Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant capacity, plays a critical and dual role in breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment. ROS, including free radicals such as superoxide anion and hydroxyl radical, as well as non-radical molecules like hydrogen peroxide, are continually generated through cellular metabolic processes, notably mitochondrial respiration. While physiological ROS levels serve as key signaling molecules, their sustained elevation causes oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, thereby promoting carcinogenesis. Cancer cells often maintain higher basal ROS levels than normal cells, achieving a redox homeostasis that supports proliferation but also confers a latent vulnerability. This vulnerability provides the rationale for pro-oxidative anticancer therapies that selectively escalate oxidative stress in cancer cells beyond their tolerable threshold, disrupting redox balance to trigger cell death.

In this context, we outline the sources and consequences of oxidative stress in breast cancer, discuss its pivotal role in tumor progression and highlight emerging strategies that target this redox imbalance. The precise interplay between ROS generation and antioxidant defenses ultimately dictates cellular fate, establishing the modulation of oxidative stress as a significant frontier in oncology research and treatment development.

Table of Contents

1. How Does Oxidative Damage Contribute to Breast Cancer?

2. Oxidative Stress Markers in Breast Cancer Patients

3. Role of Inflammation Induced by Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer

4. Strategies for Measuring Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer Research

5. Dietary Antioxidants and Their Effect on Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer

01 How Does Oxidative Damage Contribute to Breast Cancer?

Oxidative damage to cells is a significant driver of breast cancer development and progression[1]. ROS inflict damage on fundamental cellular components, leading to genomic instability, altered gene expression, and dysfunctional signaling pathways. Notably, oxidative stress and DNA damage represent a core pathogenic link in breast cancer, as ROS chemically modify DNA bases, causing mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and an increased risk of carcinogenesis[2]. The well-established biomarker 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) reflects such oxidative DNA damage[3].

Beyond DNA, ROS elicit oxidative damage to proteins and lipids: lipid peroxidation compromises membrane structural integrity and biological function, while protein carbonylation alters protein conformational and functional properties, disrupting intracellular signaling cascades and inducing cancer cell apoptosis[3].Yet, oxidative stress exerts a complex, context-dependent role in tumorigenesis and progression. For instance, recent investigations into invasive ductal carcinomas have demonstrated that E-cadherin functions as a survival factor for disseminated cancer cells by suppressing ROS-mediated apoptosis, thereby facilitating metastatic progression. This finding uncovers a key vulnerability in metastatic cancer cells and indicates that targeted inhibition of this E-cadherin-dependent survival pathway represents a promising therapeutic strategy for metastatic malignancies[4].

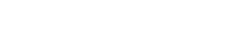

Conversely, chronic oxidative stress also promotes aggressive phenotypes, such as estrogen-independent growth in estrogen receptor positive cells, a hallmark of advanced disease[1].Elevated ROS in the tumor microenvironment (TME) suppresses immune function, fosters a mutagenic milieu, and accelerates tumor progression and therapy resistance. This dual role of ROS, involving direct cancer cell toxicity versus immune suppression, poses a therapeutic challenge[1]. Psychological stress has been shown to accelerate breast cancer progression via enhanced macrophage phospholipid peroxidation in the TME, mediated by ALOX15 and PEBP1[5]. Persistent free radicals from oxidative stress trigger chronic breast inflammation, characterized by elevated TNF-α from infiltrating macrophages, dysregulated IL-6, and upregulated COX2, factors correlating with poor prognosis, reduced drug response, and increased metastasis[6].

Fig. 1 ROS-mediated signaling in promotion of breast tumor growth, metastasis, angiogenesis, and drug resistance[1]. This diagram summarizes how ROS from stromal cells (CAFs and TAMs) in the tumor microenvironment activates key pathways like MAPK, PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, and HIF-1α, upregulating MMPs, VEGF, and growth factors to drive breast cancer progression, metastasis, angiogenesis, and drug resistance.

02 Oxidative Stress Markers in Breast Cancer Patients

Breast cancer progression is closely associated with disrupted redox homeostasis, characterized by elevated oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant capacity. Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate significant alterations in oxidative stress markers across different disease stages, highlighting their pathogenic and prognostic potential.

Key markers include:

8-OHdG: A recognized biomarker of oxidative DNA damage. Elevated levels are observed in breast cancer patients, indicating significant DNA injury[3].

Malondialdehyde (MDA): A primary product of lipid peroxidation. MDA levels are significantly elevated in breast cancer patients compared to healthy controls and correlate with disease progression[7].

