T cells play a multifaceted and critical role in the immune response against breast cancer, acting both as direct anti-tumor effectors and as modulators within the complex tumor microenvironment (TME). This intricate involvement makes T cells a central focus in cancer immunotherapy strategies for breast cancer.

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the interplay between T cells and breast cancer. It outlines the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity, describes the functional heterogeneity of T cell subsets in breast cancer, and summarizes contemporary research on their bidirectional crosstalk with the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, it compares the efficacy and mechanisms of T cell-based therapies with conventional chemotherapy and highlights recent advances in T cell-targeted therapeutic strategies for breast cancer.

Table of Contents

1. How do T cells fight breast cancer?

2. Types of T cells involved in breast cancer treatment

3. Research on T cells and breast cancer

4. T cells vs. chemotherapy in breast cancer treatment

5. Latest advancements in T cell therapy for breast cancer

01 How do T cells fight breast cancer?

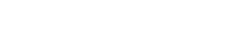

T cells combat breast cancer through a complex and multi-faceted immunological response, involving direct cytotoxic effects, modulation of the tumor microenvironment (TME), and participation in adaptive immune processes[1]. This intricate interplay highlights the crucial role of T cells in both natural anti-tumor immunity and as targets for immunotherapeutic interventions in breast cancer management[1].

The direct elimination of cancer cells by T cells is primarily mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), chiefly CD8+ T cells[2]. These lymphocytes recognize specific tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or neoantigens presented on the surface of cancer cells by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules. Following antigen recognition, activated CD8+ T cells induce programmed cell death in target cells through multiple distinct pathways[3].

Perforin and Granzyme Pathway: CD8+ T cells release perforin, a protein that creates pores in the cancer cell membrane, allowing granzymes (serine proteases) to enter the cell. Granzymes then activate caspases, leading to apoptosis[3].

Fas/Fas-ligand (FasL) Pathway: CD8+ T cells express FasL, which binds to Fas receptors on the surface of cancer cells, triggering an extrinsic apoptotic pathway[3].

Cytokine Production: CD8+ T cells can also secrete cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which can promote ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of programmed cell death in cancer cells. This pathway can enhance the anti-tumor effect, especially when combined with ferroptosis-inducing agents[3].

Beyond direct killing, helper T cells (Th cells), primarily CD4+ T cells, play a critical supportive role in orchestrating the overall immune response. They secrete various cytokines that enhance the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of other immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. CD4+ T cells also contribute to antigen presentation, processing tumor antigens via MHC class II molecules to further stimulate immune responses[4].

Fig. 1 Anti-tumor functions of T-cell subsets in breast cancer[1].

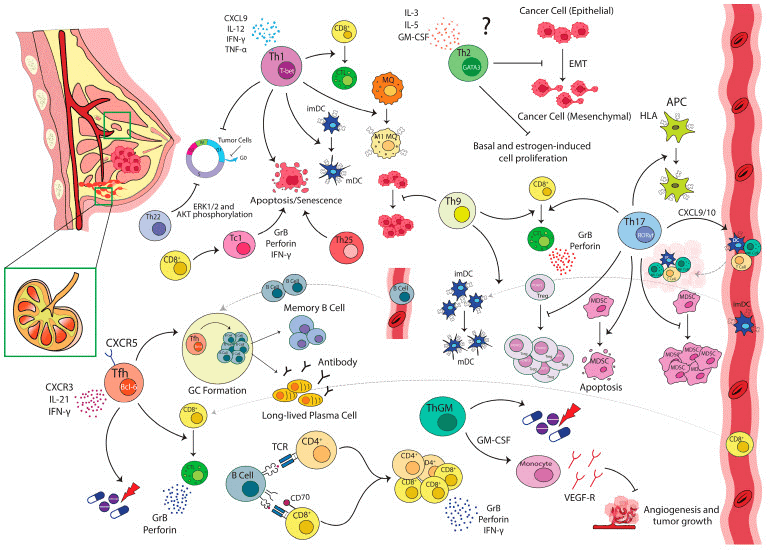

However, the efficacy of T cells in fighting breast cancer is often challenged by the immunosuppressive environment within the TME. This microenvironment, composed of cancer cells, stromal cells (like cancer-associated fibroblasts, CAFs), and various immune cells, can significantly hinder T cell function[5]. Key mechanisms of immunosuppression include:

T-cell Exhaustion: Prolonged antigen exposure and chronic inflammation in the TME can lead to T cells becoming “exhausted”, characterized by the loss of effector functions and the upregulation of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and CTLA-4[5].

