memory T cells in the skin. Inflammation Research, 69(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-020-01320-6.

[8] Li, L., Liu, P., Chen, C., Yan, B., Chen, X., Li, J., & Peng, C. (2022). Advancements in the characterization of tissue resident memory T cells in skin disease. Clinical Immunology, 245, 109183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2022.109183.

[9] Ho, A. W., & Kupper, T. S. (2019). T cells and the skin: from protective immunity to inflammatory skin disorders. Nature Reviews Immunology, 19(8), 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0162-3.

[10] Ali, N., & Rosenblum, M. D. (2017). Regulatory T cells in skin. Immunology, 152(3), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12791.

[11] Nakai, S., Kiyohara, E., & Watanabe, R. (2021). Malignant and Benign T Cells Constituting Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(23), 12933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312933.

[12] Edelson, R. L. (1987). Cutaneous T cell Lymphoma. The Journal of Dermatology, 14(5), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.1987.tb03601.x.

[13] Querfeld, C., Leung, S., Myskowski, P. L., Curran, S. A., Goldman, D. A., Heller, G., Wu, X., Kil, S. H., Sharma, S., Finn, K. J., Horwitz, S., Moskowitz, A., Mehrara, B., Rosen, S. T., Halpern, A. C., & Young, J. W. (2018). Primary T Cells from Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma Skin Explants Display an Exhausted Immune Checkpoint Profile. Cancer Immunology Research, 6(8), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-17-0270.

[14] Willemze, R. (2014). CD30-Negative Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Other than Mycosis Fungoides. Surgical Pathology Clinics, 7(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2014.02.006.

[15] Winsett, F., Ni, X., & Duvic, M. (2016). Mogamulizumab in the treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs, 4(12), 1277–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678707.2016.1253469.

[16] Belkaid Y , Tamoutounour S .The influence of skin microorganisms on cutaneous immunity[J].Nature Reviews Immunology, 2016, 16(6):353.DOI:10.1038/nri.2016.48.

[17] Querfeld, C., Leung, S., Myskowski, P. L., Curran, S. A., Goldman, D. A., Heller, G., Wu, X., Kil, S. H., Sharma, S., Finn, K. J., Horwitz, S., Moskowitz, A., Mehrara, B., Rosen, S. T., Halpern, A. C., & Young, J. W. (2018). Primary T Cells from Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma Skin Explants Display an Exhausted Immune Checkpoint Profile. Cancer Immunology Research, 6(8), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-17-0270.

[18] Tanase, C., Popescu, I., Enciu, A., Gheorghisan‑Galateanu, A., Codrici, E., Mihai, S., Albulescu, L., Necula, L., & Albulescu, R. (2018). Angiogenesis in cutaneous T‑cell lymphoma ‑ proteomic approaches (Review). Oncology Letters. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.9734.

[19] He, X., Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., Sun, J., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, C. (2024). Non-coding RNAs in the spotlight of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Cell Death Discovery, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02165-2.

[20] Hague, C., Farquharson, N., Menasce, L., Parry, E., & Cowan, R. (2022). Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: diagnosing subtypes and the challenges. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 83(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2021.0149.

[21] Wechsler, J., Ingen-Housz-Oro, S., Deschamps, L., Brunet-Possenti, F., Deschamps, J., Delfau, M.-H., Calderaro, J., & Ortonne, N. (2022). Prevalence of T-cell antigen losses in mycosis fungoides and CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferations in a series of 153 patients. Pathology, 54(6), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2022.02.008.

[22] Kumar, S., Dhamija, B., Attrish, D., Sawant, V., Sengar, M., Thorat, J., Shet, T., Jain, H., & Purwar, R. (2022). Genetic alterations and oxidative stress in T cell lymphomas. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 236, 108109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108109.

[23] Jones, C. L., Degasperi, A., Grandi, V., Amarante, T. D., Ambrose, J. C., Arumugam, P., Baple, E. L., Bleda, M., Boardman-Pretty, F., Boissiere, J. M., Boustred, C. R., Brittain, H., Caulfield, M. J., Chan, G. C., Craig, C. E. H., Daugherty, L. C., de Burca, A., Devereau, A., … Whittaker, S. J. (2021). Spectrum of mutational signatures in T-cell lymphoma reveals a key role for UV radiation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83352-4.