Breast cancer has emerged as the most prevalent malignancy among women globally, and it is associated with the highest mortality rate among female malignancies. Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined as a subtype that tests negative for the expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), with triple negative breast cancer survival rate closely linked to its aggressive biological features. This aggressive phenotype is characterized by poor differentiation, high invasiveness, an inherent tendency toward local and distant metastasis, unfavorable prognosis, and elevated recurrence rates[1].Gene expression profiling studies have demonstrated that immune markers, mesenchymal phenotypes, androgen receptors, stem cell markers, and core molecular markers are all closely correlated with TNBC pathogenesis and progression[2]. Based on transcriptomic analyses, TNBC can be further stratified into six distinct subtypes: basal like 1, basal like 2, mesenchymal stem cell like, immunomodulatory, mesenchymal, and luminal androgen receptor[3]. Beyond the extracellular matrix (ECM), a diverse array of immune and stromal components within the tumor microenvironment (TME) including tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), antigen presenting cells, and fibroblasts play pivotal roles in driving TNBC progression and metastasis, which also constitutes a key target for optimizing tnbc treatment. TNBC accounts for 15-20% of all breast cancer cases and is clinically associated with a younger age of onset, elevated mutational burden, and increased risks of recurrence and mortality[4].

This article reviews the immune system responses to TNBC, the comparative efficacy and characteristics of chemotherapy versus immunotherapy for TNBC, the clinical application and mechanism of immune checkpoint inhibitors in TNBC, the potential of lifestyle modifications to enhance immune responses against TNBC, and the latest research advances regarding immune responses to TNBC.

Table of Contents

1. Immune system reaction to triple negative breast cancer

2. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy for triple negative breast cancer

3. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for triple negative breast cancer

4. Can lifestyle changes improve immune response against triple negative breast cancer?

5. New research findings on immune response to triple negative breast cancer

01 Immune system reaction to triple negative breast cancer

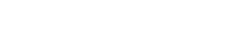

As a highly aggressive breast cancer subtype, TNBC possesses a distinct TME that differs significantly from other breast cancer subtypes; TNBC cells exploit distinct signaling cascades to reprogram the surrounding stromal and immune cells, thereby creating a pro tumorigenic microenvironment, and this pathological remodeling forms a detrimental positive feedback loop that not only accelerates tumor progression but also impairs the efficacy of tumor cell targeted therapies[5]. This unique TME is closely intertwined with the altered immune system responses to TNBC, a phenomenon that can be further elucidated by the cancer immunoediting hypothesis, which has emerged from decades of extensive investigations into carcinogenic mechanisms and the regulatory functions of the immune system[6] and is particularly governed by myeloid cells, which are critical effectors at all stages of tumor progression and orchestrate both innate and adaptive immune responses[7-9] (Fig 1). The immunoediting hypothesis delineates three sequential stages of tumorigenesis: elimination, equilibrium, and escape[6], with notable evidence indicating that a subset of TNBC cells may originate directly during the equilibrium or escape phases, bypassing the elimination stage entirely, while extrinsic factors are also known to perturb the transition dynamics between these phases[10]. In the elimination phase, the initial stage of cancer immunoediting, the innate and adaptive immune compartments collaborate synergistically to eradicate nascent TNBC cells; here, initial myeloid cells (iMCs),including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), initiate an inflammatory response to stimulate myelopoiesis and recruit additional immune cells to reinforce tumor cell elimination[7, 11-14]. When TNBC cells evade this immune mediated clearance, the disease advances to the equilibrium phase, where a dynamic stalemate is established between malignant cells and the immune system, with TNBC cells remaining subject to immune surveillance yet cannot be fully eliminated by immune effector cells[11]; notably, the failure of iMCs to fully eradicate TNBC cells triggers persistent inflammation, which in turn drives continuous recruitment of immune cells that are subsequently reprogrammed to facilitate tumor development[15-18]. In the subsequent escape phase, the immune system loses its capacity to constrain tumor growth, as cross talk between stromal components and TNBC cells fosters a highly immunosuppressive milieu that disrupts the tumor immune homeostasis and drives unchecked tumor progression[6]; this immunosuppressive TME is characterized by an accumulation of immature myeloid cells (MCs), including macrophages, DCs, neutrophils, monocytes, and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which exert distinct yet overlapping functions to promote TNBC progression.