Regulatory T cells (Tregs): These CD4+ T cell subsets suppress anti-tumor immunity by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10) and directly inhibiting effector T cell activity. A high infiltration of Tregs in breast cancer is often associated with poor prognosis[5,6].

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) and Macrophages: CAFs can recruit MDSCs and M2 macrophages, which contribute to an immunosuppressive milieu by inhibiting T cell proliferation and cytokine production[6].

Physical Barriers: Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) can remodel the extracellular matrix, creating a dense collagen-rich environment that physically impedes T cell infiltration into the tumor mass[6].

Fig. 2 Immunomodulatory mechanisms exerted by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)[6].

02 Types of T cells involved in breast cancer treatment

T cells are essential mediators of adaptive immunity in breast cancer, with distinct subsets fulfilling specialized roles in immune surveillance and therapy. Key populations involved include cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), helper T cells (Th cells), regulatory T cells (Tregs), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), and engineered T cells such as CAR-T and TCR-T cells, alongside specialized subsets like γδT cells. Each subset uniquely shapes the tumor immune microenvironment, thereby modulating disease progression and influencing therapeutic efficacy.

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ T cells, CTLs) serve as the primary effector cells for directly recognizing and eliminating breast cancer cells. They identify tumor-specific or tumor-associated antigens presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on the surface of breast cancer cells, and exert anti-tumor effects via three main mechanisms after activation. Specifically, CTLs release perforin to form pores in the cancer cell membrane, facilitating the entry of granzymes to activate caspases and trigger apoptosis.Forthermore, they express Fas ligand (FasL) that binds to Fas receptors on cancer cells to initiate the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Additionally, they secrete cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which induces iron-dependent ferroptosis in cancer cells, thereby enhancing anti-tumor efficacy, particularly when combined with ferroptosis-inducing agents[7].

Helper T cells (CD4+ T cells), or Th cells, do not directly kill cancer cells but are crucial for orchestrating the overall anti-tumor immune response. They secrete various cytokines that enhance the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of other immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. CD4+ T cells also play a role in antigen presentation, processing tumor antigens via MHC class II molecules to further stimulate immune responses[7].

Regulatory T cells (Tregs), a subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by the expression of FOXP3, are critical immunosuppressive cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME). They suppress anti-tumor immunity by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10), and by directly inhibiting the activity of effector T cells. High infiltration of Tregs in breast cancer is often associated with poor prognosis, as they contribute to immune evasion and tumor progression[8].

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) are a heterogeneous population of lymphocytes, including CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and B cells, that naturally infiltrate the tumor tissue. The presence and density of TILs are often correlated with patient prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapy, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). In TNBC, a higher infiltration of TILs is associated with better outcomes and increased responsiveness to immune checkpoint blockade therapies. TILs form the basis of adoptive cell therapy (ACT), where these naturally tumor-reactive cells are extracted from the patient’s tumor, expanded ex vivo to large numbers, and then reinfused into the patient to enhance anti-tumor immunity[9].

