B lymphocytes (B cells) are a core component of the adaptive immune system, and their multifaceted roles in breast cancer initiation, progression, and therapeutic response have attracted increasing attention in oncology and immunology research. Unlike the well-characterized functions of cytotoxic T cells in anti-tumor immunity, B cells exert dual regulatory effects on breast cancer progression, exerting both anti-tumor and pro-tumor activities that are dependent on their subset identity, differentiation status, tumor microenvironment (TME) cues, and crosstalk with other immune and stromal components.

This review synthesizes current understanding of the role of B cells in breast cancer immunotherapy. It examines the distinct yet complementary roles of innate and adaptive immunity in breast cancer, with a specific focus on the function of B cells and the antibodies they produce in mediating antitumor responses. Furthermore, it discusses the potential of integrating B cell profiles into personalized medicine strategies for breast cancer, while also addressing the key challenges associated with harnessing B cells as a therapeutic tool.

Table of Contents

1. The role of B cells in breast cancer immunotherapy

2. Subset-specific roles of B Cells in breast cancer

3. Role of antibodies produced by B cells against breast cancer

4. Importance of B cells in personalized medicine approaches for breast cancer

5. Challenges faced when using B cells as a tool against breast cancer

01 The role of B cells in breast cancer immunotherapy

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide, and the advent of immunotherapy has revolutionized its treatment paradigm. While cytotoxic T cells have long been the focus of anti-tumor immunity research, accumulating evidence highlights the multifaceted and critical role of B cells in the immunotherapy. B cells, as core components of the adaptive immune system, display dual functionality by either promoting or suppressing anti-tumor immunity, with the outcome determined by their subset differentiation, spatial distribution within the tumor microenvironment (TME), and crosstalk with other immune cells. In their anti-tumor capacity, B cells contribute to immunosurveillance through several mechanisms[1].

Antibody Production (B Cells Antibody Mediated Immunity): B cells produce antibodies that can directly target and eliminate tumor cells through mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement activation[2].

Antigen Presentation: B cells can recognize tumor-associated antigens, process them, and present them to T cells, thereby initiating or enhancing anti-tumor T cell responses. This T cell-B cell crosstalk is crucial for robust adaptive immunity[3].

Cytokine secretion: B cells can secrete various cytokines that influence the immune response within the TME[3].

Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLSs): Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLSs), ectopic lymphoid aggregates in the tumor microenvironment (TME), are closely associated with favorable prognosis in breast cancer patients due to the presence of B cells and plasma cells within them. These structures facilitate local adaptive anti-tumor cellular and humoral immune responses. TLS formation involves intricate crosstalk among B cells, T cells, and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). Within these structures, naive B cells can interact with helper T cells, which provide co-stimulatory signals and cytokines like IL-6 and IL-21, essential for B cell activation, proliferation, class-switch recombination, and somatic hypermutation. This process leads to the differentiation of activated B cells into plasma cells, which secrete antibodies, and memory B cells for long-term immunity[4].

Conversely, B cells can exert prominent pro-tumorigenic functions via their immunosuppressive capacity through a repertoire of distinct mechanisms. First, B cells secrete immunosuppressive cytokines such as interleukin‑10 (IL‑10), which dampen anti‑tumor immune responses. This function is notably executed by regulatory B cells (Bregs). For example, BAFF‑induced IL‑10‑secreting Bregs in triple‑negative breast cancer (TNBC) and CD301b lectin‑expressing Breg subsets have been shown in murine models to directly suppress T cell‑mediated anti‑tumor immunity. Second, B cells produce tumor‑promoting antibodies that facilitate immune evasion and tumor progression, contrasting with anti‑tumor antibody subsets. Finally, B cells contribute to remodeling the tumor microenvironment (TME) through pathways involving extracellular vesicles and the Liver X receptor (LXR)‑dependent transcriptional network, thereby establishing a permissive niche that supports tumor survival and metastatic dissemination[5].