Fig. 1 Composition of the tumor microenvironment[4].This figure delineates the diverse pro-tumor and anti-tumor mechanisms orchestrated by immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, encompassing cytokine secretion, T cell functional suppression, immune checkpoint activation, and associated metastatic processes.

02 Chemotherapy and immunotherapy for triple negative breast cancer

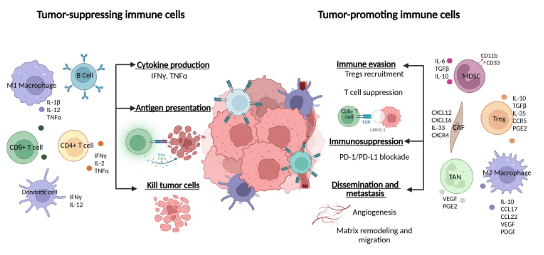

From the mechanistic perspective, chemotherapy and immunotherapy embody two fundamentally distinct paradigms for cancer treatment. Conventional chemotherapy regimens, such as those based on anthracyclines (e.g., epirubicin) and taxanes (e.g., paclitaxel),exert antitumor effects by directly targeting rapidly dividing cells[19]. Its core principle relies on non selective cytotoxicity, which not only eradicates malignant cells but also inflicts substantial damage on normal proliferative tissues (e.g., bone marrow and gastrointestinal mucosa), thereby triggering a spectrum of adverse reactions. In contrast, immunotherapy is centered on the concept of immune potentiation rather than direct cell killing. Specifically, immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting molecules such as programmed death receptor 1(PD-1)/programmed death receptor-ligand 1(PD-L1) abrogate tumor mediated suppression of T lymphocytes, which in turn reactivates the patient’s endogenous immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells[20]. A key advantage of this strategy is its potential to elicit sustained immune memory, a biological effect that enables continuous surveillance and clearance of recurrent tumor cells even after treatment cessation, thus offering the prospect of long term disease control and even curative outcomes[21]. Notably, these two therapeutic modalities are not mutually exclusive. Chemotherapy induced immunogenic cell death (ICD) can promote the release of tumor associated antigens, functioning as an in situ vaccine to reshape the TME (Fig. 2) into an immunostimulatory state[22]. This mechanistic synergy provides a robust theoretical rationale for the clinical application of chemoimmunotherapy combinations.

Fig. 2 The diagram of remodeling of the TME in TNBC immunotherapy[20]. This figure additionally incorporates the ERK/NF-κB pathway, PERK signaling, and GSDME-mediated cellular pyroptosis, alongside core molecules and pathways including MYC. It further delineates the global crosstalk between these components, thereby depicting a multi-target, multi-pathway synergistic regulatory network underlying the therapeutic effects of the agent in tumor treatment.