Protein Carbonyls (PC): Reflect oxidative protein modification. Elevated PC levels distinguish malignant cases from benign or healthy subjects and correlate with tumor aggressiveness.

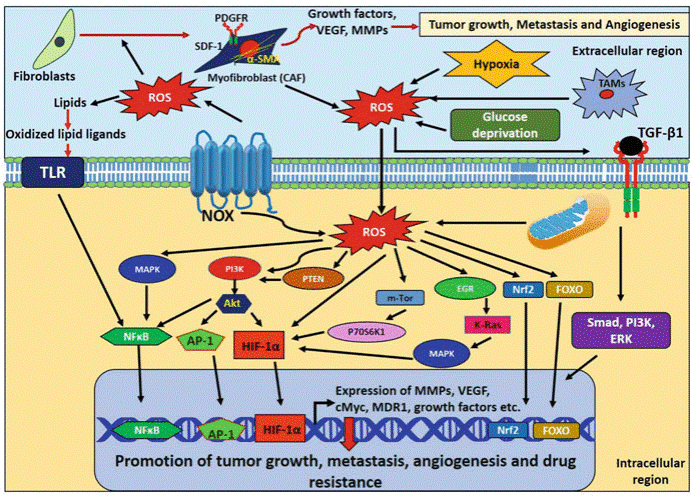

Total Antioxidant Status (TAS) and Total Oxidant Status (TOS): These parameters provide a comprehensive overview of systemic redox balance. An increased oxidative stress index (OSI), calculated as TOS/TAS, indicates significant oxidative stress. Studies report lower TAS and higher TOS and OSI in patients compared to healthy individuals[8].

Reduced Glutathione (GSH): A major endogenous antioxidant. Its depletion, or a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio, indicates increased oxidative stress and disrupted cellular redox status.

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD): A key antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals. Changes in SOD activity are influenced by disease stage, physical activity, and treatments, and its role can be dichotomous, acting as both a tumor suppressor and promoter depending on context.

Trace Elements: Deficiencies in elements like zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu), critical for enzymatic antioxidant activity, are common in malignancies and contribute to oxidative stress[9].

These markers can be influenced by factors such as age, disease stage, and chemotherapy. For instance, chemotherapy regimens like Adriamycin and Cyclophosphamide (AC) have been shown to increase oxidative stress markers in patients.

03 Role of Inflammation Induced by Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer

Oxidative stress and inflammation form a self-perpetuating cycle that drives breast cancer progression. ROS activate key signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, leading to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β[10, 11]. This inflammatory response further amplifies oxidative stress, resulting in sustained DNA damage, genomic instability, and tumor progression[11, 12].

Clinical studies demonstrate a positive correlation between the severity of oxidative stress and disease stage in breast cancer, particularly in aggressive subtypes like inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). In IBC, tumor cells obstruct dermal lymphatics, leading to rapid erythema, edema, and peau d'orange appearance, which are exacerbated by oxidative stress-driven pathways[13]. The compromised antioxidant defense system induces a pronounced inflammatory response, evidenced by elevated adenosine deaminase (ADA) activity and pro-inflammatory cytokines[7]. This oxidative imbalance is strongly associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and poorer prognosis in IBC, where cytokine cascades promote lymphangiogenesis and metastatic spread.

In post-menopausal women, obesity further amplifies oxidative stress and inflammation, creating a tumor-promoting microenvironment. For estrogen-receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, which includes a subset of IBC cases, higher BMI and leptin levels correlate with elevated ROS and pro-inflammatory signaling, predictive of larger tumor size, nodal involvement, and metastatic risk[14]. Notably, IBC is more prevalent in obese women, and adipose-derived cytokines may accelerate disease progression by reinforcing oxidative-inflammatory crosstalk.

In summary, the crosstalk between oxidative stress and inflammation is a hallmark of breast cancer progression, underpinning therapy resistance and aggressive phenotypes. In IBC, this vicious cycle is especially pronounced, fueling DNA damage, cytokine activation, and metabolic dysregulation. Targeting these interconnected pathways may offer novel therapeutic strategies for high-risk cases.

04 Strategies for Measuring Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer Research

Accurate assessment of oxidative stress is essential for understanding breast cancer progression and treatment response. Evaluation employs a range of complementary methodologies to quantify ROS, antioxidant capacity, and oxidative damage markers.

Biochemical Assays: Spectrophotometric methods are widely used to measure lipid peroxidation products like MDA and antioxidant enzymes such as SOD. The TOS and TAS provide integrated indices of systemic redox balance.