The diverse functional roles of B cells are further illustrated by their ability to either activate or inhibit immune responses within the TME, with significant implications for patient outcomes.

02 Subset-specific roles of B cells in breast cancer

Different B cell subsets exert distinct effects within the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Tumor-infiltrating B cells (TiBs): These cells infiltrate the breast cancer TME and can be categorized into subsets, including naive B cells, memory B cells, and plasma cells, according to their activation status. Numerous clinical studies have demonstrated that a high density of TiBs, particularly memory B cells and plasma cells, is associated with improved survival in breast cancer patients. These cells locally secrete tumor-specific antibodies, present antigens to T cells, and recruit other immune cells to form tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs): organized lymphoid aggregates within the TME that are strongly associated with favorable therapeutic responses and prognosis[6].

Regulatory B cells (Bregs): Bregs are a immunosuppressive subset that inhibits anti-tumor immunity by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) and expressing inhibitory molecules (e.g., PD-L1). In breast cancer, Bregs accumulate in the TME and peripheral circulation, suppressing the proliferation and function of CD8⁺ cytotoxic T cells and promoting the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs). This leads to immune evasion of breast cancer cells and resistance to immunotherapy. The proportion of Bregs is positively correlated with tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients[7].

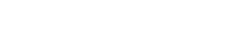

Fig. 1 Flow cytometry staining of human B cells. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes are stained with APC Anti-Human CD19 Antibody (E-AB-F1004E) and Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD20 Antibody (E-AB-F1045Q) (Left). Lymphocytes are stained with APC Anti-Human CD19 Antibody and Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Mouse IgG2b, κ Isotype Control (Right). (The datas are provided by Elabceience.)

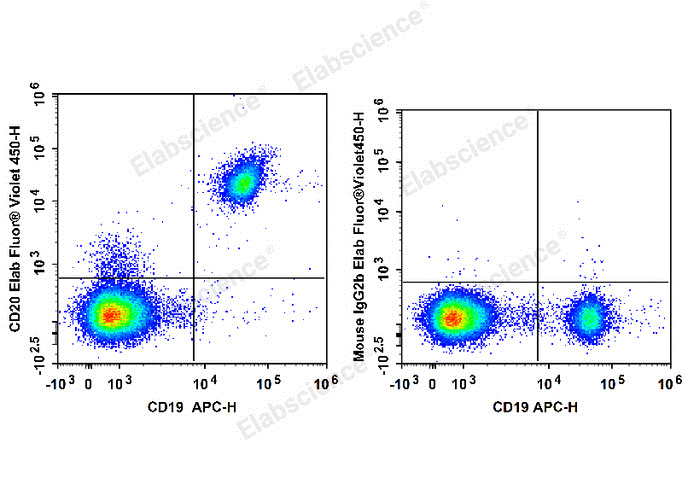

Fig. 2 Flow cytometry staining of mouse B cells. Staining of C57BL/6 murine splenocytes with APC Anti-Mouse CD3 Antibody[17A2] and Elab Fluor® Violet 540 Anti-Mouse CD45R/B220 Antibody[RA3.3A 1/6.1](left) or Elab Fluor® Violet 540 Rat IgM, κ Isotype Control(right). Total viable cells were used for analysis. (The datas are provided by Elabceience.)

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table.1 Multicolor Panel for Flow Cytometric Analysis of B Cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Species Reactivity |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1136J |

Mouse |

|

CD3 |

17A2 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1013C |

Mouse |

|

CD4 |

GK1.5 |

PE |

E-AB-F1097D |

Mouse |

|

CD8a |

53-6.7 |

APC |

E-AB-F1104E |

Mouse |

|

CD19 |

1D3 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F0986S |

Mouse |

|

CD20 |

SA271G2 |

PE/Cyanine5 |

E-AB-F1403G |

Mouse |

|

CD45R/B220 |

RA3.3A 1/6.1 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 540 |

E-AB-F1112T3 |

Mouse |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Human |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1230S |