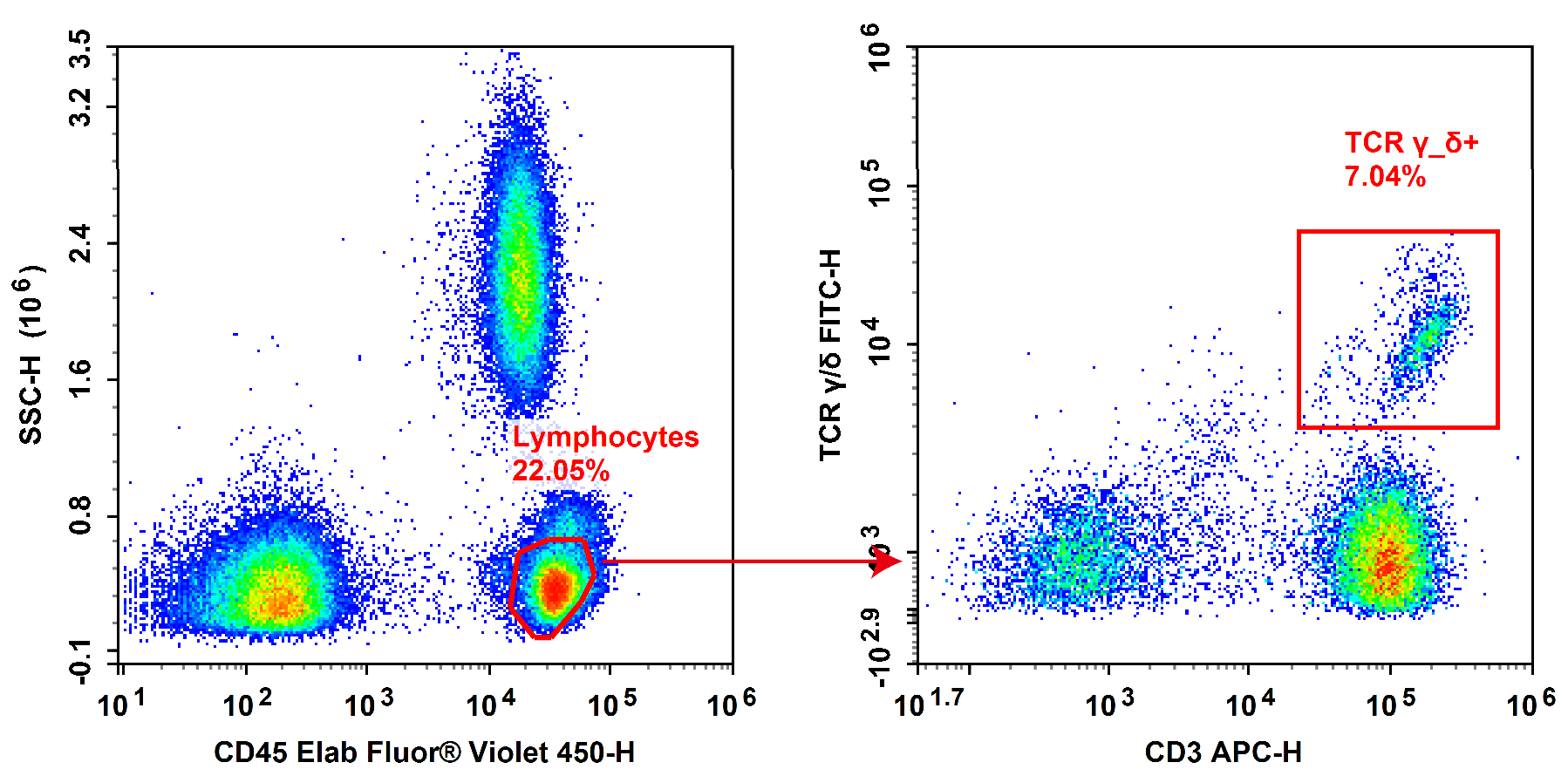

Gamma-Delta T cells (γδ T cells) are a unique subset of T lymphocytes that operate at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. A significant advantage of γδ T cells is their ability to directly identify and eliminate tumor cells without relying on HLA-antigen presentation, broadening their potential applicability to a wider range of patients. They can also exert potent anti-tumor effects and play a role in modulating other immune responses, making them a promising avenue for novel immunotherapeutic strategies[8,9].

The intricate interplay of these T cell types, along with other immune and stromal cells, determines the success of the immune response against breast cancer. Understanding their individual roles and collective functions is vital for developing effective, targeted immunotherapies.