03 Immune checkpoint inhibitors for triple negative breast cancer

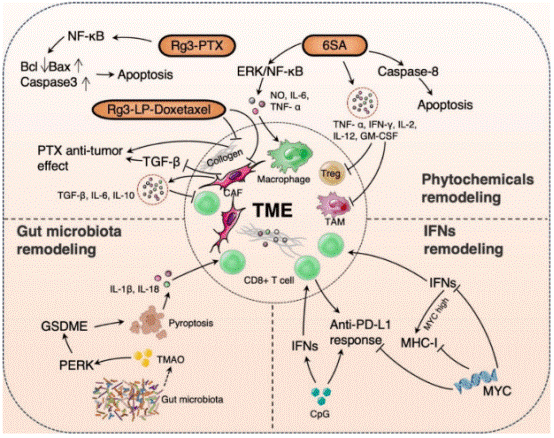

Tumors commonly evade immune surveillance via activating immune checkpoint mediated inhibitory pathways. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (Fig. 3), a class of agents that target pd 1 checkpoint inhibitor and related pathways, reverse these inhibitory signals to restore anti tumor immunity, as validated by extensive preclinical studies and clinical trials targeting CTLA-4, PD-1 or PD-L1[23]. In TNBC, ICI administration follows a clear stratification strategy based on disease stage and biomarkers, with tnbc pdl1 expression serving as a core determinant for treatment eligibility in advanced settings. For high risk early stage TNBC, the phase III KEYNOTE-522 trial confirmed that combining pembrolizumab with standard platinum taxane neoadjuvant chemotherapy (followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab maintenance post surgery) has become a new standard of care. This regimen markedly improves pathological complete response (pCR) rates and event free survival (EFS), with survival benefits observed regardless of tumor PD-L1 expression status[24, 25]. For metastatic or unresectable locally advanced TNBC, eligibility for immunotherapy hinges largely on PD-L1 expression, a validated biomarker. International guidelines recommend PD-L1 positivity (combined positive score [CPS] ≥ 10) as the first line ICI screening criterion. In this cohort, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy (e.g., albumin bound paclitaxel) significantly extend progression free survival (PFS) but fail to improve overall survival (OS)[26]. However, immunotherapeutic benefits (monotherapy or chemo combination) remain undefined in most PD-L1 negative or low expression (CPS < 10) patients.

Fig. 3 Immune checkpoint inhibitors[27].This figure delineates the crosstalk between tumor cells and immune cells, particularly T cells, and elucidates the mechanism of action underlying anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

04 Can lifestyle changes improve immune response against triple negative breast cancer?

Physical activity and weight loss/maintenance interventions are increasingly recognized as standard components of breast cancer survivorship care, with well documented beneficial impacts on patient outcomes. Recent large scale clinical trials have demonstrated that participation in exercise intervention programs confers significant improvements in physical fitness, life quality[28]. Combined interventions integrating caloric restriction with structured exercise, designed to mitigate obesity in TNBC patient population, have yielded moderate yet clinically meaningful weight loss effects[29]. While several of these studies have reported favorable alterations in inflammatory biomarkers[29], others have failed to detect such changes, implying that inflammation may serve as a mechanistic link bridging obesity, sedentary behavior, and the risk of cancer incidence or recurrence. For instance, regular moderate intensity aerobic exercise has been shown to reduce the levels of circulating inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) while enhancing the functions of natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which exhibit anti tumor activity. Notably, sedentary lifestyles have been independently associated with an elevated risk of breast cancer recurrence, and obesity specifically increases susceptibility to TNBC[30]. Collectively, these findings suggest that adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors, including regular physical activity and weight management, may reduce cancer recurrence risk, a critical consideration given the disproportionately high recurrence rate observed in TNBC.

05 New research findings on immune response to triple negative breast cancer

A pivotal recent discovery is that trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite derived from gut microbiota, can significantly enhance the infiltration and functional activity of CD8+ T cells in the TME. This effect not only effectively suppresses tumor growth but also improves the response rate to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors[31]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that the hyperactive glycolytic metabolism of TNBC cells depletes glucose in the TME and accumulates lactic acid, leading to local acidification and nutrient depletion. This metabolic perturbation impairs the metabolic adaptability and effector functions of T cells, which constitutes one of the critical mechanisms underlying ICI resistance[32]. Thus, the current focus of T cell mediated immunity research is centered on strategies to overcome TME induced suppression and enhance T cell activation and persistence. Meanwhile, the role of B cells antibody mediated immunity in TNBC is undergoing reevaluation. At tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) formed at the tumor margin or within the tumor tissue, B cells undergo activation, affinity maturation, and plasma cell differentiation. These processes enable the production of antibodies specific to tumor associated antigens (TAAs), which exert anti tumor effects through multiple mechanisms. First, via antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), these antibodies recruit effector cells such as NK cells to eliminate antibody coated tumor cells. Second, they directly lyse tumor cells through complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). Third, through opsonization, they promote the uptake and presentation of tumor antigens by antigen presenting cells (APCs), thereby indirectly activating T cell mediated immune responses.