Human |

|

CD4 |

SK3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1352C |

Human |

|

CD8 |

OKT-8 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1110J |

Human |

|

CD10 |

HI10a |

Elab Fluor® 647 |

E-AB-F1141M |

Human |

|

CD27 |

O323 |

PE/Cyanine7 |

E-AB-F1140H |

Human |

|

CD38 |

HIT2 |

Elab Fluor® 700 |

E-AB-F1058M1 |

Human |

|

CD19 |

CB19 |

PE |

E-AB-F1004D |

Human |

|

CD20 |

BCA/B20 |

APC |

E-AB-F1045E |

Human |

03 Role of antibodies produced by B cells against breast cancer

Antibodies produced by B cells play a critical and complex role in the immune response against breast cancer, contributing to both anti-tumor immunity and, in some contexts, potentially facilitating tumor progression. These roles are diverse, encompassing direct cytotoxic effects, antigen presentation, and the modulation of the tumor microenvironment (TME)[8].

One of the primary anti-tumor mechanisms of B cell-derived antibodies involves direct targeting and elimination of cancer cells. Antibodies can recognize tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) expressed on the surface of breast cancer cells. Once bound, these antibodies can trigger several effector functions, including antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). In ADCC, the antibody-coated tumor cells are recognized and killed by immune effector cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, which bind to the Fc region of the antibodies. In CDC, the binding of antibodies activates the complement cascade, leading to the formation of the membrane attack complex and subsequent lysis of the tumor cells. This direct cytotoxic potential makes B cell-derived antibodies a valuable component of the anti-cancer immune response[9].

Beyond direct cytotoxicity, antibodies contribute to anti-tumor immunity by facilitating antigen presentation. B cells, through their B cell receptors, can efficiently internalize TAAs, process them, and present them to T cells via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules[10]. This antigen presentation is crucial for activating and expanding anti-tumor T cell responses, especially follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, which in turn support B cell differentiation and antibody production within tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs). TLSs are ectopic lymphoid aggregates found within the TME that resemble secondary lymphoid organs and are sites where robust adaptive anti-tumor cellular and humoral immune responses can be elaborated. The presence of B cells and plasma cells within these TLSs is frequently associated with improved clinical outcomes and enhanced responses to immunotherapy in various cancers, including breast cancer. The antibodies produced within these structures are often highly specific and of high affinity, further enhancing their therapeutic potential[10].

For instance, in breast cancer, the immune microenvironment is highly influenced by the interplay between various immune cells and cancer cells. Different subtypes of breast cancer, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+), and luminal subtypes, exhibit distinct immune landscapes[11]. In TNBC, which is characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 expression, the presence of tumor infiltrating B cells and their secreted antibodies has been linked to better overall survival and response to treatment. This suggests that in certain breast cancer contexts, the humoral immune response mediated by B cells and their antibodies is a significant factor in prognosis[11].

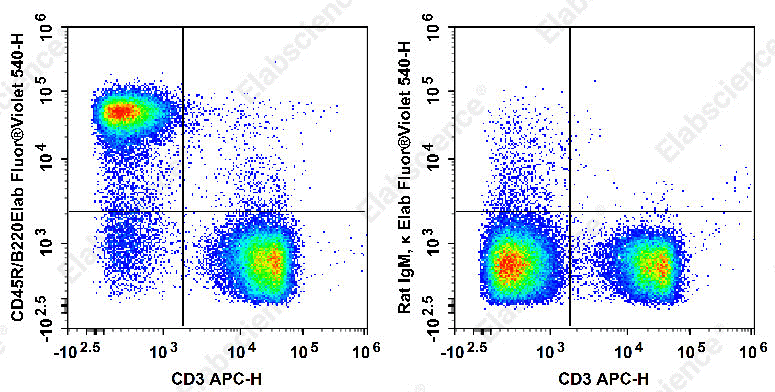

Fig. 3 Flow cytometry staining of human TBNK cells. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes are stained with Anti-Human CD19-FITC/CD56-PE/CD3-PE/Cyanine7/CD45-PerCP Cocktail (E-AB-FC0011). (The datas are provided by Elabceience.)