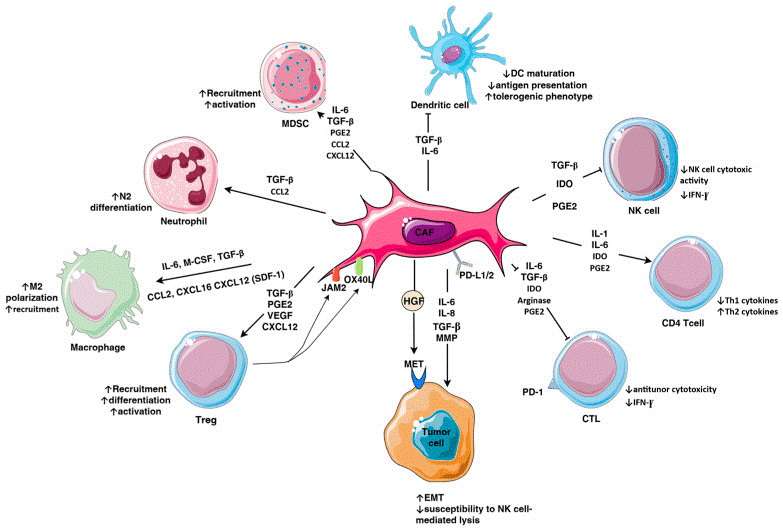

Fig. 3 Fresh 4T1 tumor tissues harvested from BALB/c mice were enzymatically digested using a dedicated tumor tissue dissociation solution to generate single-cell suspensions, and the relative proportions of T cells infiltrating the tumor tissues were subsequently stained with PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Mouse CD45, FITC Anti-Mouse CD3, PE Anti-Mouse CD4, APC Anti-Mouse CD8a, followed by analysis via flow cytometry. (The datas are provided by Elabceience)

Fig. 4 Normal human peripheral blood cells are stained with FITC Anti-Human TCRγ/δ, APC Anti-Human CD3 and Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD45, followed by analysis via flow cytometry. (The datas are provided by Elabceience)

%20in%20Human%20PBMCs.png)

Fig. 5 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Human CD45, Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Human CD3, FITC Anti-Human CD4, PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Human CD8, PE Anti-Human CD25 and APC Anti-Human CD127, followed by analysis via flow cytometry. Regulatory T cells (Treg cells) exhibit the phenotype of CD45+CD3+CD4+CD127LOW/-CD25+. (The datas are provided by Elabceience)

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table.1 Multicolor Panel for Flow Cytometric Analysis of T Cells

|

Marker |

Clone |

Fluorochrome |

Cat. No. |

Species Reactivity |

|

CD45 |

30-F11 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1136J |

Mouse |

|

CD3 |

17A2 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1013C |

Mouse |

|

CD4 |

GK1.5 |

PE |

E-AB-F1097D |

Mouse |

|

CD8a |

53-6.7 |

APC |

E-AB-F1104E |

Mouse |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Human |

|

CD3 |

OKT-3 |

APC |

E-AB-F1001E |

Human |

|

TCR γ/δ |

B1 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1145C |

Human |

|

CD45 |

HI30 |

Elab Fluor® Violet 450 |

E-AB-F1137Q |

Human |

|

CD3 |

UCHT1 |

Elab Fluor® Red 780 |

E-AB-F1230S |

Human |

|

CD4 |

SK3 |

FITC |

E-AB-F1352C |

Human |

|

CD8 |

OKT-8 |

PerCP/Cyanine5.5 |

E-AB-F1110J |

Human |

|

CD25 |

BC96 |

PE |

E-AB-F1194D |

Human |

|

CD127 |

A019D5 |

APC |

E-AB-F1152E |

Human |

03 Research on T cells and breast cancer

T cells are pivotal components of the immune system, playing a dual role in breast cancer (BC) by mediating both immune protection and, paradoxically, orchestrating tumor progression and metastasis. The interaction between T cells and breast cancer is complex, involving various T cell subsets that either suppress or promote tumor growth, and this understanding is critical for developing effective immunotherapeutic strategies.