In summary, this review synthesizes the immune responses to TNBC and the latest advances in its clinical management. TNBC harbors a unique TME, where immune crosstalk is orchestrated in line with the cancer immunoediting hypothesis, with myeloid cells serving as pivotal regulators. Chemotherapy exerts non selective cytotoxicity, while ICIs reactivate anti tumor immunity; these two modalities support the application of chemoimmunotherapy combinations by eliciting synergistic ICD. Clinically, the administration of ICIs is stratified by disease stage and PD-L1 expression status, yielding significant benefits in early stage TNBC and PD-L1 positive metastatic cases. However, unmet therapeutic needs persist for patients with low or negative PD-L1 expression. Lifestyle interventions have been shown to reduce the risk of TNBC recurrence by modulating inflammatory responses and immune function.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products

Table 1. Research Tools for breast cancer

|

Cat. No. |

Product Name |

|

E-CL-H1337 |

Human PGR (Progesterone Receptor) CLIA Kit |

|

E-EL-H6083 |

Human EGFR2(Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2) ELISA Kit |

|

E-EL-H6156 |

Human IL-6(Interleukin 6) ELISA Kit |

|

E-HSEL-H0003 |

High Sensitivity Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) ELISA Kit |

|

E-MSEL-H0025 |

Mini Sample Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) ELISA Kit |

|

E-OSEL-H0001 |

QuicKey Pro Human IL-6(Interleukin 6) ELISA Kit |

|

CQH001 |

CellaQuant™ Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) ELISA Kit |

|

ESP-H0009S |

Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) solid ELISPOT Kit |

|

E-EL-H0109 |

Human TNF-α(Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha) ELISA Kit |

|

ESP-H0010S |

Human TNF-α (Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha) solid ELISPOT Kit |

|

E-AB-F1129A |

Purified Anti-Human CD279/PD-1 Antibody[J116] |

|

E-AB-F1131D |

PE Anti-Mouse CD279/PD-1 Antibody[29F.1A12] |

|

E-AB-F1133A |

Purified Anti-Human CD274/PD-L1 Antibody[29E.2A3] |

|

E-AB-F1133C |

FITC Anti-Human CD274/PD-L1 Antibody[29E.2A3] |

|

MIH008N |

EasySort™ Human Naïve CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

|

MIH003N |

EasySort™ Human CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit |

|

MIH010N |

EasySort™ Human Memory CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

|

E-BC-F084 |

Glycolysis Stress Fluorometric Assay Kit |

|

E-BC-K044-M |

L-Lactic Acid (LA) Colorimetric Assay Kit |

References:

[1] Park, S.-Y., J.-H. Choi, and J.-S. Nam, Targeting cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers, 2019. 11(7): p. 965.

[2] Bianchini, G., et al., Treatment landscape of triple-negative breast cancer—expanded options, evolving needs. Nature reviews Clinical oncology, 2022. 19(2): p. 91-113.

[3] Jiang, Y.-Z., et al., Genomic and transcriptomic landscape of triple-negative breast cancers: subtypes and treatment strategies. Cancer cell, 2019. 35(3): p. 428-440. e5.

[4] Serrano García, L., et al., Patterns of immune evasion in triple-negative breast cancer and new potential therapeutic targets: a review. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024. Volume 15 - 2024.

[5] Yu, T. and G. Di, Role of tumor microenvironment in triple-negative breast cancer and its prognostic significance. Chinese Journal of Cancer Research, 2017. 29(3): p. 237.

[6] Dunn, G.P., L.J. Old, and R.D. Schreiber, The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annual Reviews. Immunol., 2004. 22(1): p. 329-360.