04 Importance of B cells in personalized medicine approaches for breast cancer

Once largely overlooked in cancer immunology, B cells are now recognized as pivotal players in breast cancer with multifaceted roles. They can promote anti-tumor immunity through antibody production, antigen presentation, and enhancing T-cell responses within tertiary lymphoid structures, while also contributing to tumor progression via immunosuppressive B-cell subsets. This dual functionality, together with their dynamic engagement across distinct breast cancer molecular subtypes, positions B cells as pivotal players in personalized medicine, endowing them with dual roles as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Their modulation, whether in combination with chemotherapy or through emerging B-cell-specific immune checkpoints, offers promising avenues for tailored therapeutic strategies[12].

In personalized medicine, the goal is to harness the beneficial aspects of B cell immunity while counteracting their pro-tumorigenic effects. This involves:

Biomarker Identification: Utilizing advanced techniques like single-cell sequencing to identify specific B cell subpopulations and their gene expression profiles that correlate with patient prognosis and response to therapy[13].

Targeted Therapies: Developing drugs that selectively modulate B cell activity, for example, by blocking immunosuppressive B cell subsets or enhancing the function of anti-tumorigenic B cells[13].

Immunotherapy Combinations: Designing combination therapies that integrate B cell-targeting agents with existing immunotherapies or chemotherapy to achieve synergistic anti-tumor effects[14].

Overall, the evolving understanding of B cells’ diverse roles underscores their significance as promising targets for anti-tumor therapies in breast cancer and their increasing relevance in developing precision and personalized treatment strategies.

05 Challenges faced when using B cells as a tool against breast cancer

Despite the growing recognition of B cells as a promising target for breast cancer immunotherapy and personalized medicine, translating B cell-based strategies from preclinical research to clinical practice is hindered by multiple interconnected challenges. These hurdles span from the intrinsic complexity of B cell biology to technical limitations in detection and clinical trial design. This section systematically summarizes the core challenges and bottlenecks in the development and application of B cell-targeted breast cancer therapies.

5.1 Intrinsic Functional Heterogeneity of B Cells and Difficulty in Precise Subtyping

The dual pro-tumor and anti-tumor roles of B cells in the breast cancer tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) are the primary barrier to their clinical application. This heterogeneity is manifested at multiple levels:

Subset heterogeneity: Tumor-infiltrating B cells (TIL-Bs) consist of multiple functionally distinct subsets, including effector B cells, memory B cells, plasma cells, and regulatory B cells (Bregs). Current phenotypic markers (e.g., CD20, CD38, IL-10) cannot fully distinguish between these subsets with high specificity. For example, IL-10 is not a unique marker of Bregs, as some effector B cells can transiently secrete IL-10 under inflammatory conditions, leading to misclassification of functional subsets[15].

Spatial heterogeneity: The function of B cells is closely related to their localization in the TIME. B cells in tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) exhibit strong anti-tumor activity by participating in antigen presentation and T cell activation, while scattered B cells in the tumor parenchyma may differentiate into Bregs under the influence of inhibitory factors. However, current detection techniques (e.g., immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry) lack the ability to accurately map the spatial distribution of B cell subsets at single-cell resolution, making it impossible to correlate localization with function[15].

Dynamic heterogeneity: B cell subsets undergo dynamic transformation during tumor progression and treatment. For example, chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can induce the conversion of Bregs to effector B cells, or vice versa, depending on the treatment regimen and patient immune status. This dynamic change makes it difficult to determine the optimal timing for B cell-targeted intervention[16].