Researches on T cells in the field of breast cancer focus on the pivotal role of T lymphocytes in orchestrating anti-tumor immune responses, as well as the development of T cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies. Key research areas include the functional characterization of endogenous T cell subsets: a primary focus is placed on cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes (CTLs), which eliminate breast cancer cells by recognizing tumor antigens presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and inducing target cell apoptosis, while CD4+ helper T cells promote the activation and persistence of CTLs through modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME)[9]. Another core research direction is to elucidate the mechanisms underlying T cell exhaustion in the immunosuppressive TME. For instance, chronic antigen stimulation and inhibitory signals (e.g., PD-1 and CTLA-4 pathways) can impair T cell effector functions, and related studies provide a theoretical rationale for immune checkpoint blockade therapies. In addition, extensive investigations have been carried out on engineered T cell therapies, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and T-cell receptor (TCR) T cells. For example, CAR-T cells recognize tumor antigens in an MHC-independent manner, and emerging targets such as Trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (Trop2) are driving its exploration in the field of breast cancer. In contrast, TCR-T cells exhibit unique potential in solid tumor therapy by targeting intracellular antigens that are inaccessible to CARs[10].

04 T cells vs. chemotherapy in breast cancer treatment

The comparison between T cell-based therapies and chemotherapy in breast cancer management is not a straightforward binary choice, instead, these two fundamentally distinct therapeutic modalities are increasingly deployed in combination. The key characteristics of the two strategies are summarized in the following table[10,11].

Table. 2 The key characteristics of T cell-based therapies vs. chemotherapy in breast cancer[10,11]

|

Aspect |

Chemotherapy |

T Cell-based Immunotherapies |

|

Core Principle |

Uses cytotoxic drugs to directly kill rapidly dividing cells (both cancerous and some healthy ones). |

Engages or engineers the patient's own immune system to specifically recognize and destroy cancer cells. |

|

Primary Mechanism |

Induces tumor cell death, sometimes in a way that can activate an immune response (e.g., immunogenic cell death). |

Includes checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1), CAR-T cells, and other methods to overcome tumor immune evasion and boost T cell attack. |

|

Role in Standard Care |

Foundation treatment for many stages and subtypes (e.g., neoadjuvant, adjuvant, metastatic). |

Established for specific cases (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors + chemo for some TNBC); others (like CAR-T) are investigational for breast cancer. |

|

Impact on Immune System |

Can suppress general immunity (e.g., reduces T helper cells). May also cause surviving tumor cells to activate immune defenses, creating a "whack-a-mole" problem for later immunotherapy. |

Specifically designed to activate and enhance anti-tumor immunity. |

|

Key Considerations |

Broad side effects (nausea, hair loss, immunosuppression). Effectiveness varies by subtype. |

Can cause unique side effects (e.g., cytokine release syndrome with CAR-T). Effectiveness is highly dependent on tumor immunogenicity and overcoming the tumor microenvironment. |

05 Latest advancements in T cell therapy for breast cancer

The landscape of cancer immunotherapy has significantly evolved, offering novel strategies that leverage the immune system to combat malignancies, including breast cancer (BC). Breast cancer, identified as the most frequently diagnosed cancer globally in 2023, surpassing lung, colon, and stomach cancers, underscores the critical need for advanced therapeutic interventions[11]. While traditional treatments like surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy remain foundational, immunotherapy, particularly T cell-based approaches, introduces a new paradigm by enhancing the patient's immune function to eliminate tumor cells[11].

One of the central challenges in cancer immunotherapy, especially for breast cancer, is the tumor's sophisticated ability to evade immune surveillance and suppression. This evasion often involves mechanisms such as masking tumor antigens or activating inhibitory pathways like programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which can lead to T cell exhaustion. T cell therapy aims to counteract these evasion mechanisms either by releasing immunological “brakes” through checkpoint blockade or by engineering immune cells for enhanced tumor targeting[12].

Breast cancer’s inherent heterogeneity, characterized by molecular subtypes such as Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-Enriched, and Basal-like (including triple-negative breast cancer, TNBC), complicates therapeutic approaches. Each subtype possesses distinct biological drivers and varying responses to therapy, necessitating personalized treatment strategies. TNBC, defined by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), has historically been difficult to treat with conventional targeted therapies. However, its genomic instability and high proliferative rates also render it susceptible to immunotherapeutic interventions, including T cell-based strategies[13].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a pivotal component of T cell-centric immunotherapy for breast cancer. These agents, typically antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, function by blocking the inhibitory signals emitted by cancer cells, thereby allowing T cells to maintain their effector functions and target the tumor effectively. The efficacy of ICIs is frequently enhanced when integrated with other therapeutic modalities in combination immunotherapy regimens. For instance, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) therapy can expand the pool of activated tumor-reactive T cells in lymph nodes, while anti-PD-1 therapy ensures these T cells remain functionally active at the tumor site, creating a synergistic anti-tumor effect[14].