Immunological Techniques: ELISA offers high specificity for detecting oxidative damage products, such as 8-OHdG for DNA damage and protein carbonyls for protein oxidation.

Electrochemical Measurements: Advanced techniques like micrometer-sized electrodes coated with Pt black and platinized Pt nanoelectrodes are used for direct electrochemical detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in both non-transformed and metastatic human breast cells[15]. This allows for precise, localized measurements of ROS production.

Gene Expression Analysis: Techniques like real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) are used to measure the mRNA expression of genes related to oxidative stress and inflammation, such as COX-2, IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α[16].

The choice of methodology depends on the research objective. Immunohistochemistry is suitable for spatial localization in tissues, electrochemical sensors for dynamic ROS fluxes, and integrated indices like OSI for evaluating systemic oxidative stress. A strategic combination provides a comprehensive profile of the redox state in breast cancer.

Fig. 2 Detection Results of TOS in human serum, mouse serum, 10% rat heart tissue homogenate (the concentration of protein is 8.42 gprot/L), and 10% rat kidney tissue homogenate (the concentration of protein is 11.71 gprot/L) (The datas are provided by Elabscience.)

05 Dietary Antioxidants and Their Effect on Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer

Dietary antioxidants play a significant role in modulating oxidative stress in breast cancer, influencing both disease risk and progression, and their use is a key consideration in antioxidant therapy[17]. These compounds, derived primarily from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other plant-based foods, function by neutralizing ROS, reducing oxidative damage to cellular components, and interacting with key molecular pathways involved in carcinogenesis. However, their effects can vary considerably based on source, dosage, timing, and individual patient factors, and the effectiveness of antioxidants in cancer prophylaxis remains contentious, with research exhibiting variable outcomes.

5.1 Sources and Types of Dietary Antioxidants

Dietary antioxidants encompass a wide range of compounds, including:

Vitamins: Such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid), vitamin E (tocopherols and tocotrienols), and vitamin A. These vitamins act as direct free radical scavengers, helping to protect lipids, proteins, and DNA from oxidative damage.

Polyphenols: Found abundantly in foods like berries, green tea, cruciferous vegetables, and legumes. These compounds not only possess direct antioxidant activity but also modulate signaling pathways related to inflammation and cell survival[17].

Other Phytonutrients:Including key bioactive phytochemicals such as curcumin, resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and quercetin, alongside additional bioactive compounds from diverse plant extracts, all of which have been demonstrated to selectively inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation via oxidative stress-dependent mechanisms[18].

The total Dietary Antioxidant Capacity (DaC) is a concept that reflects the cumulative antioxidant power of an individual's diet. Higher DaC, achieved through a diverse intake of antioxidant-rich foods, has been associated with reduced levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in women undergoing adjuvant treatment for breast cancer[17].

5.2 Mechanisms of Action

The protective effects of dietary antioxidants against oxidative stress in breast cancer are mediated through multiple mechanisms.

Table 1. Dietary Antioxidants: Primary Sources and Proposed Mechanisms[19]

|

Antioxidant |

Primary Dietary Sources |

Proposed Mechanisms |

|

Vitamin C |

Citrus fruits, berries, tomatoes |

Direct ROS scavenging; NRF2-mediated induction of DNA repair enzymes (OGG1)[20] |

|

Vitamin E |

Nuts, seeds, vegetable oils |

Protection of cell membranes from lipid peroxidation |

|

Carotenoids |

Carrots, sweet potatoes |

Scavenging free radicals; potential role in enhancing immune surveillance |

|

Polyphenols |

Green tea, berries |

Scavenging ROS; anti-inflammatory effects; inhibition of pro-metastatic factors[18] |

In conclusion, dietary antioxidants, when consumed as part of a diverse and balanced diet, appear to play a beneficial role in mitigating oxidative stress in breast cancer. Their effects are mediated through a complex interplay of direct antioxidant action and modulation of cellular defense pathways. However, the role of antioxidants is complex, as they might interfere with the pro-oxidant mechanisms of some chemotherapies. Future research should continue to clarify the distinctions between food sources and supplements, and strive to develop personalized nutritional strategies.