5.2 Limitations of Detection Technology and Lack of Standardized Biomarkers

The clinical application of B cell-based strategies relies on accurate detection and quantification of functional B cell subsets and related biomarkers, but this is constrained by technical and standardization issues:

Technical limitations of detection methods: Conventional methods such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) can only detect a limited number of B cell markers, failing to capture the full spectrum of B cell functional heterogeneity. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics can provide high-resolution B cell profiling, but these techniques are costly, time-consuming, and require specialized bioinformatics analysis, making them unsuitable for routine clinical testing. B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing, a key tool for identifying tumor-specific B cells, faces challenges such as low sequencing depth and difficulty in distinguishing tumor-specific clones from bystander clones[17].

Lack of standardized biomarkers: Most B cell-related biomarkers (e.g., TIL-B density, Breg frequency, BCR clonal expansion) are still in the exploratory stage, with no unified detection standards or cutoff values. For example, different studies use different antibodies and counting methods to quantify CD20+ TIL-Bs, leading to inconsistent results across studies. Additionally, the predictive value of a single biomarker is limited; combined detection of multiple biomarkers (e.g., TIL-B subsets + TLS density + BCR repertoire) is required, but the optimal combination has not been defined[18].

5.3 Off-Target Effects of B Cell-Targeted Therapies and Difficulty in Efficacy Balance

Current B cell-targeted strategies often fail to specifically distinguish between beneficial effector B cells and harmful Bregs, resulting in off-target effects that compromise therapeutic efficacy:

Non-specific depletion of B cell subsets (B Cell Depletion): Therapeutic agents targeting pan-B cell markers (e.g., anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab) deplete both Bregs and effector B cells, thereby impairing humoral immunity and reducing the anti-tumor effect. Clinical studies have shown that rituximab combined with ICIs improves the efficacy of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) treatment in patients with high Breg infiltration, but reduces the treatment response in patients with high effector TIL-B infiltration[19].

Unpredictable immune modulation effects: Strategies to reprogram Bregs into effector B cells (e.g., TLR agonists, CD40 agonists) may have unpredictable effects on the immune system. For example, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides can activate both B cells and dendritic cells, potentially inducing excessive inflammatory responses or autoimmune reactions. In preclinical models, high-dose CpG treatment has been shown to cause systemic inflammation and damage to normal tissues[20].

Synergy challenges in combination therapy: B cell-targeted therapies are often used in combination with ICIs, chemotherapy, or targeted therapies, but the optimal combination regimen and sequence remain unclear. For example,when combined with chemotherapy, the timing of CD40 agonist administration affects B cell activation: administering CD40 agonists before chemotherapy may enhance the anti-tumor immune response, while administering them after chemotherapy may be ineffective due to the depletion of immune cells by chemotherapy[21].

5.4 Inhibition of B Cell Function by the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

The immunosuppressive breast cancer TIME creates a hostile environment for B cell activation and function, limiting the efficacy of B cell-targeted therapies:

Suppression by inhibitory cytokines and metabolites: The TIME is rich in inhibitory cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10, VEGF) secreted by tumor cells, Tregs, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). These cytokines inhibit B cell proliferation, differentiation into plasma cells, and antibody secretion, and promote the differentiation of naive B cells into Bregs. Additionally, tumor cell metabolism produces high levels of adenosine and lactic acid, which further impair B cell function by inhibiting the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., CD80, CD86) on B cells[22].

Lack of effective antigen presentation: Breast cancer cells often downregulate the expression of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or MHC-II molecules, reducing the ability of B cells to recognize and bind to tumor antigens. Even if B cells recognize TAAs, the absence of T cell help (due to T cell exhaustion in the TIME) prevents B cell activation and clonal expansion, resulting in weak humoral immune responses[22].

Impaired formation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS): TLS are key sites for B cell-T cell interaction and antibody production, but their formation is rare in most breast cancer subtypes, especially luminal-type breast cancer. Tumor stromal cells (e.g., fibroblasts) secrete factors that inhibit TLS formation, limiting the anti-tumor activity of B cells[23].