Beyond ICIs, engineered T cell therapies are also advancing. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) represent a crucial element in engineering immunity against cancer. These cells, generated ex vivo from patient blood monocytes, act as potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs). They present tumor-associated antigens via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and provide co-stimulatory signals essential for activating T cells. Dendritic cell (DC) vaccines, which utilize these moDCs, are designed to prime a patient’s T cells to recognize and destroy tumors. The therapeutic potential of DC vaccines is further amplified when combined with checkpoint inhibitors, where the vaccine initiates the priming of tumor-specific T cells, and the checkpoint inhibitor subsequently sustains their effector function within the tumor microenvironment[14].

Another critical aspect influencing T cell response in breast cancer immunotherapy is immunogenic cell death (ICD). ICD is a regulated form of cell death that transforms dying tumor cells into an endogenous vaccine by releasing specific danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Many conventional cancer treatments, such as certain chemotherapeutic agents like anthracyclines and radiation therapy, can induce ICD. This process amplifies their therapeutic effect by recruiting and activating dendritic cells, which then present tumor antigens and promote a durable, tumor-specific T cell response. Combining ICD-inducing therapies with checkpoint inhibitors can further augment this effect, essentially turning the tumor itself into an “in situ” vaccine that stimulates systemic T cell immunity[15].

Identifying predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy response is essential, particularly for TNBC. The expression of PD-L1, quantified by a Combined Positive Score (CPS) of at least 10, has become a standard biomarker for guiding immunotherapy use in metastatic TNBC, integrating immunology, diagnostic pathology, and clinical decision-making. In early-stage breast cancer, immunotherapy can provide benefits across the patient population, irrespective of PD-L1 expression status. While the baseline presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is a significant prognostic indicator for a favorable response to chemotherapy, its precise predictive role for the additional benefit of immunotherapy is still under investigation[16].

The complexity of T cell therapy and other immunotherapeutic approaches also extends to the management of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These are mechanism-based toxicities that arise from a breakdown in self-tolerance, potentially affecting any organ system. Careful monitoring and interdisciplinary management are crucial to differentiate irAEs from other conditions and to apply appropriate treatment algorithms, ensuring patient safety and treatment efficacy[17].

In summary, recent advancements in T cell therapy for breast cancer encompass a multifaceted approach involving immune checkpoint inhibitors, dendritic cell vaccines, and strategies that harness immunogenic cell death. This integrated, multidisciplinary strategy, supported by ongoing advancements in biomarker identification and a deeper understanding of tumor immunology, offers renewed hope for improving outcomes for breast cancer patients.

Elabscience® Quick Overview of Popular Products:

Table. 3 Reagents for Breast Cancer Research

|

Product Name |

Cat. No. |

|

Human PBMC Separation Solution (P 1.077) |

E-CK-A103 |

|

Cell Stimulation and Protein Transport Inhibitor Kit |

E-CK-A091 |

|

Intracellular Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer Kit |

E-CK-A109 |

|

10×ACK Lysis Buffer |

E-CK-A105 |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM002N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD8+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM003N |

|

EasySort™ Mouse CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIM001N |

|

EasySort™ Human CD3+T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH001N |

|

EasySort™ Human CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH002N |

|

EasySort™ Human CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit |

MIH003N |

|

Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIH001A |

|

Mouse CD3/CD28 T Cell Activation Beads |

MIM001A |

|

Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit |

E-CK-A108 |

|

ATP Colorimetric Assay Kit (Enzyme Method) |

E-BC-K774-M |

|

ATP Chemiluminescence Assay Kit (Double Reagent) |

E-BC-F300 |

|

Human IFN-γ (Interferon Gamma) ELISPOT Kit |

ESP-H0002 |

|

Human IL-6 (Interleukin 6) solid ELISPOT Kit |

ESP-H0009S |

References:

[1] Zareinejad, M., Mehdipour, F., Roshan-Zamir, M., Faghih, Z., & Ghaderi, A. (2023). Dual functions of T lymphocytes in breast carcinoma: from immune protection to orchestrating tumor progression and metastasis. Cancers, 15(19), 4771. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194771.

