Neuroimmunology, a hybrid discipline integrating neuroscience and immunology, emphasizes bidirectional neuroimmune crosstalk between the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral immune system, which together form an integrated regulatory network modulating inflammatory responses and stress signaling. Anatomically, the CNS exhibits a brain-centric hierarchical architecture, whereas the immune system lacks a dominant anatomical hub and consists of dispersed lymphoid organs and tissue-resident leukocytes. Cellularly, neurons serve as the core functional units of the CNS (with glial cells providing supportive roles), while effector leukocytes,particularly brain-resident monocytes and T cells,mediate immune system function[1].

This article reviews T cell biology in neuroimmunology, T cell-nervous system interactions, the impact of T cell subtypes on neurological disorders, T cell contributions to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis(a representative form of brain degenerative diseases), Treg-mediated maintenance of neural homeostasis, and key advancements in T cell-targeted interventions for neurodegenerative diseases.

Table of Contents

1. T cell functions in neuroimmunology

2. How do T cells interact with the nervous system?

3. T cell subtypes and their impact on neurological disorders

4. The role of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in maintaining neural homeostasis

5. Role of T cells in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis

6. Research advancements in targeting T cells for neurodegenerative diseases

01 T cell functions in neuroimmunology

T cells are indispensable for maintaining physiological homeostasis, mediating diverse biological functions throughout the body with critical roles in immune surveillance, tissue protection, and reparative processes within the neuroimmunological axis. In the context of neural function, T cells exert beneficial effects on cognitive function[2], and deficits in T cell activity have been associated with cognitive impairment. The functional profile of T cells is highly context-dependent, varying with their anatomical localization: CNS-resident T cells mitigate secondary neuronal degeneration post-injury, enhance neuronal survival following CNS damage, and constrain inflammatory responses and associated tissue injury during pathological insults or infections. Following ischemic stroke, T cells suppress the proliferation of neurotoxic astrocytes to facilitate cerebral recovery. In the peripheral nervous system, T cells exert remote modulatory effects on cognition: subsequent to stress exposure, intestinal T cells secrete cytokines that signal to septal neurons, thereby attenuating anxiety and promoting cognitive resilience.

02 How do T cells interact with the nervous system?

The mode of crosstalk between the immune and nervous systems varies according to anatomical location, and can be categorized into two primary mechanisms: direct contact-dependent interactions and indirect signaling-mediated effects. Herein, we delineate the diverse modalities through which T cells interact with the nervous system across distinct bodily compartments.

brain

Numerous interactions between circulating or peripherally derived immune cells and the nervous system occur within the brain parenchyma. Despite its historical classification as an immune privileged site, the CNS undergoes active immune surveillance: leukocytes particularly monocytes and T cells can infiltrate the CNS via compromised blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity or chemotactic signaling (driven by C-C motif chemokine 1 (CCL1), CCL2, and CCL20), where they modulate neuronal function and cognition through the secretion of chemokines and cytokines. Following pathological insults such as stroke, sepsis, myocardial infarction, or social stress, T cells regulate synaptic plasticity, neuronal excitability, and microglial activation primarily via the release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and amphiregulin[1].

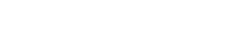

Spleen

The splenic nerve integrates CNS signals to modulate immune responses. Noradrenergic and cholinergic inputs from tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH+) neurons regulate plasma cell activity both by controlling T cell function and through direct interactions with B cells. Sensory neurons promote immune cell priming and polarization within germinal centers via the secretion of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)[1].

Lymph nodes and blood

TRPV+ sensory neurons and sympathetic nerve fibers regulate immune cell maturation, transcriptional programming, and lymphocyte activation. Neuroimmune signaling dynamically fine-tunes leukocyte trafficking, thereby modulating germinal center responses and T helper 1 (TH1) cell-mediated immune surveillance,effects mediated in part by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) transmits circadian rhythm signals to lymph nodes and blood vessels via norepinephrine, alongside inducing vascular contraction, which collectively drives leukocyte migration. Additionally, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis alters leukocyte distribution through systemic modulation of corticosterone levels[1].

Skin

Cutaneous sensory neurons shape immune responses through direct interactions with dendritic cells, macrophages, gamma delta T cells, and granulocytes. CGRP signaling modulates neutrophil recruitment,via dendritic cell-derived interleukin-23 (IL-23), regulates macrophage and lymphocyte function, and influences cytokine production by nearly all leukocyte subsets, in addition to shaping type 17 and type 2 immune responses[1].

Fig. 1 T cells in the spleen interact with the nervous system[1].