5.5 Limitations of Clinical Research and Difficulty in Patient Stratification

The translation of B cell-targeted therapies is also hindered by the limitations of clinical trial design and patient stratification:

Small sample size and heterogeneous patient populations: Most B cell-targeted therapy clinical trials are phase I/II studies with small sample sizes, and patients are often enrolled without considering breast cancer molecular subtypes or B cell immune profiles. This leads to inconsistent results across trials and makes it difficult to identify patient populations that benefit from treatment. For example, B cell-targeted therapies may be more effective in TNBC (which has high immunogenicity) than in luminal-type breast cancer, but this has not been confirmed in large-scale phase III trials[24].

Lack of predictive biomarkers for patient stratification: Currently, there are no validated biomarkers to select patients who are likely to benefit from B cell-targeted therapies. Patients with high effector TIL-B infiltration or tumor-specific BCR clones may respond better to B cell activation strategies, but without standardized detection methods, it is impossible to stratify patients accurately[25].

Difficulty in evaluating therapeutic efficacy: Traditional clinical efficacy endpoints (e.g., objective response rate, progression-free survival) do not fully reflect the immunomodulatory effects of B cell-targeted therapies. For example, B cell activation may lead to delayed tumor regression, and early tumor progression may be misinterpreted as treatment failure. Additionally, changes in B cell subsets and BCR repertoire after treatment are not included in routine efficacy evaluation, making it difficult to assess the mechanism of action of the therapy[26].

5.6 Risk of Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs)

B cell-targeted therapies may induce irAEs by disrupting the balance of the immune system, posing a risk to patient safety:

Humoral immune deficiency: Depletion of B cells or inhibition of B cell function may lead to hypogammaglobulinemia, increasing the risk of bacterial or viral infections. Clinical studies have reported that long-term use of anti-CD20 antibodies is associated with an increased incidence of pneumonia and herpes zoster in breast cancer patients[27].

Autoimmune reactions: Strategies to activate B cells (e.g., CD40 agonists, TLR agonists) may induce the production of autoantibodies, leading to autoimmune diseases such as thyroiditis, colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. In a phase II trial of CD40 agonist combined with PD-1 inhibitor for TNBC, 15% of patients developed grade 3 or higher autoimmune colitis, requiring treatment discontinuation[28].

In summary, the application of B cells as a therapeutic tool against breast cancer faces multiple challenges, including the functional heterogeneity of B cells, limitations of detection technology, off-target effects of therapies, immunosuppression by the TIME, clinical research limitations, and the risk of irAEs. Addressing these challenges requires interdisciplinary collaboration to develop high-resolution B cell detection technologies, identify specific biomarkers for functional subsets, design precise targeted strategies, and optimize clinical trial design based on patient immune profiles. Only by overcoming these hurdles can B cell-based therapies be fully integrated into personalized breast cancer treatment regimens.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table.2 Reagents for Breast Cancer Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

EasySort™ Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM004N |

|

EasySort™ Human B Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH004N |

|

Human Bcl-2 (B-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma 2) ELISA Kit |

E-EL-H0114 |

|

EasySort™ Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM004N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM001N |

|

EasySort™ Human CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH001N |

|

Human BAFF/CD257 (B-Cell Activating Factor) ELISA Kit |

E-EL-H0009 |

|

ATP Colorimetric Assay Kit (Enzyme Method) |

E-BC-K774-M |

|

ATP Chemiluminescence Assay Kit (Double Reagent) |

E-BC-F300 |

|

Mitochondrial Superoxide Fluorometric Assay Kit |

E-BC-F008 |

|

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Green) |

E-BC-K138-F |

|

FITC Anti-Human IL-10 Antibody[JES3-9D7] |

E-AB-F1198C |

|

Human IL-10(Interleukin 10)ELISA Kit |

E-EL-H6154 |

|

Human IFN-γ (Interferon Gamma) ELISPOT Kit |

ESP-H0002 |

|

Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) solid ELISPOT Kit |

ESP-H0009S |

References:

[1] Fridman WH, Meylan M, Petitprez F, Sun CM, Italiano A, Sautès-Fridman C. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of tumour immune contexture and clinical outcome. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022 Jul;19(7):441-457. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00619-z.