Quick Overview of Popular Products

Table 2. Oxidative Stress Assay Kits

|

Cat. No. |

Product Name |

|

E-BC-K020-M |

Total Superoxide Dismutase (T-SOD) Activity Assay Kit (WST-1 Method) |

|

E-BC-K025-M |

Malondialdehyde (MDA) Colorimetric Assay Kit (TBA Method) |

|

E-EL-0060 |

MDA(Malondialdehyde) ELISA Kit |

|

E-BC-F005 |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Red) |

|

E-BC-K030-M |

Reduced Glutathione (GSH) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K117-M |

Protein Carbonyl Colorimetric Assay Kit (Tissue and Serum Samples) |

|

E-BC-K138-F |

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Fluorometric Assay Kit (Green) |

|

E-BC-K802-M |

Total Oxidant Status (TOS) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K801-M |

Total Antioxidant Status (TAS) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K033-M |

Vitamin E (VE) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K034-M |

Vitamin C (VC) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K284-M |

Plant Flavonoids Colorimetric Assay Kit |

|

E-EL-0028 |

8-OHdG (8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine) ELISA Kit |

|

E-EL-0128 |

4-HNE (4-Hydroxynonenal) ELISA Kit |

|

E-BC-K219-M |

Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC) Colorimetric Assay Kit (ABTS, Enzyme Method) |

|

E-BC-K225-M |

Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC) Colorimetric Assay Kit (FRAP Method) |

|

E-BC-K097-M |

Total Glutathione (T-GSH)/Oxidized Glutathione (GSSG) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

References:

[1] Radharani, N., et al., Oxidative Stress A Key Regulator of Breast Cancer Progression and Drug Resistance, in Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer. 2021.

[2] Kang, D.-H., Oxidative Stress, DNA Damage, and Breast Cancer. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 2002. 13(4): p. 540-549.

[3] Yahia, S., et al., Expression Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and Protein Carbonyl in Breast Cancer and Their Associations with Certain Immunological and Tumor Markers. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2025. 26(2): p. 639-646.

[4] Padmanaban, V., et al., E-cadherin Is Required for Metastasis in Multiple Models of Breast Cancer. Nature, 2019. 573(7774): p. 439-444.

[5] Luo, X., et al., Mitigating Phospholipid Peroxidation of Macrophages in Stress-induced Tumor Microenvironment by Natural ALOX15/PEBP1 Complex Inhibitors. Phytomedicine, 2024. 128: p. 155475.

[6] Devi, G.R., et al., The Role of Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer, in Cancer. 2014, Elsevier. p. 3-14.

[7] Ghafoor, D.D., Correlation Between Oxidative Stress Markers and Cytokines in Different Stages of Breast Cancer. Cytokine, 2023. 161: p. 156082.

[8] Feng, J.-F., et al., Serum Total Oxidant/Antioxidant Status and Trace Element Levels in Breast Cancer Patients. International Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2011. 17(6): p. 575-583.

[9] Barartabar, Z., et al., Assessment of Tissue Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Parameters, and Zinc and Copper Levels in Patients with Breast Cancer. Biological Trace Element Research, 2022. 201(7): p. 3233-3244.

[10] Sorriento, D., Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cancer. Antioxidants, 2024. 13(11): p. 1403.

[11] Dharshini, L.C.P., et al., Regulatory Components of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation and Their Complex Interplay in Carcinogenesis. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2023. 195(5): p. 2893-2916.

[12] Bel'skaya, L.V. and E.I. Dyachenko, Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer: A Biochemical Map of Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Current Issues in Molecular Biologyl, 2024. 46(5): p. 4646-4687.

[13] Woodward, W.A., Inflammatory Breast Cancer: Unique Biological and Therapeutic Considerations. The Lancet Oncology, 2015. 16(15): p. e568-e576.

[14] Yeon, J.-Y., et al., Evaluation of Dietary Factors in Relation to the Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Breast Cancer Risk. Nutrition, 2011. 27(9): p. 912-918.

[15] Li, Y., et al., Direct Electrochemical Measurements of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in Nontransformed and Metastatic Human Breast Cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2017. 139(37): p. 13055-13062.

[16] Roque, A.T., et al., Inflammation-induced Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer Patients. Medical Oncology, 2015. 32(12).

[17] Reitz, L.K., et al., Dietary Antioxidant Capacity Promotes a Protective Effect against Exacerbated Oxidative Stress in Women Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer in a Prospective Study. Nutrients, 2021. 13(12): p. 4324.

[18] Ray, G. and S.A. Husain, Role of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Vitamins in Women with Breast Cancer. Clinical Biochemistry, 2001. 34(1): p. 71-76.

[19] Chen, Z., et al., The Application of Approaches in Detecting Ferroptosis. Heliyon, 2024. 10(1): p. e23507.

[20] Singh, B., et al., Antioxidant-mediated Up-regulation of OGG1 via NRF2 Induction Is Associated with Inhibition of Oxidative DNA Damage in Estrogen-induced Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer, 2013. 13: p. 253.