03 T cell subtypes and their impact on neurological disorders

In chronic inflammatory CNS disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS), T cells play a pivotal role in driving long-term pathophysiology: dysregulation of T cells within peripheral lymphoid organs orchestrates leukocyte infiltration into the CNS, culminating in immunopathology and neurological impairment. This pathological cascade is initiated by a CNS antigen-dependent mechanism, wherein conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) of peripheral lymphoid organs act as primary antigen-presenting cells,rather than neurovascular unit (NVU) macrophages or microglia,to mediate autoreactive T cell entry into the CNS and subsequent immunopathology[3].

In general, pathogenic CD4+ T cells within the brain interact with microglia via MHC class II molecules to drive local inflammatory responses. In contrast, neurons lack MHC class II expression and instead express MHC class I, enabling CD8+ T cells to exert cytotoxic activity and induce neuronal destruction. Beyond MHC class I-dependent mechanisms, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells can trigger neuronal death through cell–cell contact-dependent pathways involving Fas and Fas ligand[4].

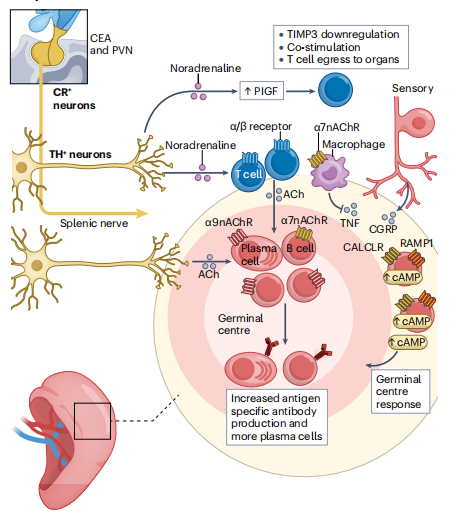

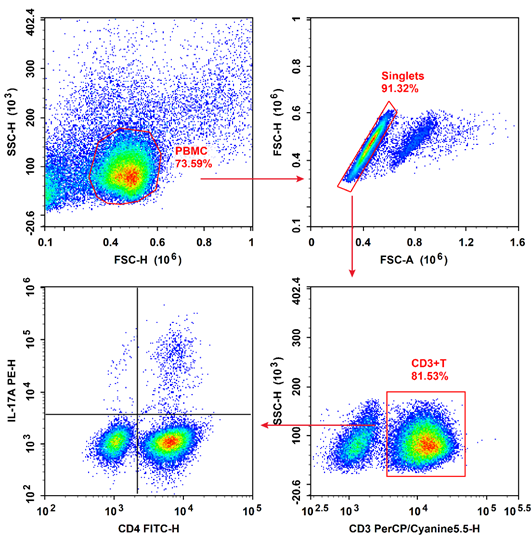

Then, CD4+ T cells implicated in neurological diseases can be further subclassified into four distinct phenotypes, each exerting specialized functional roles. Upon crossing the BBB, CD4+ helper T cells differentiate into T helper 1 (Th1) cells in an IL-12-dominant microenvironment; this differentiation drives central nervous system (CNS) inflammation and neuronal injury. Th17 cells represent another pro-inflammatory subset, whose differentiation is mediated by IL-23: these cells contribute to intestinal immunity and autoimmune pathogenesis, and have been linked to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration via activation of the Fas/FasL apoptotic pathway. By contrast, Th2 cell differentiation occurs in an IL-4-rich microenvironment,this subset orchestrates immune responses against helminths and mediates allergic reactions, while also attenuating neuroinflammatory processes[5]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress the effector functions of other Th cell subsets, maintaining peripheral tolerance to self-antigens and limiting inflammatory responses to exogenous antigens. Within the CNS, Tregs mitigate neuroinflammation and thereby protect against neurodegeneration[6].

Fig. 2 Flow cytometry analysis of Th17 cells in human peripheral blood.

Fig. 3 Flow cytometry analysis of Th1 and Th2 cells in human peripheral blood.

04 The role of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in maintaining neural homeostasis

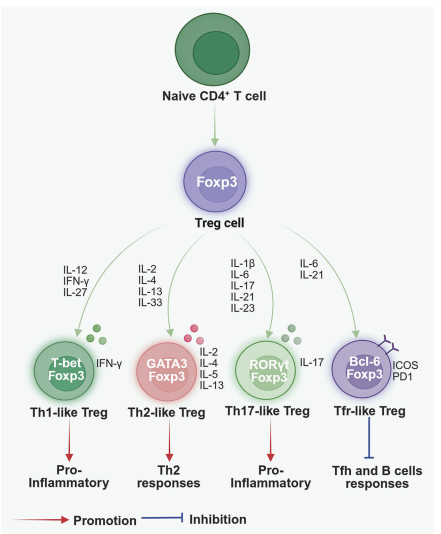

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a special subpopulation of immunosuppressive T cells that are essen

tial for sustaining immune homeostasis. They maintain self-tolerance, inhibit autoimmunity, and

act as critical negative regulators of inflammation in various pathological states including autoimmunity, injury, and degeneration of the nervous system[8].Characterized by their immunosuppressive capabilities and reliance on the transcription factor Foxp3 (Forkhead box protein P3), Tregs employ multiple mechanisms, including cytokine secretion, metabolic control, and cell contact inhibition, to restrain excessive immune activation to prevent autoimmunity while maintaining tissue repair processes[9].