[2] García-Torralba E, Galluzzi L, Buqué A. Prognostic value of atypical B cells in breast cancer. Trends Cancer. 2024 Nov;10(11):990-991. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2024.09.009. Epub 2024 Oct 1.

[3] Xue D, Hu S, Zheng R, Luo H, Ren X. Tumor-infiltrating B cells: Their dual mechanistic roles in the tumor microenvironment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Oct;179:117436. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117436.

[4] Li K, Zhang C, Zhou R, Cheng M, Ling R, Xiong G, Ma J, Zhu Y, Chen S, Chen J, Chen D, Peng L. Single cell analysis unveils B cell-dominated immune subtypes in HNSCC for enhanced prognostic and therapeutic stratification. Int J Oral Sci. 2024 Apr 16;16(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41368-024-00292-1.

[5] Katakai T. Yin and yang roles of B lymphocytes in solid tumors: Balance between antitumor immunity and immune tolerance/immunosuppression in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Front Oncol. 2023 Jan 24;13:1088129. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1088129

[6] Toney NJ, Opdenaker LM, Frerichs L, Modarai SR, Ma A, Archinal H, Ajayi GO, Sims-Mourtada J. B cells enhance IL-1 beta driven invasiveness in triple-negative breast cancer. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 Dec 31:rs.3.rs-5153341. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-5153341/v1. Update in: Sci Rep. 2025 Jan 16;15(1):2211. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-86064-1.

[7] Pellegrino B, David K, Rabani S, Lampert B, Tran T, Doherty E, Piecychna M, Meza-Romero R, Leng L, Hershkovitz D, Vandenbark AA, Bucala R, Becker-Herman S, Shachar I. CD74 promotes the formation of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in triple-negative breast cancer in mice by inducing the expansion of tolerogenic dendritic cells and regulatory B cells. PLoS Biol. 2024 Nov 22;22(11):e3002905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002905.

[8] Garaud S, Zayakin P, Buisseret L, Rulle U, Silina K, de Wind A, Van den Eyden G, Larsimont D, Willard-Gallo K, Linē A. Antigen Specificity and Clinical Significance of IgG and IgA Autoantibodies Produced in situ by Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells in Breast Cancer. Front Immunol. 2018 Nov 20;9:2660. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02660.

[9] Cui W, Zhao Y, Shan C, Kong G, Hu N, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Ye L. HBXIP upregulates CD46, CD55 and CD59 through ERK1/2/NF-κB signaling to protect breast cancer cells from complement attack. FEBS Lett. 2012 Mar 23;586(6):766-71. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.039.

[10] Hermida-Prado F, Xie Y, Sherman S, Nagy Z, Russo D, Akhshi T, Chu Z, Feit A, Campisi M, Chen M, Nardone A, Guarducci C, Lim K, Font-Tello A, Lee I, García-Pedrero J, Cañadas I, Agudo J, Huang Y, Sella T, Jin Q, Tayob N, Mittendorf EA, Tolaney SM, Qiu X, Long H, Symmans WF, Lin JR, Santagata S, Bedrosian I, Yardley DA, Mayer IA, Richardson ET, Oliveira G, Wu CJ, Schuster EF, Dowsett M, Welm AL, Barbie D, Metzger O, Jeselsohn R. Endocrine Therapy Synergizes with SMAC Mimetics to Potentiate Antigen Presentation and Tumor Regression in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023 Oct 2;83(19):3284-3304. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-1711.

[11] Gonçalves IV, Pinheiro-Rosa N, Torres L, Oliveira MA, Rapozo Guimarães G, Leite CDS, Ortega JM, Lopes MTP, Faria AMC, Martins MLB, Felicori LF. Dynamic changes in B cell subpopulations in response to triple-negative breast cancer development. Sci Rep. 2024 May 21;14(1):11576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-60243-y.