[2] Hanahan, D., Michielin, O., & Pittet, M. J. (2024). Convergent inducers and effectors of T cell paralysis in the tumour microenvironment. Nature Reviews Cancer, 25(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-024-00761-z.

[3] Chamorro, D. F., Somes, L. K., & Hoyos, V. (2023). Engineered Adoptive T-Cell Therapies for Breast Cancer: Current Progress, Challenges, and Potential. Cancers, 16(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16010124.

[4] Li, R., & Cao, L. (2023). The role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer and the research progress of adoptive cell therapy. Frontiers in Immunology,14:1194020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1194020.

[5] Shao, W., Yao, Y., Yang, L., Li, X., Ge, T., Zheng, Y., Zhu, Q., Ge, S., Gu, X., Jia, R., Song, X., & Zhuang, A. (2024). Novel insights into TCR-T cell therapy in solid neoplasms: optimizing adoptive immunotherapy. Experimental Hematology & Oncology,13(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-024-00504-8.

[6] Vuletic, A., Mirjacic Martinovic, K., & Jurisic, V. (2025). The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Its Therapeutic Targeting. Cells, 14(17), 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14171353.

[7] Ham, B., Kim, S. Y., Kim, Y.-A., Han, D., Park, T., Cha, S., Jung, S., Kim, J. H., Park, G., Gong, G., Lee, H. J., & Shin, J. (2024). Persistence and enrichment of dominant T cell clonotypes in expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes of breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 131(1), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-024-02707-6.

[8] Yan, W., Dunmall, L. S. C., Lemoine, N. R., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Wang, P. (2023). The capability of heterogeneous γδ T cells in cancer treatment. Frontiers in Immunology, 14:1285801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1285801.

[9] Wang, X., Gao, H., Zeng, Y., & Chen, J. (2024). A Mendelian analysis of the relationships between immune cells and breast cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1341292.

[10] Chamorro, D. F., Somes, L. K., & Hoyos, V. (2023). Engineered adoptive T-Cell therapies for breast cancer: current progress, challenges, and potential. Cancers, 16(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16010124.

[11] Guo, Y., Zheng, G., Fan, Y., Li, L., & Sun, Y. (2025). Recent advances in immunotherapy for breast cancer. Discover Oncology, 16(1):1858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-025-03493-0.

[12] Jin, M., Fang, J., Peng, J., Wang, X., Xing, P., Jia, K., Hu, J., Wang, D., Ding, Y., Wang, X., Li, W., & Chen, Z. (2024). PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in breast cancer: research insights and sensitization strategies. Molecular Cancer, 23(1):266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-02176-8.

[13] Li, Y.-W., Dai, L.-J., Wu, X.-R., Zhao, S., Xu, Y.-Z., Jin, X., Xiao, Y., Wang, Y., Lin, C.-J., Zhou, Y.-F., Fu, T., Yang, W.-T., Li, M., Lv, H., Chen, S., Grigoriadis, A., Jiang, Y.-Z., Ma, D., & Shao, Z.-M. (2024). Molecular characterization and classification of HER2-Positive breast cancer inform tailored therapeutic strategies. Cancer Research, 84(21), 3669–3683. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-23-4066.

[14] Vranic, S., Cyprian, F. S., Gatalica, Z., & Palazzo, J. (2021). PD-L1 status in breast cancer: Current view and perspectives. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 72, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.003.

[15] Eteshola, E. O. U., Landa, K., Rempel, R. E., Naqvi, I. A., Hwang, E. S., Nair, S. K., & Sullenger, B. A. (2021). Breast cancer-derived DAMPs enhance cell invasion and metastasis, while nucleic acid scavengers mitigate these effects. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids, 26, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.06.016.

[16] Yu, Y., Jin, X., Zhu, X., Xu, Y., Si, W., & Zhao, J. (2023). PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Immunology, 14:1206689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1206689.

[17] Ramos-Casals, M., & Sisó-Almirall, A. (2024). Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Annals of Internal Medicine, 177(2), ITC17–ITC32. https://doi.org/10.7326/aitc202402200.