4.1 Suppression of Pathological Neuroinflammation

Under conditions of nervous system injury or disease, immune cells are prone to overactivation and excessive release of inflammatory mediators, thereby triggering neuroinflammation. Regulatory T (Treg) cells exert a pivotal inhibitory role in this process: they can directly suppress the activation of immune effector cells (e.g., macrophages and dendritic cells) via secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Additionally, Treg cells can abrogate inflammatory signal transduction through contact-dependent mechanisms including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) signaling pathways thereby preventing inflammatory spread and subsequent neuronal damage.

4.2 Facilitation of Neural Tissue Repair and Regeneration

Following nerve injury, Treg cells recruit neural stem cells (NSCs) and drive their differentiation into mature neurons. Concurrently, by modulating the post-injury microenvironment, Treg cells reduce scar tissue formation, thereby establishing a permissive niche for axonal regeneration. For example, in spinal cord injury (SCI) models, enrichment of Treg cells has been shown to significantly enhance neurological function recovery.

4.3 Preservation of CNS Immune Privilege

The central nervous system (CNS) exhibits a state of “immune privilege,” characterized by tight regulation of immune responses. Regulatory T (Treg) cells preserve this privileged state by eliminating aberrant immune cells that infiltrate the CNS and suppressing autoreactive T cell-mediated attacks on neural tissues, thereby preventing the development of autoimmune neurological disorders such as MS.

Fig. 4 Treg cell plasticity[9].

05 Role of T cells in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis

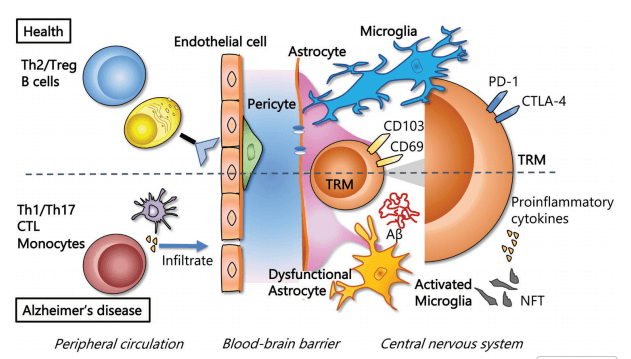

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory decline and cognitive impairment, linked to hallmark protein aggregates: amyloids in the brain (specifically amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques formed by abnormal deposition of amyloid protein in brain) and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein.. Immune cells play a critical role in AD pathogenesis; while the precise functions of T cells in AD remain controversial, studies demonstrate that T cell deficiency correlates with exacerbated AD pathology, whereas T cell transplantation mitigates pathological features. A key mechanism underlying T cell-mediated modulation of AD involves their regulation of humoral immunity: CD4+ T cells are essential for activating B cells to secrete antibodies and mediate humoral immune responses . In the context of AD, Aβ-specific T cells support the generation of B cells that produce anti-Aβ antibodies (Abs), which can neutralize Aβ toxicity and/or enhance macrophage-mediated Aβ uptake and degradation.T cells additionally activate macrophages to phagocytose misfolded proteins, including Aβ and Tau. Recent evidence indicates that animal models of AD exhibit impairment of the thymic microenvironment,particularly dysfunction of thymic epithelial cells (TECs),leading to reduced T cell numbers, a deficit that contributes to the progression of AD pathology. Consequently, strategies targeting T cell regeneration, such as thymic microenvironment rejuvenation, hold therapeutic potential for the treatment of AD[7].

Fig. 5 T-cells in healthy tissue and tissue of patients with Alzheimer's disease[4].