[12] Lam BM, Verrill C. Clinical Significance of Tumour-Infiltrating B Lymphocytes (TIL-Bs) in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 11;15(4):1164. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041164.

[13] Holder AM, Dedeilia A, Sierra-Davidson K, Cohen S, Liu D, Parikh A, Boland GM. Defining clinically useful biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024 Jul;24(7):498-512. doi: 10.1038/s41568-024-00705-7.

[14] Desai D, Shende P. Strategic Aspects of NPY-Based Monoclonal Antibodies for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21(11):1097-1102. doi: 10.2174/1389203721666200918151604.

[15] Qin Y, Peng F, Ai L, Mu S, Li Y, Yang C, Hu Y. Tumor-infiltrating B cells as a favorable prognostic biomarker in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021 Jun 12;21(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02004-9.

[16] Wang L, Yang Y, Song Y, Zeng J, Zheng H, Wu X. Decoding tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes heterogeneity in ductal carcinoma in situ: immune microenvironment dynamics and prognostic insights. Discov Oncol. 2025 Jul 28;16(1):1435. doi: 10.1007/s12672-025-03288-3.

[17] Ding S, Chen X, Shen K. Single-cell RNA sequencing in breast cancer: Understanding tumor heterogeneity and paving roads to individualized therapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020 Aug;40(8):329-344. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12078.

[18] Arias-Pulido H, Cimino-Mathews A, Chaher N, Qualls C, Joste N, Colpaert C, Marotti JD, Foisey M, Prossnitz ER, Emens LA, Fiering S. The combined presence of CD20 + B cells and PD-L1 + tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in inflammatory breast cancer is prognostic of improved patient outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018 Sep;171(2):273-282. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4834-7.

[19] Li M, Quintana A, Alberts E, Hung MS, Boulat V, Ripoll MM, Grigoriadis A. B Cells in Breast Cancer Pathology. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 28;15(5):1517. doi: 10.3390/cancers15051517.

[20] Kang N, Duan Q, Min X, Li T, Li Y, Gao J, Liu W. Multifaceted function of B cells in tumorigenesis. Front Med. 2025 Apr;19(2):297-317. doi: 10.1007/s11684-025-1127-5.

[21] Chandnani N, Gupta I, Mandal A, Sarkar K. Participation of B cell in immunotherapy of cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2024 Mar;255:155169. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2024.155169.

[22] Yang S, Yang Y, Fang Y, Zhou Q, Sun W, Zhang Z, Yuan W, Li Z. Targeting tumour-infiltrating B cells: mechanisms and advances in cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2025 Nov 24;17(1):53. doi: 10.1038/s41419-025-08254-z.

[23] Esparcia-Pinedo L, Romero-Laorden N, Alfranca A. Tertiary lymphoid structures and B lymphocytes: a promising therapeutic strategy to fight cancer. Front Immunol. 2023 Aug 9;14:1231315. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1231315.

[24] Benvenuto M, Focaccetti C, Izzi V, Masuelli L, Modesti A, Bei R. Tumor antigens heterogeneity and immune response-targeting neoantigens in breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021 Jul;72:65-75. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.023.

[25] Parks RM, Alfarsi LH, Green AR, Cheung KL. Biology of primary breast cancer in older women beyond routine biomarkers. Breast Cancer. 2021 Sep;28(5):991-1001. doi: 10.1007/s12282-021-01266-5.

[26] Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Wang Z, Zhang T, Wu P, Huang J. Yin-yang effect of tumor infiltrating B cells in breast cancer: From mechanism to immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2017 May 1;393:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.008.

[27] Li M, Quintana A, Alberts E, Hung MS, Boulat V, Ripoll MM, Grigoriadis A. B Cells in Breast Cancer Pathology. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 28;15(5):1517. doi: 10.3390/cancers15051517.

[28] Bindu S, Bibi R, Pradeep R, Sarkar K. The evolving role of B cells in malignancies. Hum Immunol. 2025 May;86(3):111301. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2025.111301.