[7] Güç, E. and J.W. Pollard, Redefining macrophage and neutrophil biology in the metastatic cascade. Immunity, 2021. 54(5): p. 885-902.

[8] Wculek, S.K., et al., Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2020. 20(1): p. 7-24.

[9] Robinson, A., et al., Monocyte regulation in homeostasis and malignancy. Trends in Immunology, 2021. 42(2): p. 104-119.

[10] Schreiber, R.D., L.J. Old, and M.J. Smyth, Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science, 2011. 331(6024): p. 1565-1570.

[11] Dunn, G.P., et al., Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nature immunology, 2002. 3(11): p. 991-998.

[12] Burnet, F., The concept of immunological surveillance. Progress in experimental tumor research, 1970. 13: p. 1-27.

[13] Coussens, L.M. and Z. Werb, Inflammation and cancer. Nature, 2002. 420(6917): p. 860-867.

[14] Balkwill, F. and A. Mantovani, Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? The lancet, 2001. 357(9255): p. 539-545.

[15] Engblom, C., C. Pfirschke, and M.J. Pittet, The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2016. 16(7): p. 447-462.

[16] Cassetta, L., et al., Human tumor-associated macrophage and monocyte transcriptional landscapes reveal cancer-specific reprogramming, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Cancer cell, 2019. 35(4): p. 588-602. e10.

[17] Broz, M.L. and M.F. Krummel, The emerging understanding of myeloid cells as partners and targets in tumor rejection. Cancer immunology research, 2015. 3(4): p. 313-319.

[18] Gabrilovich, D.I., S. Ostrand-Rosenberg, and V. Bronte, Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2012. 12(4): p. 253-268.

[19] Galluzzi, L., et al., Immunological effects of conventional chemotherapy and targeted anticancer agents. Cancer cell, 2015. 28(6): p. 690-714.

[20] Liu, Y., et al., Advances in immunotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Molecular cancer, 2023. 22(1): p. 145.

[21] Gitto, S., et al., The emerging interplay between recirculating and tissue-resident memory T cells in cancer immunity: lessons learned from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy and remaining gaps. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021. 12: p. 755304.

[22] Wang, J., et al., Immunogenic cell death-based cancer vaccines: promising prospect in cancer therapy. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024. 15: p. 1389173.

[23] Heimes, A.-S. and M. Schmidt, Atezolizumab for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, Taylor & Francis Online 2019. 28(1): p. 1-5.

[24] Tiberi, E., et al., Immunotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncology and Therapy, 2025. 13(3): p. 547-575.

[25] Cortes, J., et al., Neoadjuvant immunotherapy and chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of high-risk, early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC cancer, 2023. 23(1): p. 792.

[26] Zhang, W., et al., A meta-analysis of application of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-based immunotherapy in unresectable locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Immunotherapy, 2023. 15(13): p. 1073-1088.

[27] Wesolowski, J., A. Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, and D. Pawlak, Modern Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers, 2022. 14(16): p. 3860.

[28] Hayes, S.C., et al., Exercise for health: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a pragmatic, translational exercise intervention on the quality of life, function and treatment-related side effects following breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment, 2013. 137(1): p. 175-186.

[29] Imayama, I., et al., Effects of a caloric restriction weight loss diet and exercise on inflammatory biomarkers in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer research, 2012. 72(9): p. 2314-2326.

[30] Kawai, M., et al., Height, body mass index (BMI), BMI change, and the risk of estrogen receptor‐positive, HER2‐positive, and triple‐negative breast cancer among women ages 20 to 44 years. Cancer, 2014. 120(10): p. 1548-1556.

[31] Wang, H., et al., The microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide promotes antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell metabolism, 2022. 34(4): p. 581-594. e8.

[32] Schreier, A., et al., Facts and Perspectives: Implications of tumor glycolysis on immunotherapy response in triple negative breast cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 2023. 12: p. 1061789.