06 Research advancements in targeting T cells for neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative hallmarks can be indirectly ameliorated by modulating tissue homeostasis or abrogating maladaptive processes,including excessive microglial activation,wherein the migration of specifically engineered regulatory T cells may facilitate the restoration of tissue homeostasis. A further characteristic of neurodegenerative cascades is the accumulation of cells exhibiting a senescent phenotype; these senescent cells drive tissue dysfunction via their secretory products. In animal models, inducible transgene-based strategies targeting senescent cell elimination have been shown to delay age-associated pathologies. Analogously, car t cell therapy (senolytic cytotoxic CAR T cells directed against age-associated antigens [e.g., urokinase plasminogen activator receptor [uPAR] or natural killer group 2 member D ligand [NKG2DL]]) have demonstrated comparable efficacy. Notably, in post-mitotic neuronal populations, clearance of senescent cells represents a promising strategy to disrupt the self-sustaining cycle of neurodegeneration. However, minimizing neurotoxic side effects of car t cell treatment in this context poses a unique challenge, as remaining neurons,already depleted by pre-existing degeneration and lacking regenerative capacity,require maximal protection.. Leveraging their antigen-dependent migration properties, CAR T cells hold therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative disorders with localized pathology (e.g., Parkinson’s disease), where their focal accumulation could exert disease-modifying effects while sparing unaffected CNS regions, thereby mitigating off-target side effects [10].

In summary, T cells play a crucial, context-dependent role in neuroimmunology. They act as key mediators of immune-nervous system crosstalk and critical regulators of neural homeostasis and disease progression, with distinct operational mechanisms in the brain, spleen, lymph nodes, and vascular compartments. Furthermore, T cell-targeted interventions including engineered regulatory T (Treg) cells and senescent cytotoxic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells hold substantial therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases, although minimizing neurotoxic side effects remains a core challenge. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of T cell biology in the context of neuroimmunology, as well as their multifaceted roles in neurological disorders, provides a vital theoretical foundation for the development of novel T cell-targeted therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products

Table 1. Research Tools for T Cells

|

Cat. No. |

Product Name |

|

E-AB-F1001J |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD3 Antibody[OKT-3] |

|

E-AB-F1352L |

Elab Fluor® 488 Anti-Human CD4 Antibody[SK3] |

|

E-AB-F1196E |

APC Anti-Human IFN-γ Antibody[B27] |

|

E-AB-F1203D |

PE Anti-Human IL-4 Antibody[MP4-25D2] |

|

E-AB-F1173D |

PE Anti-Human IL-17A Antibody[BL168] |

|

E-CK-A091 |

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

|

E-CK-A103 |

Human PBMC Separation Solution(P 1.077) |

|

E-CK-A109 |

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

|

XJH001 |

Human Th1/Th2 Flow Cytometry Staining Kit |

|

XJH002 |

Human Th17 Flow Cytometry Staining Kit |

|

E-AB-F1137Q |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD45 Antibody[HI30] |

|

E-AB-F1230S |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Human CD3 Antibody[UCHT1] |

|

E-AB-F1352C |

FITC Anti-Human CD4 Antibody[SK3] |

|

E-AB-F1110J |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD8a Antibody[OKT-8] |

|

E-AB-F1194D |

PE Anti-Human CD25 Antibody[BC96] |

|

E-AB-F1152E |

APC Anti-Human CD127/IL-7RA Antibody[A019D5] |

References:

[1] Leunig, A., Gianeselli, M., Russo, S.J.et al.Connection and communication between the nervous and immune systems.Nat Rev Immunol 25, 912–933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-025-01199-6

[2] Kipnis, J., Gadani, S. & Derecki, N. Pro-cognitive properties of T cells.Nat Rev Immunol 12, 663–669 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3280

[3] Sarah Mundt et al.Conventional DCs sample and present myelin antigens in the healthy CNS and allow parenchymal T cell entry to initiate neuroinflammation.Sci. Immunol.4,eaau8380(2019).

doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aau8380

[4] Giuliani, F., Goodyer, C. G., Antel, J. P., & Yong, V. W. (2003). Vulnerability of human neurons to T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. The Journal of Immunology, 171(1), 368-379.

[5] Solleiro-Villavicencio, H., & Rivas-Arancibia, S. (2018). Effect of chronic oxidative stress on neuroinflammatory response mediated by CD4+ T cells in neurodegenerative diseases.Frontiers in cellular neuroscience,12, 114.

[6] He, F., and Balling, R. (2013). The role of regulatory T cells in neurodegenerative diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 5, 153–180. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1187

[7] Zhao, J., Wang, X., He, Y., Xu, P., Lai, L., Chung, Y., & Pan, X. (2023). The role of T cells in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis.Critical Reviews™ in Immunology,43(6).

[8] Duffy, S. S., Keating, B. A., Perera, C. J., & Moalem‐Taylor, G. (2018). The role of regulatory T cells in nervous system pathologies.Journal of neuroscience research,96(6), 951-968.

[9] Wang, L., Liang, Y., Zhao, C., Ma, P., Zeng, S., Ju, D., ... & Shi, Y. (2025). Regulatory T cells in homeostasis and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential.Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy,10(1), 345.

[10] Pfeffer, L. K., Fischbach, F., Heesen, C., & Friese, M. A. (2025). Current state and perspectives of CAR T cell therapy in central nervous system diseases. Brain, 148(3), 723-736.